Lubomir Kavalek

Huffington Post, January 12, 2011New and Old Chess Champions

As we enter the new decade, the chess world is ruled by a middle-aged man and a teenage girl. A twenty-something phenom presides over the world's ratings and a new book recalling one of the greatest chess magicians has been published recently.

The Champions

Vishy Anand steps into the year 2011 as the world chess champion. At 41, the Indian grandmaster can look back on his career contentedly. In 1991 in Brussels, he almost eliminated Anatoly Karpov from the world championship cycle. In the next 20 years, Anand won many major tournaments and world championships under different formats and time controls. How long can Anand keep the world title is not clear, but I can't imagine him free-falling from the chess Olympus any time soon.

Vishy Anand steps into the year 2011 as the world chess champion. At 41, the Indian grandmaster can look back on his career contentedly. In 1991 in Brussels, he almost eliminated Anatoly Karpov from the world championship cycle. In the next 20 years, Anand won many major tournaments and world championships under different formats and time controls. How long can Anand keep the world title is not clear, but I can't imagine him free-falling from the chess Olympus any time soon.

Hou Yifan is the current women's world champion and at age 16, the youngest in chess history.

Discovered by the chess world at the age of 11, she was predicted to win the world title one day. Her confidence grew and at the age 12 the Chinese girl stated her plans as follows: buy real estate in Paris and overtake Judit Polgar, the all-time best woman. It may happen, but not yet. Polgar, who was rated among the world's top 10 in her prime, is rated 184 points above Hou -- a steep mountain to climb.

Her confidence grew and at the age 12 the Chinese girl stated her plans as follows: buy real estate in Paris and overtake Judit Polgar, the all-time best woman. It may happen, but not yet. Polgar, who was rated among the world's top 10 in her prime, is rated 184 points above Hou -- a steep mountain to climb.

In Fischer's footsteps

Anand has to wait for his next challenger for the world crown. He will come from the eight-player Candidates competition in May. It will not be the world's top rated Magnus Carlsen who decided to skip the current world qualification cycle. His move drew some criticism from other players and chess celebrities, but the Norwegian was merely being consistent. In December 2008, Carlsen and Mickey Adams withdrew from the World Cup, a series of six tournaments that were losing form and shape. FIDE changed the venues and the players even though it was a qualification for the next world championship.

Bobby Fischer made a similar move after the Soviet players cheated on him during the 1962 Candidates tournament. After FIDE changed the qualifying tournament to one-on-one Candidates matches, he showed up again at the 1967 Interzonal in Sousse, Tunisia. He played 10 games with us and left after a dispute with the organizers. Fischer returned in 1970, stronger than ever, and went all the way, becoming the world champion at the age of 29. Like Fischer, Carlsen has time, but his game has to keep maturing.

Last January, Carlsen fulfilled one of his dreams and became the world's top-rated player. A year later, the Norwegian grandmaster is still number one on the FIDE rating list with 2814 points, Anand is second with 2810 and third is the Armenian GM Levon Aronian with 2805 points. Aronian dominated the FIDE Grand Prix tournaments and for the last 18 months dwelled among the world's top five players. Last November in Moscow, he won the World Blitz championship and shared first place at the Tal Memorial, played in honor of one of the most fascinating world champions. You start talking about attacks, combinations and magic in chess and you ultimately end up talking about Misha Tal. It is inevitable.

On a magical journey with Misha Tal

Mikhail Tal (1936-1992) clinched the world title a half century ago, arriving with hurricane force. He won the 1957 Soviet championship and within three short years he became the world champion. It was a fast, reckless journey. Misha Tal was a free spirit. You gave him freedom and he would fly. It was a joy to watch him create his masterpieces, it was a great time to grow up in chess.

"You played like Tal," became one of the highest accolades for attackers. With his spectacular sacrifices and combinations, Tal won the hearts of chess fans and inspired many players. Plenty of them tried and failed to play like him. It was especially tempting to sacrifice pieces when Tal was present. At the 1961 European Team Championship in Oberhausen, Germany, Tal could only watch the incredible adventures of the young master Jindrich Trapl who in nine games sacrificed eight pawns, two exchanges, two light pieces and a queen. He was promptly called the Czech Tal and some wondered why the real Tal was not nicknamed the Latvian Trapl.

In today's computer-infested chess world the attacks of the late world champion Mikhail Tal are as remarkable as they were a half century ago. A fascinating book by Karsten Mueller and Raymund Stolze, " Zaubern wie Schachweltmeister Michail Tal," recently published in German by Edition Olms, re-lives the magical moments created by the Latvian grandmaster. Two years in the making, the book invites the reader to solve 100 positions from Tal's games. It is also loaded with tactical tips and memories of players who knew Tal well or played against him, such as Boris Spassky, Anatoly Karpov, Vladimir Kramnik, Robert Huebner and Artur Yusupov.

Tal had a great sense of humor. "There are two kinds of sacrifices," he said, for example. "The correct one and mine." His were spectacular and speculative. The book treats both kinds, adds warm-up combinations and ends with a chapter on how to correctly defend against the magician.

Most analyzed game

Huebner, one of the world's best defenders and analysts, wrote the longest piece for the book. He argues that Tal was not a pure tactician and his sacrifices were made with strategical goals in mind. Throughout his life, Tal did not write most of his articles and game comments. He usually dictated them. Incredible variations came from his head. But there was one game he skipped commenting on and it became the most analyzed game.

In his book "The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal," Misha provided only a diagram and the last 20 moves of his game against Dieter Keller from Zurich 1959, explaining that the variations left behind the scenes were numerous and complicated. "I did not want to give a faulty analysis, and to work through it to the end is, I am afraid , hardly possible," he said.

Of course, this was a challenge for Huebner. He wrote his first analysis of the Tal-Keller game 18 years ago. Some annotators, including Garry Kasparov, copied it with all of Huebner's mistakes. The new corrected and expanded version is 43 pages long. Before going deeply into the game, Huebner briefly points out the critical moments.

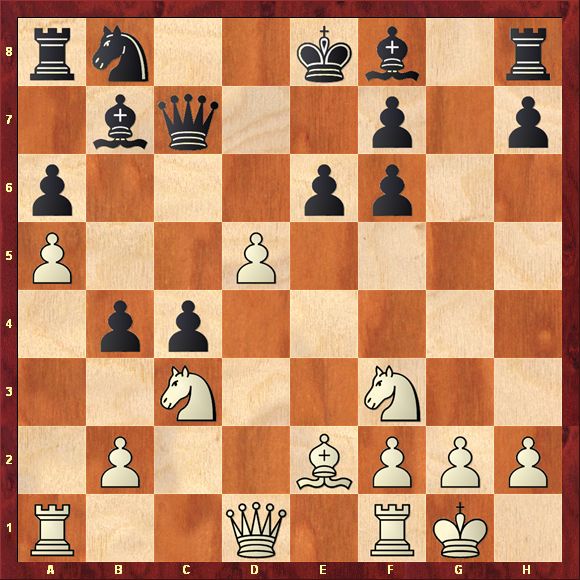

Tal - Keller

Zurich 1959

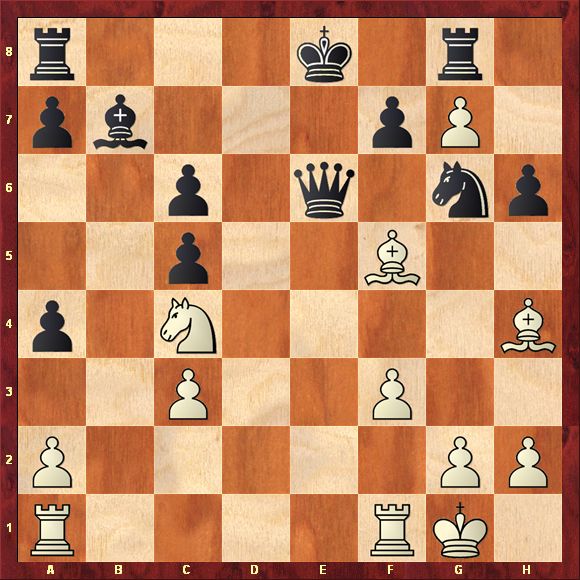

1.Nf3 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 d5 4.d4 c6 5.Bg5 dxc4 6.e4 b5 7.a4 Qb6 8.Bxf6 gxf6 9.Be2 a6 10.0-0 Bb7 11.d5 cxd5 12.exd5 b4? (Destroys the balance; white is winning.) 13.a5 Qc7

14.dxe6 bxc3 15.Nd4 Rg8 16.Qa4+ Kd8 17.g3 Bd5 18.Rfd1? (A mistake, giving away the advantage. 18.Rad1 was correct.) 18...Kc8? (A wrong reply, allowing white another winning possibility. After 18...cxb2 19.Rab1 c3 Huebner does not se how can white's attack break through.) 19.bxc3? (The chances are now equal. 19.Qe8+ Kb7 20.bxc3 was winning.) 19...Bc5 20.e7? (Not precise. 20.Bxc4 gives better chances.) 20...Nc6? (Black's life would be easier after 20...Bxe7.) 21.Bg4+ Kb7 22.Nb5? (A losing move. Three moves, 22.Nf5; 22.Rab1+; and 22.Nb3, give white equal chances.) 22...Qe5 23.Re1 Be4? (23...Qg5! would win.)

24.Rab1 Rxg4 25.Rxe4 Qxe4 26.Nd6+ Kc7 27.Nxe4 Rxe4 28.Qd1 Re5? (Missing a draw. Eliminating the pawn on e7 was necessary: 28...Bxe7, 28...Nxe7 or 28...Rxe7 give black chances to hold.) 29.Rb7+! Kxb7 30.Qd7+ Kb8 31.e8Q+ Rxe8 32.Qxe8+ Kb7 33.Qd7+ Kb8 34.Qxc6 Black resigned.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

Best game

When once asked to name his best game, Tal answered: "As long as I live, I can't." Everybody has his own favorite Tal game. I like his combination against Hans-Joachim Hecht at the Varna olympiad in 1962, but this amazing game almost didn't take place. Tal, a heavy smoker, shared room with Spassky. One morning, around 3:30, Spassky returned to his room only to see Tal's bed in flames and saved him.

Hecht speaks very highly about his encounter with Tal: "The whole game resembles an artistic creation of the highest order. The Latvian artists Juta & Mareks used the position before 19.exf6 to honor their countryman. They recreated it on an one-by-one meter canvas, but they left out the black pawn on c5. In early November 2008, I discovered the piece in an art shop in Munich and immediately bought it even with the artistic mistake."

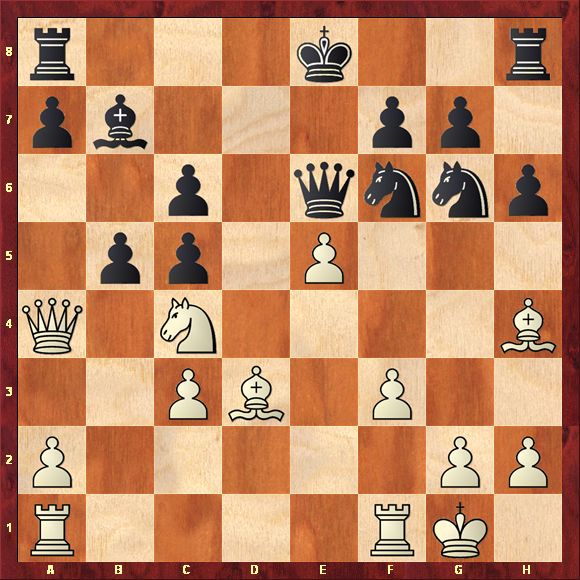

Tal - Hecht

Varna Olympiad 1962

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 b6 4.Nc3 Bb4 5.Bg5 Bb7 6.e3 h6 7.Bh4 Bxc3+ 8.bxc3 d6 9.Nd2 e5 10.f3 Qe7 11.e4 Nbd7 12.Bd3 Nf8 13.c5 dxc5 14.dxe5 Qxe5 15.Qa4+ c6 16.0-0 Ng6 17.Nc4(With a pawn sacrifice, Tal unbalanced the game and opened it up. The hitting begins.)

17... Qe6 18.e5 b5 (Gone is Hecht's solidly-built game. Instead, he finds himself in the middle of Tal's beautiful combinational dance.)

19.exf6!

("I almost fell out of my chair when I saw this reply, since I was counting only with 19.Qb3. But that was not all. Suddenly a large demonstration board appeared on my right and our position was being quickly set up. Sensation-seeking spectators were rushing towards our table. In addition, Tal's teammates were crowding around our board, resembling organ pipes." - Hecht

Tal describes how the temperamental Najdorf, who was watching the game, came over and kissed him. It was a sense of deja vu for the Argentinian grandmaster. The same move, also announcing a queen sacrifice, appeared in the famous game Lilienthal-Capablanca, Hastings 1934/35, in which the young Hungarian master quickly forced the former world champion to resign.

Lilienthal - Capablanca

Hastings 1935

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.a3 Bxc3+ 5.bxc3 b6 6.f3 d5 7.Bg5 h6 8.Bh4 Ba6 9.e4 Bxc4 10.Bxc4 dxc4 11.Qa4+ Qd7 12.Qxc4 Qc6 13.Qd3 Nbd7 14.Ne2 Rd8 15.0-0 a5 16.Qc2 Qc4 17.f4 Rc8 18.f5 e5 19.dxe5 Qxe4

20.exf6!

When Bobby Fischer first met Andor Lilienthal, he would greet him with the word "exf6," an obvious compliment to the amazing queen sacrifice.

20...Qxc2 21.fxg7 Rg8 22.Nd4 Qe4 23.Rae1 Nc5 24.Rxe4+ Nxe4 25.Re1 Rxg7 26.Rxe4+ Kd7 Black resigned.)

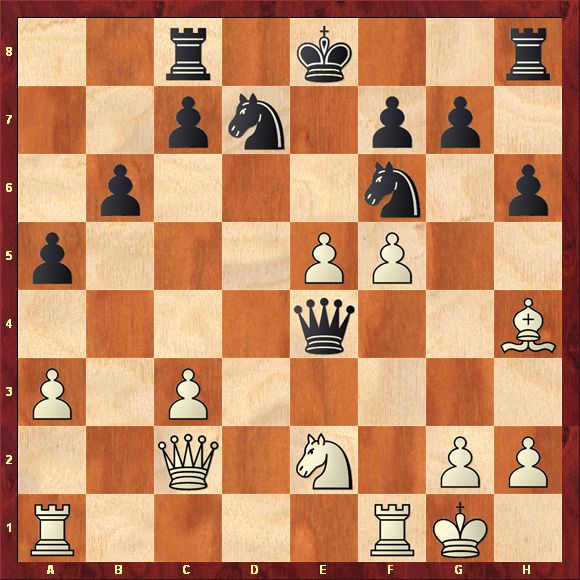

19...bxa4 (According to Tal, Hecht collected the queen without much thought.) 20.fxg7 Rg8 21.Bf5!!

("This is where I lost it. It took me several minutes before I was able to calculate the next variations. Tal considered this game one of the most beautiful of the Olympiad. For me, it represents a wonderful example of harmonious coordination of the pieces. I was still able to find the best defense." - Hecht )

21...Nxh4 (After 21...Qxf5 22.Nd6+ Kd7 23.Nxf5 Nxh4 24.Nxh4 black has a bad endgame; and after 21...Qxc4 22.Rfe1+ Qe6 23.Rxe6+ fxe6 24.Bxg6+ Kd7 25.Rd1+ Kc7 [or25...Kc8 26.Bf6!] 26.Bg3+ Kb6 27.Rb1+ Ka6 28.Bd3+ Ka5 29.Bc7 mates.)

22.Bxe6 Ba6!

("I chose this move not to win a piece, but to remove the terrible white knight." - Hecht) 23.Nd6+ Ke7 24.Bc4 Rxg7 25.g3 Kxd6 26.Bxa6 (The end of the combination. Black is left with a shattered pawn structure. Hecht is not lost by all means, but he has to defend precisely.) 26...Nf5? (Allowing Tal to control the b-file. Black could still defend with 26...Rb8! ) 27.Rab1 f6 28.Rfd1+ Ke7 29.Re1+ Kd6 30.Kf2 c4 31.g4 (31.Re4! picking up a few pawns, wins easily.) 31...Ne7 32.Rb7 Rag8 33.Bxc4 Nd5 34.Bxd5 cxd5 35.Rb4 Rc8? (Missing the last drawing chance. The computers propose to equalize with 35...h5 36.h3 f5; or 35...f5 36.h3 h5.) 36.Rxa4 Rxc3 37.Ra6+ Kc5 38.Rxf6 h5 39.h3 hxg4 40.hxg4 Rh7 41.g5 Rh5 42.Rf5 Rc2+ 43.Kg3 Kc4 44.Ree5 d4 45.g6 Rh1 46.Rc5+ Kd3 47.Rxc2 Kxc2 48.Kf4 Rg1 49.Rg5 Black resigned.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

Mueller and Stolze wrote a fascinating book, bringing out Misha Tal's personality and his magical touch. I am sure it will be appreciated by any chess player. I only wish it would be translated into English soon.