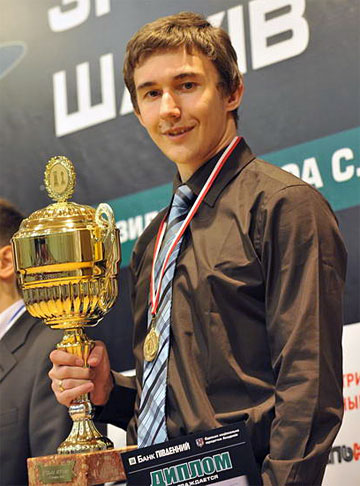

Imagine Usain Bolt, the fabulous Jamaican sprinter and world record-holder, running a 100 meter dash against some of the world's best contenders and winning by 20 meters. This is how the Norwegian chess superstar Magnus Carlsen dealt with the opposition at the elite Kings tournament in Medias, Romania, last week. Undefeated, with five wins and five draws, Carlsen left his nearest rivals two full points behind, scoring 7,5 points in 10 games. It was an amazing display of chess dominance.

Photo by Chessbase.com

Carlsen, 19, is the world's top-rated player and his new rating is projected at 2826, some 23 points above the second-placed Veselin Topalov of Bulgaria. Nobody, except Garry Kasparov, ever climbed that high. It could soon be lonely up there. Every time he plays, Magnus is expected to win, often by big margin.

Carlsen began the event in Medias slowly with three draws, but accelerated the pace with four consecutive wins, leaving the other players a mere spectators. They finished as follows: Teimour Radjabov of Azerbaijan and Boris Gelfand of Israel, both 5,5 points; Ruslan Ponomariov of Ukraine, 4,5 points; Liviu-Dieter Nisipeanu of Romania, 4 points; Wang Yue of China, 3 points.

Appropriately, Carlsen honored the Kings tournament by playing the King's gambit for the first time in his life. The opening evolved over the years. The old romantic masters loved fireworks as presented, for example, in the analysis by the Italian master Gioacchino Greco (1600-1634). To some chess historians, Greco was the first chess professional. Others thought of him as the first chess hustler. Whatever you call him, Greco was a very talented player who made a living by teaching chess to wealthy patrons, including a few kings. In 1619 he wrote a manuscript on openings, consisting of games, probably fictitious, full of combinational fantasy and clarity. Here is Greco's take on the King's gambit.

Greco-N.N.

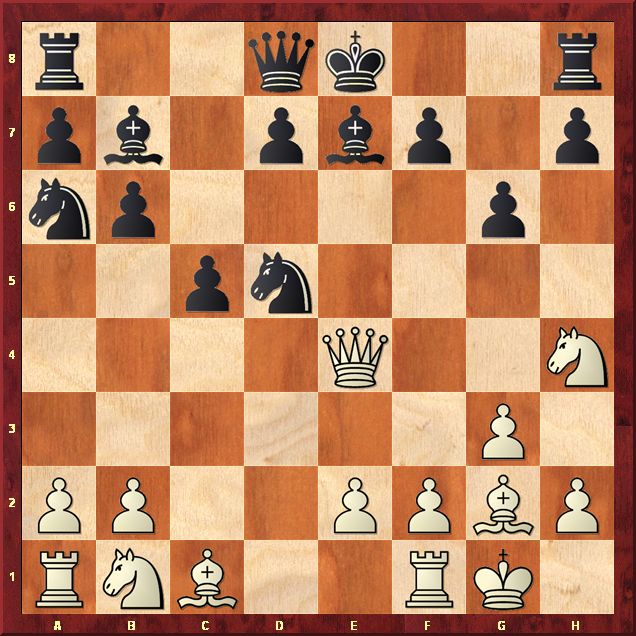

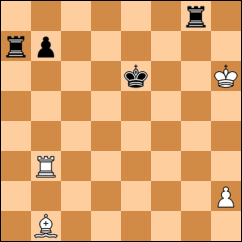

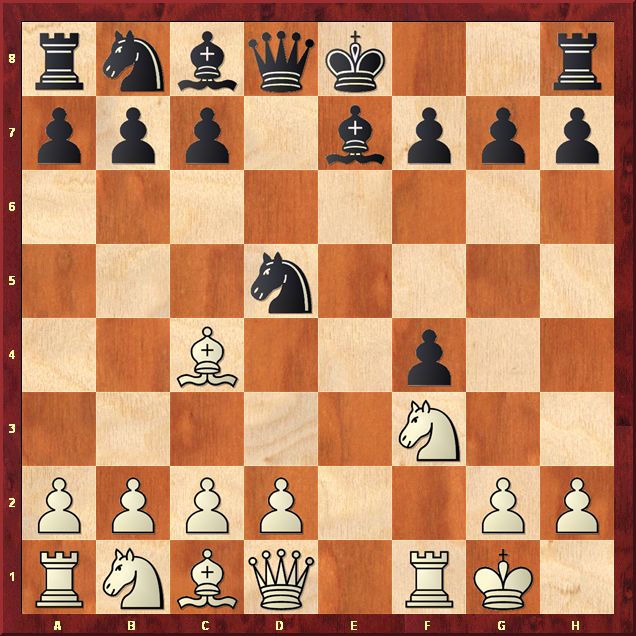

1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Nf3 g5 4.Bc4 g4 5.Bxf7+?! (Speedy assaults on the black King, with sacrifices like this one, flourished in Greco's time. Often not completely correct, they succeeded because they did not meet strong defense.) 5...Kxf7 6.Ne5+ Ke6 (Greedy. Modern theory prefers to refute White's adventurous play with 6...Ke8 7.Qxg4 Nf6, but that is not much fun.) 7.Qxg4+ Kxe5 8.Qf5+ Kd6 9.d4 Bg7 10.Bxf4+ Ke7 11.Bg5+ Bf6 12.e5 Bxg5 13.Qxg5+ Ke8 14.Qh5+ Ke7 15.0-0 (Black is clearly in trouble. His emperor has no clothes.) 15...Qe8

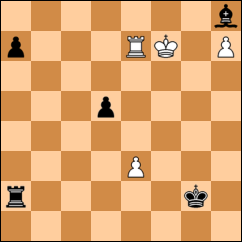

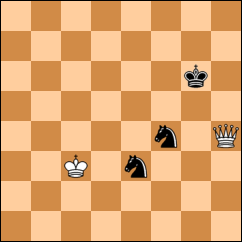

16.Qg5+ (White can shorten the outcome with 16.Qh4+! Ke6 17.d5+ Kxe5 [or 17...Kxd5 18.Nc3+ Ke6 19.Rf6+ Ke7 20.Nd5+ Kd8 21.Rf8+ Ne7 22.Qxe7 mate] 18.Nc3! Kd6 19.Qb4+ c5

20.Nb5+ Kxd5 21.Rad1+ Kc6 [or 21...Ke5 22.Qe1 mate] 22.Rd6 mate.) 16...Ke6 17.Rf6+ Nxf6 (After 17...Ke7 18.Rf4+ Ke6 19.d5+! Kxd5 20.Nc3+ Kc5 21.Rc4+! Kxc4 22.Qh4+ Kc5 23.b4+ white mates soon.) 18.Qxf6+ Kd5 19.Nc3+ Kxd4 (19...Kc4 prolongs the game by a move 20.Qf1+ Kxd4 21.Qf4+ etc.) 20.Qf4+ (20.Rd1+! speeds up the end 20...Kc4 21.Qf1+ Kb4 22.Qb5 mate; or 20...Kc5 21.Rd5+ Kb4 22.Qh4 mate.) 20...Kc5 21.b4+ Kc6 22.Qc4+ Kb6 23.Na4 mate.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

By contrast, Carlsen's treatment of the King's gambit was purely positional. It has been done before, for example, by Akiba Rubinstein and Richard Reti at the beginning of the last century. William Steinitz and Boris Spassky were the finest King's gambit connoisseurs among the world champions. It is possible that Magnus turned to the gambit to avoid the solid Petroff defense the Chinese GM Wang Yue employs regularly. In any case, it worked.

Carlsen -Wang Yue

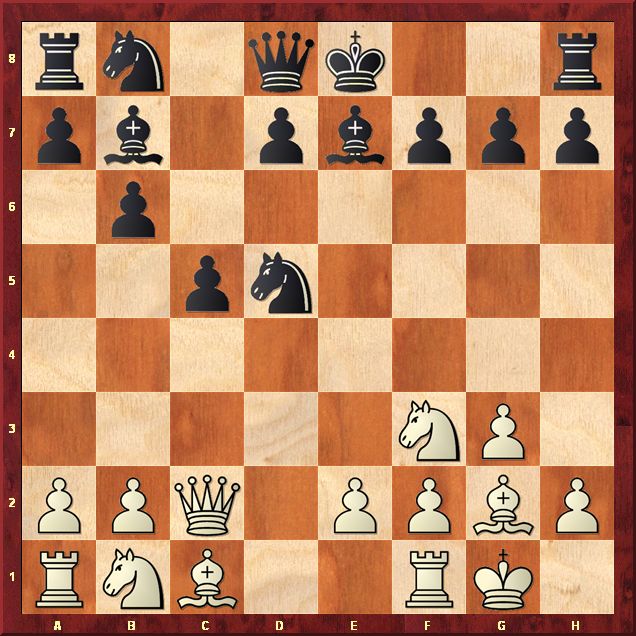

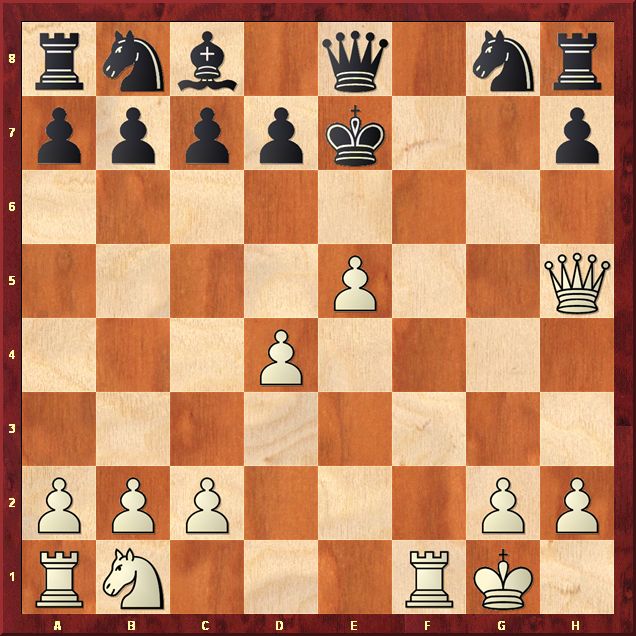

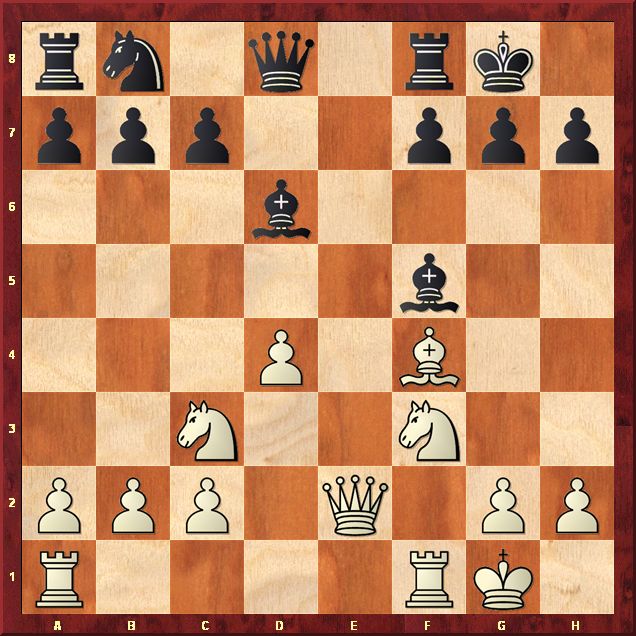

1.e4 e5 2.f4 (The King's gambit is one way to avoid the dreaded Petroff defense 2.Nf3 Nf6.) 2...d5 (In 2004, when he was making his first steps toward stardom, Carlsen as Black played against GM Alexei Fedorov in Dubai 2...exf4 3.Nf3 g5 4.h4 g4 5.Ne5 d6 6.Nxg4 Nf6 7.Nxf6+ Qxf6 8.Nc3 Nc6 9.Bb5 Kd8 10.Bxc6 bxc6 11.d3 Rg8 12.Qf3 Bh6 13.Qf2 Rb8 14.Ne2 Rxb2 15.Bxb2 Qxb2 16.0-0 Qxc2 17.Nxf4 Qxf2+ and the players agreed to a draw since the forced variation: 18.Rxf2 Bg7 19.Rc1 Bd4 20.Rxc6 Rg4 21.Nd5 Bb7 22.Rc4 Bxf2+ 23.Kxf2 Rxh4 24.Nxc7 Rh5 does not give much to either side.) 3.exd5 exf4 (A popular way to defuse the tension in the center.) 4.Nf3 Nf6 (In his new book Starting Out: Open Games, published by Everyman Chess, GM Glenn Flear brings back the move 6...Bd6. It was played in the famous game Boris Spassky-David Bronstein, Leningrad 1960, and the final few moves were reproduced in the James Bond movie "From Russia with Love." The game went 4... Bd6 5.Nc3 Ne7 6.d4 0-0 7.Bd3 Nd7?! 8.0-0 h6? 9.Ne4! Nxd5 10.c4 Ne3 11.Bxe3 fxe3 12.c5 Be7 13.Bc2! Re8 14.Qd3 e2? 15.Nd6!? Nf8?! 16.Nxf7! exf1Q+ 17.Rxf1 Bf5 [17...Kxf7 18.Ne5+ Kg8 19.Qh7+! Nxh7 20.Bb3+ Kh8 21.Ng6#] 18.Qxf5 Qd7 19.Qf4 Bf6 20.N3e5 Qe7 21.Bb3 Bxe5 22.Nxe5+ Kh7 23.Qe4+ and Black resigned since after 23... g6 24.Rxf8! wins. It was one of Spassky's finest achievements and a disaster for Black. For years nobody touched it, but Flear is convinced that after 4...Bd6 5.Nc3 Ne7 6.d4 0-0 7.Bd3 Ng6 8.0-0 c6; or after 4...Bd6 5.Bb5+ c6 6.dxc6 Nxc6 7.d4 Nge7 8.0-0 0-0 9.c4 Bg4 Black has active piece play against White's center.) 5.Bc4!? (The Bishop move is now preferable to 5.Bb5+ or 5.Nc3.) 5...Nxd5 6.0-0 Be7 (Black can invite an interesting gambit with 6...Be6 7.Bb3 Be7 8.c4 Nb6 9.d4 Nxc4, but White seems to have good compensation for the pawn. The game Shulman-Onischuk, Kansas 2003, continued 10.Nc3 c6 [10...Na5 is not bad either.] 11.Bxf4 0-0 12.Qe2 b5 13.a4 Qb6 with roughly equal chances.)

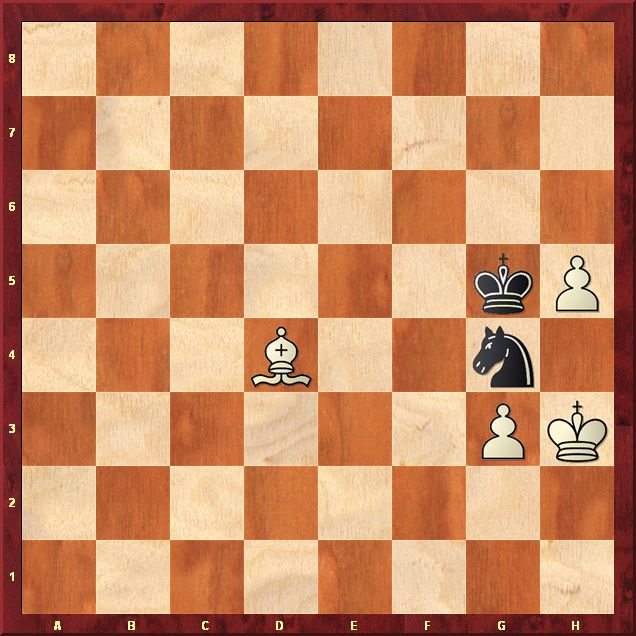

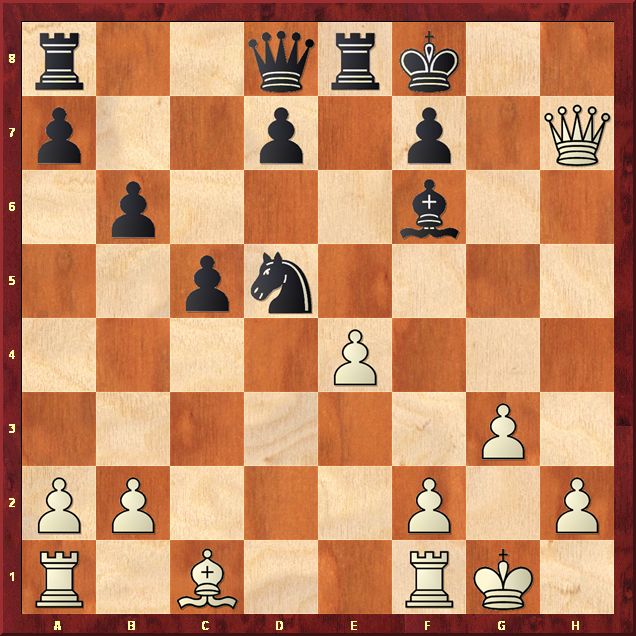

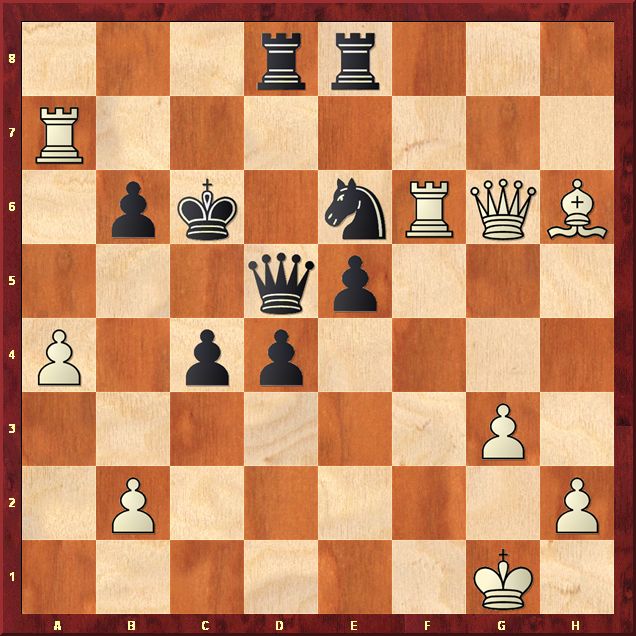

7.Bxd5!? (Why would White give up this wonderful Bishop, which did great damage in many King's gambit games? The answer is: speed in development. White gets his pieces quickly into play, dominates the center and, in general, enjoys more space.) 7...Qxd5 8.Nc3 Qd8 (The Queen moves like a yo-yo, but it is the safest retreat. By protecting the pawn on c7, Black will have more time to develop his light pieces. Holding onto the pawn seems dangerous and definitely not the style of the Chinese grandmaster. It could get wild after 8...Qf5 9.d4 0-0 10.Ne5 g5 11.Nd5 with a possible piece sacrifice on f4.) 9.d4 0-0 10.Bxf4 Bf5 (Wang develops his Bishop and takes the square d3 from the white Queen. But 10...c6 11.Qd3 Na6 12.Rae1 Be6 is a good, playable alternative.) 11.Qe2!? (Carlsen connects the Rooks and Black has to be aware of a timely 12.Qb5. In the game Fedorov-Svidler, Smolensk 2000, Black was able to secure the light squares after 11.Qd2 c6 12.Kh1 Bb4 13.a3 Bxc3 14.Qxc3 Qd5 15.Qd2 Nd7 16.b3 b5 17.Rac1 Nb6. He later outplayed his opponent and won in 41 moves.) 11...Bd6?! (Exchanging pieces in a worse position is a common ploy of good defenders, but here it leads to more yo-yo moves by the black Queens and helps Carlsen to improve his position. Wang probably didn't like 11...c6 12.Rae1 Re8 13.Bg5 with White's edge.)

12.Bxd6 Qxd6 13.Nb5! (Improving the "marriage" between the c-pawn and the white Knight. David Bronstein believed that the Knight behind the pawn is a good marriage and in front of the pawn - a bad one.) 13...Qd8 (The safest retreat. After 13...Qb6 14.Qe5 Bxc2 15.Nxc7 Nd7 16.Nxa8 White should win; and after 13...Qd7 14.Ne5 Qc8 15.Rxf5! Qxf5 16.Rf1 Qc8 17.Qc4 the attack is decisive.) 14.c4 a6 (Black doesn't want to engage his c-pawn too soon, but 14...c6!? 15.Nc3 Re8 16.Qd2 Nd7 is a better defensive set-up.) 15.Nc3 (Now the Knight is behind the pawn and Bronstein would be happy. White controls most squares in the center and can turn it into a space advantage.) 15...Nd7 16.Rad1 Bg6 17.Qf2 Re8 18.h3 Rc8 19.Rfe1 Rxe1+ 20.Rxe1 c6 (Preventing the unpleasant 21.Nd5.)

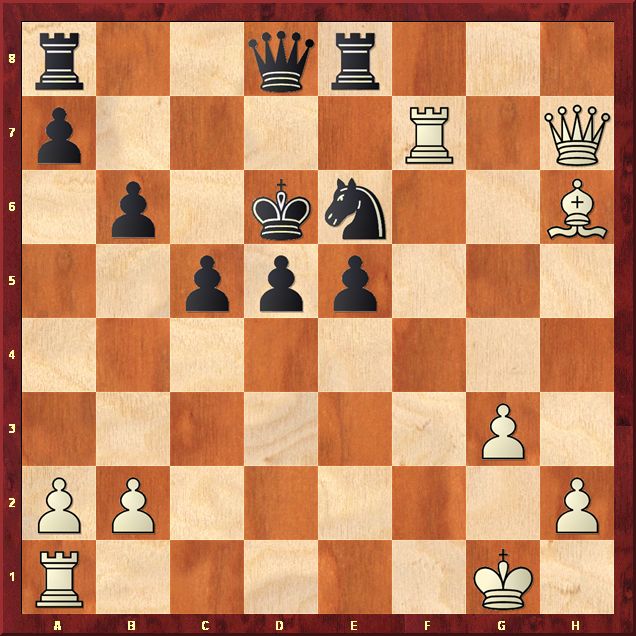

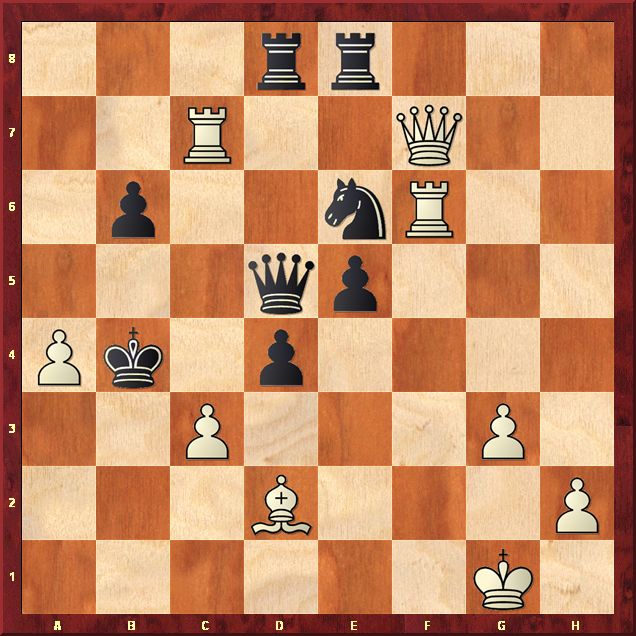

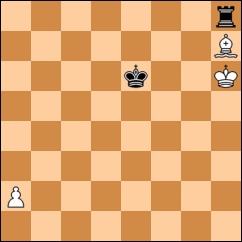

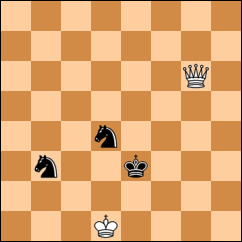

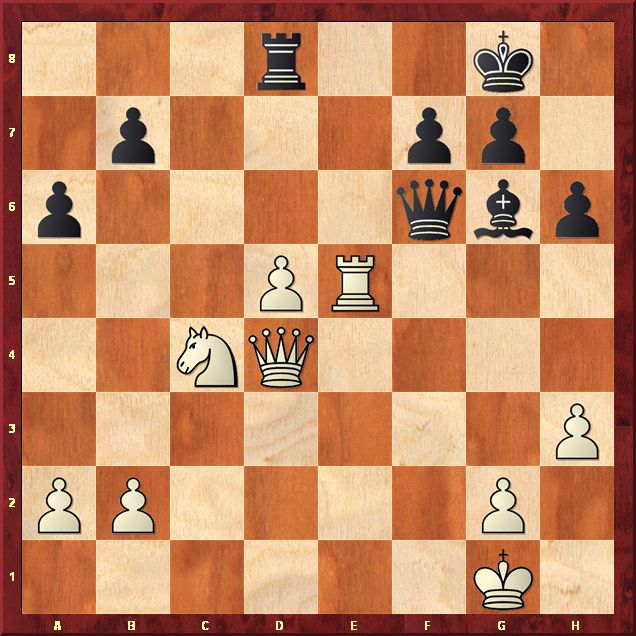

21.d5! (Crossing the equator, the line that splits the board in half horizontally, dividing both armies. Carlsen intends to advance the passed d-pawn as far as he can.) 21...Nf6 (Black should have exchanged the pawn immediately to keep more pieces in play. After 21...cxd5 White has to retake with the pawn 22.cxd5, since 22.Nxd5?! allows 22... Rxc4.) 22.Qd4 cxd5 23.Nxd5! (Threatening 24.Ne7+, White forces the knight exchange, eliminating one blocker.) 23...Nxd5 24.cxd5 Qd6 (The Queen is usually a poor blocker, but Black doesn't have anything else handy.) 25.Ne5 Re8 (The immediate 25...Rd8 was possible, but Black had a reason to lure the white Rook on e3. However, Wang should have clarified the position with 25...f6! 26.Nxg6 [26.Nc4? Qb4! loses.] 26...hxg6, for example 27.Re6 [Otherwise Black plays 27...Rd8.] 27...Rc1+ 28.Kf2 Rc2+ 29.Kf3 and now after either 29...Qd7; or even 29...Qh2 30.Qg4 Kf7! Black can equalize.) 26.Re3 Rd8 27.Nc4 Qf6 28.Re5!? (Carlsen decides to keep the Queens on the board. After 28.Qxf6 gxf6 the White Rook can't protect the d-pawn since the square d3 is taken and after 29.Re7 Bb1! 30.a3 [or30.a4] 30...b5 Black has good drawing chances.) 28...h6 (The computers want to play 28...b5 29.Na5 h6, but after 30.Nb7 Rb8 31.Nc5! Qd6 32.b4 the position looks better for White. With the help of tactical tricks Carlsen is now able to march his d-pawn forward.)

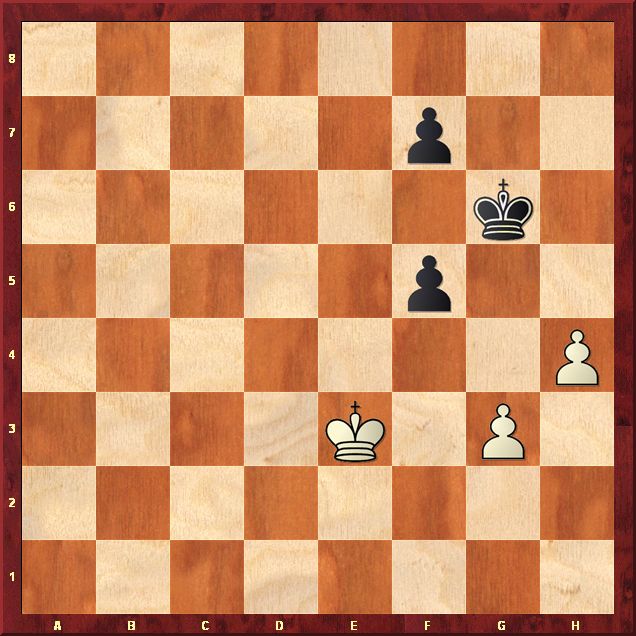

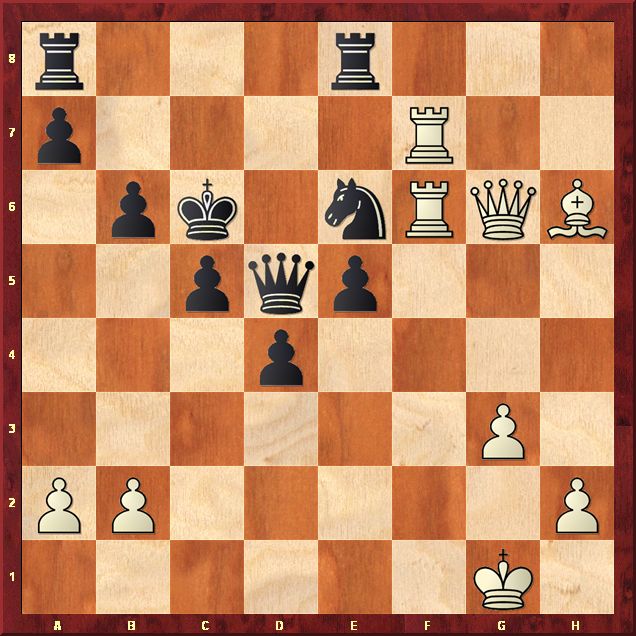

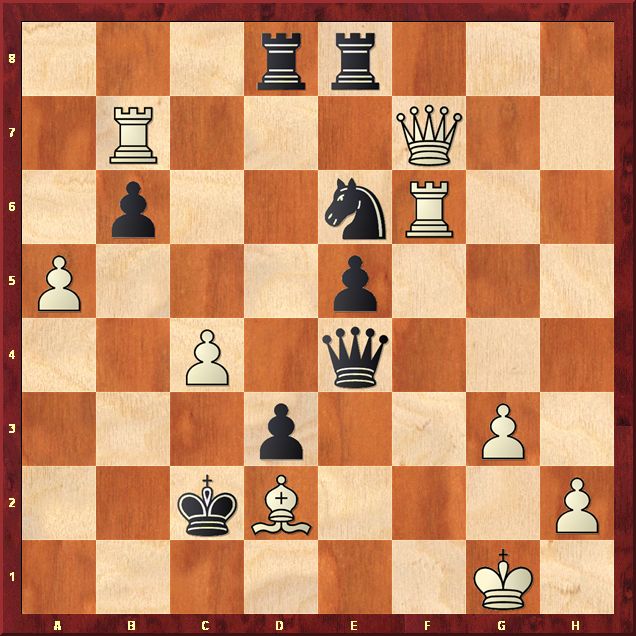

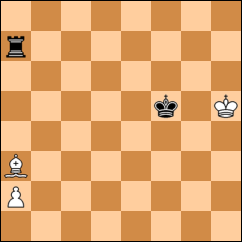

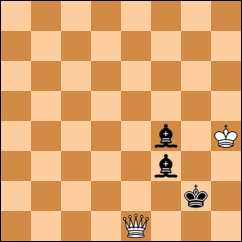

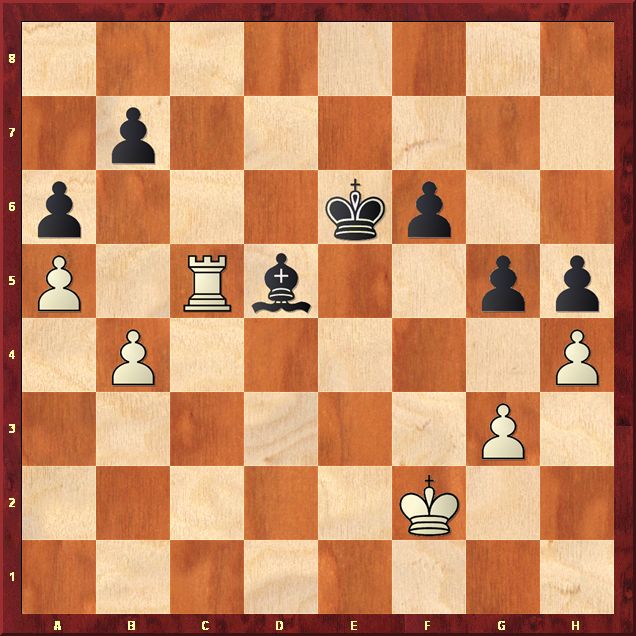

29.d6! (Did Black overlook this advance?) 29...Bf5 (After 29...b5 30.d7! bxc4 31.Re8+ Kh7 32.Qxf6 gxf6 33.Rxd8 wins.) 30.Nb6! Be6 (Black still can't touch the d-pawn: after 30...Qxd6 31.Re8+ wins outright and after 30...Rxd6 31.Nd5! Black has to surrender the Exchange since 31...Qg5 32.Rxf5! Qxf5 33.Ne7+ Kf8 34.Nxf5 loses a piece. Black could have considered to maneuver his Bishop to the diagonal h1-a8: 30...Bd3 31.d7 Bb5 32.a4 Qf1+ 33.Kh2 Bc6 with some hope to survive.) 31.d7! (Black is in a terrible squeeze and Carlsen has time to improve his pieces.) 31...Kh8 32.a4 g6 33.Qc3 Kg7 34.a5 h5 35.h4 Rxd7!? (This could be Black's best practical chance to avoid a slow death. After 35...Kg8 36.g3 Kg7 37.Rc5 Qxc3 38.Rxc3 Kf6 39.Rc7 White has excellent winning chances, for example 39...Ke7 40.Rxb7 Bxd7 41.Ra7+- Ke8 42.Rxa6 Bb5 43.Ra8 Rxa8 44.Nxa8 Kd7 45.Kf2 Kc6 46.Ke3 Bf1 47.Kd4 Kb5 48.Nc7+ Kxa5 49.Kc5 and the b-pawn runs to victory.) 36.Nxd7 Bxd7 37.Qd4 Bc6 38.b4 Bb5 39.Kh2 Ba4 40.Rd5 Bc6 41.Qxf6+ Kxf6 42.Rc5 Ke6 43.Kg3 f6 44.Kf2 Bd5 45.g3 g5? (Allowing a pretty breakthrough. Black should have waited, not allowing the white Rook to penetrate to the back rank. If the white King begins to cross to the square b6, Black can push his g-pawn, hoping to create a passed pawn on the kingside. It could be close.)

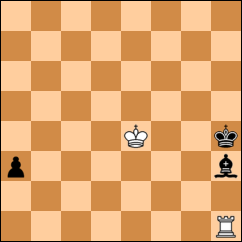

46.g4! hxg4 47.h5 Be4 48.Rc7! (Supporting the passed h-pawn and not allowing the black King to come closer.) 48...f5 49.h6 f4 50.h7 g3+ 51.Ke1 f3 52.h8Q f2+ 53.Ke2 Bd3+ 54.Ke3 (After 54...f1Q 55.Qe8+ Kf5 56.Rf7+ wins.) Black resigned.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

For Gambit Fans

Marco Saba has created the Encyclopedia of Gambits

The monumental work covers more than 700 gambits played in 450 years, since 1560, the date of Ruy Lopez book, till this year. The web site is in Italian and partly in English but can be followed easily. Many interesting statistics, lists of players, games and even evaluations are included. Some of the gambit names look funny, but it is worth a visit.

Magnus Carlsen finished the Kings Tournament in Bazna, Romania in style. The Norwegian beat Wang Yue with Black in the last round to finish with a 7.5/10 score, two points ahead of the rest of the field. Ponomariov and Radjabov defeated Nisipeanu and Gelfand respectively, also with the black pieces. For now the games, later more.

Magnus Carlsen finished the Kings Tournament in Bazna, Romania in style. The Norwegian beat Wang Yue with Black in the last round to finish with a 7.5/10 score, two points ahead of the rest of the field. Ponomariov and Radjabov defeated Nisipeanu and Gelfand respectively, also with the black pieces. For now the games, later more.