The last move could have been: 31.Rg7! followed by Rh7 #

Thursday, December 31, 2020

Sunday, December 27, 2020

A very interesting analyzing tool: decodechess.com

Chess Analysis, Powered by AI

The first AI chess tutor, DecodeChess explains the why behind chess moves in rich, intuitive language. Start improving your chess with the most advanced chess analysis software.

You can analyze two games each day for free online with decodechess.com. Example (click on the image to enlarge):

Game: 1. e4 d5 2. exd5 Nf6 3. d4 Nxd5 4. c4 Nb4 5. a3 N4a6 6. Nf3 c5 7. d5 g6 8. Nc3 Bg7 9. Be3 O-O 10. Qd2 e5 11. h4 Bg4 12. Nh2 Bd7 13. h5 f5 14. Bh6 Qf6 15. Bxg7 Qxg7 16. hxg6 hxg6 17. Nf3 Nc7 18. O-O-O Ne8 19. Qg5 Nd6 20. Nxe5 Qxe5 21. Qxg6+ Qg7 22. Qxd6 b6 23. Rh6 Be8 24. Rd3 Nd7 25. Rg3

Saturday, December 26, 2020

2020: The year of a pandemic of cheating

2020: The year of a pandemic of cheating in online chess

As chess gains popularity online, instances of cheating too have seen a spike. How can organisers keep a check when participants are playing from their homes?

2020 has been a unique year for chess. In the first half, as countries across the world went into lockdowns to stem the spread of covid-19, millions discovered the game—online. Websites like chess.com, chess24.com and lichess.org saw a sharp jump in the number of users and games played. In the second half, Netflix released The Queen’s Gambit, a web-series about a female chess player battling her demons to beat the best in world chess. The game’s popularity surged. Unfortunately, so did cases of cheating.

In a post in August, chess.com, the biggest of the online chess platforms, said closure rates of accounts had more than doubled since the covid-19 outbreak in December 2019. The website had been closing nearly 500 chess accounts every day. Offences included using chess engines to play matches, rating manipulation, sandbagging (deliberately losing games to lower one’s rating and become eligible for lower-rated tournaments with prize money) and other fair-play violations. Those against whom action was taken include grandmasters, the elite players in world chess.

The director general of the world chess body FIDE, Emil Sutovsky, has been quoted as saying that stemming cheating is “a huge topic I work on dozens of hours each week”. Its president, Arkady Dvorkovich, has called “computer doping” a “real plague”. “In chess.com's history,” from 2007 till August 2020, “we have closed nearly half a million accounts for cheating,” the website says. “Our projections predict we will reach 500,000 accounts closed by February 2021 and one million accounts by mid-2023.” There has been a sharp jump since the outbreak. In December 2019, it had shut 6,044 accounts. In August, it closed 15,130.

So how does one stop cheating in online chess?

This was the question Sotirios Logothetis and his team at chess24.com found themselves faced with when they decided to organise online tournaments earlier this year.

“Cheating is extremely rare in offline events, especially at the top tier,” says Logothetis, who is also an international chess arbiter. “The main advantage there is, you have full visual contact, which allows the arbiter to latch on to suspicious behaviour.” In addition, marquee tournaments also use metal detectors and check the players physically for sophisticated devices, like a micro earpiece with voice transmitters. “Online chess doesn’t offer these advantages,” says Logothetis.

The solution, Logothetis’ team found, lay in the way some universities around the world conduct examinations: webcams and screen-share. In the tournaments they have conducted since March, including the rapid-chess tournament Skilling Open and the Magnus Carlsen Invitational, each player had to have at least two cameras: one in front, another at the back or the side. They also installed a software so that the computer screen could be shared with the arbiters during playing sessions.

The cameras, which the organisers sent to the players’ houses, stored the audio and video footage in a memory card even if the internet connection was interrupted. After each session, players were expected to upload the entire footage on the server cloud. These two tournaments had around a dozen players each, so it was possible to send equipment, upload and verify.

Most online tournaments conducted this year, including the FIDE Online Olympiad 2020, have used a combination of such techniques. There is even a system to scan a player’s game, study performance patterns and highlight unusual activities, such as if a player is making the kind of moves a chess engine would, or if a low-ranked player suddenly starts playing exceedingly well. Anything, in other words, that doesn’t fit the pattern.

“I think our systems can cover 95% of possible ways of cheating online,” says Logothetis. But, he accepts, it can never be foolproof. “If someone tries really hard to cheat, I think they will find a way,” he adds. “But someone who is doing this has to be truly dedicated.”

So, while marquee tournaments may have developed robust systems, for most online players cheating is only a few clicks or fingertaps away. “The simplest way is, you have a phone, enter a question and ask for the best moves,” says grandmaster (GM) Srinath Narayanan. “Stockfish (the best open-source chess engine) is free and easily accessible. There are also extensions on web browsers that show the next best move.”

It’s possible to game a platform’s in-built scanners too. “If someone is smart, they can make a couple of moves by themselves, and for some important ones, they can take the help of engines,” says GM Harika Dronavalli, India’s No.2 woman chess player.

Cheating is rampant in online chess, Narayanan reckons. It’s not just a matter of pride—some tournaments offer cash prizes too. Narayanan, who coaches the 16-year-old chess prodigy Nihal Sarin, says: “I know young kids also have cheated during games. Some of them have been caught and banned by popular websites, some haven’t been.” The penalties aren’t strict enough, he adds. “If you confess, you don’t play in prized events for a year but you can have your account back. And if a player is banned from one website, they can always play on another.”

Some platforms, however, are keen on setting an example. In October, chess.com suspended Armenian GM Tigran Petrosian for allegedly using computer assistance during the finals of the Pro Chess League—one of 46 GMs against whom action has been taken since 2007. In its investigation, the website found that some of Petrosian’s moves were consistent with chess-engine suggestions. He also allegedly looked down often, which the investigators concluded was to consult a computer. Petrosian has vehemently denied the allegations.

“I was surprised when I saw Tigron’s news,” says Dronavalli. “Most players I know won’t think of that. Even if there are people who are ready to cheat, I don’t think they should take risk of a whole career for an online tournament.”

In the past year, Dronavalli has played several marquee online tournaments, including Titled Tuesdays, Online Chess Olympiad and the Online Nations Cup. For the most part, she says, the checks were robust: You shared your screen during gameplay, you couldn’t mute yourself and you couldn’t open any other files on the computer. Before a game, the organisers would ask for a camera-tour of the room she was playing in. “If I switched off my webcam or exited the room, I would have to repeat the whole thing all over again. It would get tiring sometimes but you have to do it.”

She, too, acknowledges that anti-cheating measures can never be as foolproof as they are for an offline event. But cheating will only get you so far. “Finally, you need to have talent,” says Dronavalli. “If you are not consistent, no one will believe your performances.”

Friday, December 25, 2020

Tuesday, December 15, 2020

Il bianco muove e matta in tre

Questo è interessante: avevo visto subito: 1.Cf6 Rg7 2.Cg8 Rf8 3.Ab4 e guadagna il cavallo. Ma in effetti si può dare matto...

Monday, December 7, 2020

Thursday, November 26, 2020

Sunday, November 22, 2020

Sunday, November 1, 2020

Martenson: We Are Pawns In A Bigger Game

Martenson: We Are Pawns In A Bigger Game Than We Realize

Authored by Chris Martenson via PeakProsperity.com,

“I had grasped the significance of the silence of the dog, for one true inference invariably suggests others…. Obviously the midnight visitor was someone whom the dog knew well.”

~ Sherlock Holmes – The Adventures of Silver Blaze

Is it possible to make sense out of nonsense?

So much these days is an incoherent mess. It’s complete nonsense.

Page 1 excitedly beams about a glorious rebound in GDP. Yay economic growth!

Page 2 worryingly notes the near complete failure of Siberian arctic ice to reform during October and that hurricane Zeta (so many storms this year we’re now into the Greek alphabet!) has made punishing landfall.

Each is a narrative. Each has its own inner logic.

But they simply do not have any external coherence to each other. It’s nonsensical to be excited about rising economic growth while also concerned that each new unit of growth takes the planet further past a critical red line.

These narratives are incompatible. So which one should we pick?

Well, in the end, reality always has the final say. As Guy McPherson states: Nature bats last.

So better we choose to follow the narrative that hews closest to what reality actually is, vs what we desperately want it to be.

‘They’ Don’t Care About Us

While issues like climate change and economic growth may be difficult to fully grasp and unravel, direct threats to our lives &/or livelihoods are much more concrete and something we can react to and resist.

Such immediate and direct threats are now fully in play and, once again, they’re accompanied by narratives that are completely at odds with each other. I’m speaking of Covid and the ways in which our national and global managers are choosing to respond (or not).

It’s a truly incoherent mess about which both social media and the increasingly irrelevant media are working quite hard to misinform us.

The mainstream narrative about Covid-19, in the West, is this:

-

It’s a quite deadly and novel disease

-

There are no effective treatments

-

Sadly, no double-blind placebo controlled trials exist to support some of the wild claims out there about various off-patent, cheap and widely available supplements and drugs

-

Health authorities care about saving lives

-

They care so much, in fact, that along with politicians they’ve decided to entirely shut down economies

-

There’s a huge second wave rampaging across the US and Europe and there’s nothing we can do to limit it except shut down businesses and people’s ability to travel and gather

-

You need to fear this virus and its associated disease

-

All we can do is wait for a vaccine

The alternative narrative, one that I’ve uncovered after 9 months of almost daily research and reporting, is this:

-

It’s not an especially dangerous disease and it’s certainly not novel

-

There is a huge assortment of very effective, cheap and widely-available preventatives and treatments including (but not limited to)

-

Vitamin D

-

Ivermectin

-

Hydroxychloroquine

-

Zinc

-

Selenium

-

Famotidine (Pepcid)

-

Melatonin

-

-

Use of a combination of these mostly OTC supplements could reasonably be expected to drop the severity of illness and the already low mortality rate by 90% or (probably) more

-

Western health authorities have shown either zero interest in the results of studies mainly conducted in poorer nations on these combination therapies or…

-

They have actively run studies designed to fail so that these cheap, effective therapies could be dismissed or…

-

Set up proper studies but which started late, have immensely long study periods and most likely won’t be done before a vaccine is hastily rushed through development.

By the way – every single one of my assertions and claims is backed by links and supporting documentation from scientific and clinical trials and studies. I am not conjecturing here; I am recounting the summary of ten months’ worth of inquiry.

The conclusion I draw from my narrative (vs. theirs) is that we can no longer assume that the public health or saving lives has anything to do with explaining or understanding the actions of these health “managers” (I cannot bring myself to use the word authorities).

After we eliminate the impossible – which is that somehow these massive, well-funded bodies have missed month after month of accumulating evidence in support of ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, vitamin D, NAC, zinc, selenium and doxycycline/azithromycin – what remains must be the truth.

As improbable as it seems, the only conclusion we’re left with is that the machinery of politics, money and corporate psychopathy is suppressing life saving treatments because these managers have other priorities besides public health and saving lives.

This is a terribly difficult conclusion, because it means suspending so much that we hold dear. Things like the notion that people are basically good. The idea that the government generally means well. The thought that somehow when the chips are down and a crisis is afoot, good will emerge and triumph over evil.

I’m sorry to say, the exact opposite of all of that has emerged as true.

Medical doctors in the UK NHS system purposely used toxic doses of hydroxychloroquine far too late in the disease cycle to be of any help simply to ‘make a point’ about hydroxychloroquine. They rather desperately wanted that drug to fail, so they made it fail.

After deliberately setting their trial up for failure, they concluded: “Hydroxychloroquine doesn’t help, and it even makes things worse.”

Note that in order to be able to make this claim, they had to be willing to cause harm — even to let people die. What kind of health official does that?

Not one who actually has compassion, a heart, or functioning level of sympathy. It’s an awful conclusion but it’s what remains after we eliminate the impossible.

Getting Past The Emotional Toll

Science has proven that cheap, safe and significantly protective compounds exist to limit both Covid-related death and disease severity.

Yet all of the main so-called health authorities in the major western countries are nearly completely ignoring, if not outright banning, these safe, cheap and effective compounds.

This is crazy-making for independent observers like me (and you) because the data is so clear. It’s irrefutable at this point. These medicines and treatments not only work, but work really, really well.

However most people will be unable to absorb the data, let alone move beyond it to wrestle with the implications. Why? Because such data is belief-shattering. Absorbing this information is not an intellectual process; it’s an emotional one.

I don’t know why human nature decided to invest so much in developing a tight wall around the belief systems that control our actions and thoughts. But it has.

I’m sure there was some powerful evolutionary advantage. One that’s now being hijacked daily by social media AI programs to nudge us in desired directions. One that’s being leveraged by shabby politicians, hucksters, fake gurus, and con men to steer advantage away from the populace and towards themselves.

The neural wiring of beliefs is what it is. We have to recognize that and move on.

Some people will be much faster in their adjustment process than others. (Notably, the Peak Prosperity tribe is populated with many fast-adjusters, which is unsurprising given the topics we cover…tough topics tend to attract fast adjusters and repel the rest)

To move past the deeply troubling information laid out before us requires us to be willing to endure a bit of turbulence. It’s the only way.

For you to navigate these troubling times safely and successfully, you’ll need to see as clearly as possible the true nature of the game actually being played. To see what the rules really are – not what you’ve been told they are, or what you wish or hope they are.

The Manipulation Underway

The data above strongly supports the conclusion that our national health managers don’t actually care about public health generally or your health specifically.

If indeed true, then the beliefs preventing most people from accepting this likely include:

-

Wanting to believe that people are good (a biggie for most people)

-

Trust and faith in the medical system (really big)

-

Faith in authority (ginormous)

There are many other operative belief systems I could also list. But this is sufficient to get the ball rolling.

Picking just one, how hard would it be for someone to let go of, say, trust in the medical system?

That would be pretty hard in most cases.

First not trusting the medical system might mean having to wonder if a loved one might have died unnecessarily while being treated. Or realizing that you’re now going to have to research the living daylights out of every medical decision before agreeing to it. Or worrying that your medications might be more harmful to you over the long haul than helpful (which is true in many more cases than most appreciate). It might mean having your personal heroes dinged by suspicion — perhaps even your father or mother who worked in the medical profession. It would definitely require a complete reorientation away from being able to trust anything you read in a newspaper, or see on TV, about new pharmaceutical “breakthroughs”.

Trust, which is safe and warm and comforting, then turns into skepticism; which is lonelier and insists upon active mental involvement.

But, as always, hard work comes with benefits — with a healthy level of skepticism and involvement, the families of those recruited into the deadly UK RECOVERY trial could have looked at the proposed doses of HCQ (2,400 mg on day one! Toxic!) and said, “Not now, not ever!” and maybe have saved the life of their loved one.

Look at that tangled mess of undesirables that comes with unpacking that one belief: regret, uncertainty, shame, doubt, fallen idols, and vastly more additional effort. Are all up for grabs when we decide to look carefully at the actions of our national health managers during Covid.

Which is why most people simply choose not to look. It’s too hard.

I get it. I have a lot of compassion for why people choose not to go down that path. It can get unpleasant in a hurry.

But, just like choosing to ignore a nagging chest pain, turning away in denial has its own consequences.

The Coming ‘Great Reset’

My coverage of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus) and Covid-19 (the associated disease) has led me to uncover some things that have made me deeply uncomfortable about our global and national ‘managers’. Shameful things, really. Scary things in their implications for what we might reasonably expect (or not expect, more accurately) from the future.

Once we get past the shock of seeing just how patently corrupt they’ve been, we have to ask both What’s next? and What should I do?

After all, you live in a system whose managers either are too dumb to understand the Vitamin D data (very unlikely) or have decided that they’d rather not promote it to the general populace for some reason. It’s a ridiculously safe vitamin with almost zero downside and virtually unlimited upside.

Either they’re colossally dumb, or this is a calculated decision. They’re not dumb. So we have to ask: What’s the calculation being performed here? It’s not public safety. It’s not your personal health. So… What is it?

This is our line of questioning and observation. It’s like the short story by Arthur Conan Doyle in Silver Blaze that many of us informally know as “the case of the dog that didn’t bark”. As the story goes, because of a missing clue – a dog who remained silent as a murder was committed – this conclusion could be drawn: the dog was already familiar with the killer!

The silence around Vitamin D alone is extremely telling. It is the pharmacological dog that did not bark.

One true inference suggests others. Here, too, we can deduce from the near total silence around Vitamin D that the health managers would prefer not to talk about it. They don’t want people to know. That much is painfully clear.

Such lack of promotion (let alone appropriate study) of safe, effective treatments is a thread that, if tugged, can unravel the whole rug. The silence tells us everything we need to know.

Do they want people to suffer and die? I don’t know. My belief systems certainly hope not. Perhaps the death and suffering are merely collateral damage as they pursue a different goal — money, power, politics? Simply the depressing result of a contentious election year? More than that?

We’ve now reached the jumping off point where we may well find out just how far down the rabbit hole goes.

A massive grab for tighter control over the global populace is now being fast-tracked at the highest levels. Have you heard of the Great Reset yet?

If not, you soon will.

In Part 2: The Coming ‘Great Reset’ we lay out everything we know so far about the multinational proposal to transform nearly every aspect of global industry, commerce, trade, and social structure.

If you read on, be ready and willing to let go of cherished beliefs and to suspend what you know to be true. Because none of us has that in hand. It’s going to be a wild ride from here.

Something very big is afoot and I suspect that Covid-19 is merely an excuse providing cover for a much bigger power grab over the world’s wealth and peoples.

Click here to read Part 2 of this report (free executive summary, enrollment required for full access).

Friday, October 23, 2020

Saturday, October 17, 2020

Saturday, October 10, 2020

Sunday, October 4, 2020

Monday, September 28, 2020

Tuesday, September 22, 2020

On the origins of chess

On the origins of chess (7/7)

Find the right combination! ChessBase 15 program + new Mega Database 2020 with 8 million games and more than 80,000 master analyses. Plus ChessBase Magazine (DVD + magazine) and CB Premium membership for 1 year!

1: Introduction | 2: India | 3: China | 4: Egypt | 5: Myths, legends | 6: Cultural syncretism

Part 7: Epilogue

At this point of the investigations on the origin of chess there are things we know, things we suppose we know and things that we ignore. Let’s list them one by one:

We know that the game arose in the Orient.

We know that there are only three theories that present valid sources to support their stance on the original source of the game: the one that locates the origin in India; the one that focuses on China, and that of cultural syncretism.

We know that a variant of proto-chess entered Persia in the sixth century AD coming from a region of India.

We suppose that this game was chaturanga, in its two-player modality, which was taken to present-day Baghdad, the capital of the Persian Empire.

We know that the first precise mentions to a variant of proto-chess, coming from diverse literary sources, appear in the fourth century AD, the first of which refers to the Chinese xiang-qi and the second one to chaturanga.

We know that both xiang-qi and chaturanga had their respective transformation processes.

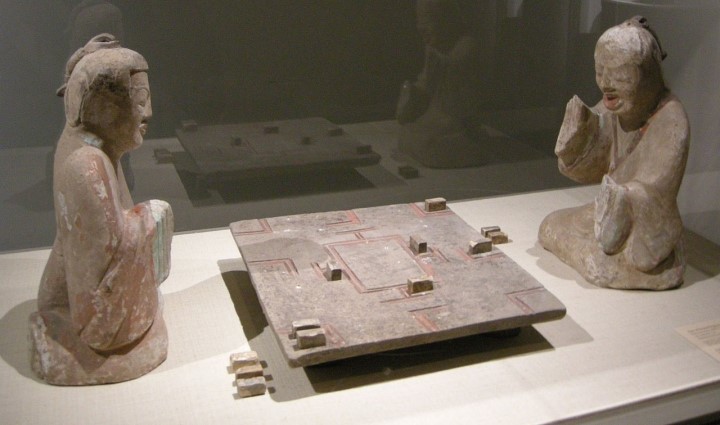

We know that there are two previous games that were born in these cultures, which had been recorded in literary works since ancient times: the Chinese liubo and the Indian ashtāpada.

We suppose that xiang-qi — if it came exclusively from the Chinese culture — could have been conceived from liubo.

We suppose that chaturanga — if it came exclusively from the Indian culture — could have been conceived from ashtāpada or chaturaji.

We ignore the sequence in which chaturaji and chaturanga came to be (although the predominant theory is that the latter came first), or even if chaturaji is a mere position of chaturanga.

We know that a version of xiang-qi has survived to the present day (it is currently played in China and, at least, also in Vietnam) while chaturanga disappeared as a practice at some distant moment in time.

We ignore under which precise circumstances chaturanga abandoned the use of dice.

We ignore whether the evolutionary process of chaturanga went from the four-player version to the two-player one or the other way around.

We suppose that a synthesis of several previous games was generated on the Silk Route, appearing a new prototype that later turned into chess.

We ignore if, at the end of that process, only one game arose or, if on the contrary, both chaturanga and xiang-qi appeared simultaneously.

We suppose that the games that were part of the process of cultural syncretism were liubo, ashtāpada and the Greek petteia, and possibly the process took place under the influence of an old astrolabe of Babylonian origin.

We suppose that this symbiosis occurred in a period of time between the second century BC and the third century AD.

We suppose that the process took place in a vast region occupied successively by the Kingdom of Bactria and the Kushán Empire

We know that the oldest archaeological findings of pieces that were used in some variant of proto-chess — which correlate perfectly with the geographical zones linked to the Silk Route — existed approximately in the sixth century AD.

We suppose that in the future other important archaeological elements will be discovered that, depending on their location, characteristics and antiquity, will strengthen our knowledge regarding this matter.

We know that it is necessary to deepen the analysis with regard to the theory of games, establishing greater precision and causal relationships between the various variants of proto-chess and linked practices — namely ashtāpada, chaturanga, chaturaji, liubo, xiang-qi, petteia and others.

We know that there is much yet to be investigated on the origin of chess.

We suppose that we will eventually find an answer that, without becoming an absolute certainty, at least will allow us to find a major consensus, thus establishing a uniform explanatory paradigm on the origin of chess.

Master Class Vol.9: Paul Morphy

Learn about one of the greatest geniuses in the history of chess! Paul Morphy's career (1837-1884) lasted only a few years and yet he managed to defeat the best chess players of his time.

Statuettes probably from the first to the second century of the Christian era representing two players disputing a game of liubo. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Epilogue

Chess might be the product of a cooperative process — and we would prefer it to be this way, to show that Humanity has the capacity to be virtuous at times (although it is known that it usually favours quarrels, often bloody, between people who seem to forget that they come from a common origin). The game could also have been an invention/creation/discovery of a single culture. Anyway, there is only one thing that is entirely certain: as Borges correctly pointed out, chess comes from the East.

In that sense, we have presented the different protohistoric versions regarding the origins of the game, focusing on that geographical space (India, China, Persia and other undetermined spots within the Silk Road), with physical or literary records that refer to a few centuries before and after the arrival of Christ.

There are quite exact records of many specific episodes, such as the time when one of the versions of the game entered Ctesifonte from India, which happened exactly in the sixth century AD. From that moment on, everything is quite clear, in terms of the diffusion of chess; before this event, however, everything is much less clear.

In this context of uncertainty, there are conflicting theses on the origin of chess, some of which have empirical support while others can only be recognized as myths or legends. All of them, with the inevitable omissions born out of the vastness of the analytical field, were compiled in this work.

After all, there are mainly three possibilities with a high degree of truthfulness and verisimilitude: two of them correspond to particular cultures — those that consider that chess comes from the Indian chaturanga or the Chinese xiang-qi; the third possibility, on the other hand, recognizes the existence of a syncretic civilizing effort, postulating a confluence of practices from different civilizations.

Beyond the validity of this trio of hypotheses, which are often each seen as independent efforts, we believe that an effort can be made to integrate the perspectives.

All the theories present elements that can be interconnected, in their complementarity, leaving aside, or perhaps reinterpreting, the divergences between them. The fact that the different variants of proto-chess have emerged in a wide but interconnected geographical space, and that this has happened in temporal synchrony, gives strong clues to a fact that we believe is incontrovertible: we are in the presence of a single family of games, with interconnected processes of evolution, which have yet to be fully discerned.

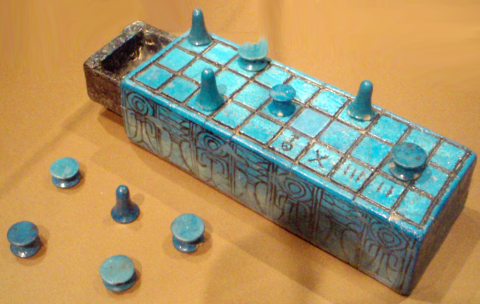

By extending the analysis, it would be possible to trace not only the interrelationship of the various proto-chess variants but also their origins in even older games. We could even go back to the Egyptian senet and, reconstructing the sequence from there on, arrive at chess as it was redefined in medieval Europe.

Under these conditions, it would be possible to work no longer from univocal, fragmented perspectives, but rather by proposing a holistic theory, integrating the evidence of each singular hypothesis, in such a way as to construct a unique, all-encompassing explanation.

Thus, instead of giving pre-eminence to chaturanga or xiang-qi an initial prototypes, it could be believed that at least one game appeared on the Silk Road from which these were derived, either concomitantly or sequentially. Therefore, in that case, the former would not derive from ashtāpada and the latter from liubo — rather, these earlier games, probably together with the Greek petteia and with the contribution of an ancient Babylonian astrolabe, produced a variant of proto-chess via cultural syncretism. This game, from then on, would expand through different routes, to the East and to the West.

So there are very interesting lines of exploration still to be developed. Although the possibility of testimonials appearing from ancient manuscripts on the subject is increasingly remote (although not entirely impossible), there could appear new archaeological findings that provide new clues, particularly in regard to the dating of games’ vestiges, which could better establish interrelationships and sequential information about these practices.

It is also possible, and indeed necessary, to continue to deepen structural analyses, based on the intrinsic characteristics and aetiology of the various games, in order to determine more precisely their correlation according to historical, geographical and cultural variables. This question is central to the design of the common evolutionary tree discussed above.

In any case, it is necessary to deepen the understanding of the practices that would have served as inputs of the proto-chess — petteia, liubo, ashtāpada — so that it will be possible to evaluate with more certainty, from the study of their particularities, the degree in which they could have had an effect in the subsequent modalities: xiang-qi and chaturanga.

Master Class Vol.4: José Raúl Capablanca

He was a child prodigy and he is surrounded by legends. In his best times he was considered to be unbeatable and by many he was reckoned to be the greatest chess talent of all time: Jose Raul Capablanca, born 1888 in Havana.

A ‘senet’ board that may correspond to the 14th century B.C.

In short, where did chess originate and under what circumstances?

We could simply reproduce some well-known legendary stories, such as the ones that attribute the invention of the game to Sissa the Wise or the queen of Lanka — or even to the battle in which a sovereign lost one of her sons in confrontation with his brother.

We could focus on divinities, on the esoteric world or on fictional literature.

We could, without analysing the whole, but observing only the parts, attribute the creation of the game to Indians, Chinese or other culture.

We could say, so as not to be mistaken, although falling into an obvious imprecision — which we can only admit in poetry — that chess appeared at a distant moment in time somewhere in the East.

What I said at the beginning. The restless Humanity wants to know everything. We will never be satisfied with simple and insufficient explanations; and less so with inaccurate ones.

A holistic theory about the origin of chess can perhaps help explain the steps that were taken for the emergence of the most influential and metaphorical game ever conceived.

In any case, we believe we are closer to discovering the key that will allow us to determine the initiating moment when the game appeared. And, from that, determine with much greater certainty how the whole sequence of subsequent diffusion took place.

For now, it might be better not to know everything yet.

Thus, there is a powerful incentive to further research this topic.

In this way, a suggestive and primordial mystery continues to haunt us: when did the magical and millenary game of chess appeared on Earth.

The ‘Origins of chess’ series

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: India

- Part 3: China

- Part 4: Egypt

- Part 5: Myths, legends

- Part 6: Cultural syncretism

Sunday, September 13, 2020

Sunday, September 6, 2020

Saturday, September 5, 2020

Englund Gambit: Harshavardhan v. Moskalenko, 1/2, 2020.08.25

[Site "https://lichess.org/40SaQnoA"]

[Date "2020.08.25"]

[Round "8"]

[White "Harshavardhan,G B (2397)"]

[Black "Moskalenko,A (2515)"]

[Result "1/2-1/2"]

[WhiteElo "?"]

[BlackElo "?"]

[Variant "Standard"]

[TimeControl "-"]

[ECO "A40"]

[Opening "Queen's Pawn Game: Englund Gambit"]

[Termination "Normal"]

[Annotator "lichess.org"]

1. d4 e5 2. dxe5 Nc6 3. Nf3 Qe7 4. Qd5 f6 5. exf6 Nxf6 { A40 Queen's Pawn Game: Englund Gambit } 6. Qd1 d5 7. Nc3 Be6 8. e3 O-O-O 9. Bb5 Qc5 10. Nd4 Bg4 11. f3 Bd7 12. Nxc6 Bxc6 13. Qd4 Bxb5 14. Qxc5 Bxc5 15. Nxb5 Rde8 16. O-O Bxe3+ 17. Bxe3 Rxe3 18. Nxa7+ Kd7 19. Nb5 c5 20. Rfe1 Rhe8 21. Rxe3 Rxe3 22. Kf2 d4 23. b4 cxb4 24. Nxd4 Ra3 25. Nb3 Nd5 26. Ke2 Nf4+ 27. Kd2 Nxg2 28. Rg1 Nh4 29. Rxg7+ Kc8 30. Rxh7 Nxf3+ 31. Ke3 Ne5 32. Kd4 Nc6+ 33. Kc5 Rxa2 34. Kd6 Kb8 35. Nc5 Na5 36. Nb3 Nc4+ 37. Kc5 Rxc2 38. Kxb4 Ne5 39. h4 Ka7 40. Nc5 Nc6+ 41. Kb5 Nd4+ 42. Kb4 Nc6+ 43. Kb5 Rb2+ 44. Kc4 Kb8 45. h5 Rc2+ 46. Kd5 Rd2+ 47. Ke4 Rd4+ 48. Ke3 Rh4 49. Rxb7+ Kc8 50. Rh7 Ne5 51. Ne4 Kd8 52. Nf6 Ng4+ 53. Nxg4 Rxg4 54. Kf3 Rh4 55. Kg3 Rh1 56. Kg4 Ke8 57. Kg5 Rg1+ 58. Kh6 Kf8 59. Ra7 Kg8 60. Ra8+ Kf7 61. Kh7 Rh1 62. h6 Rg1 63. Ra7+ Kf8 64. Rg7 Rh1 65. Rg2 Rf1 66. Re2 Rg1 67. Rf2+ Ke7 68. Rf5 Rg2 69. Ra5 Kf7 70. Ra7+ Kf8 71. Rg7 Rh2 72. Rg5 Rf2 73. Kh8 Rf1 74. Rg7 Rh1 75. Kh7 Rh2 76. Ra7 Rg2 77. Ra6 Kf7 78. Ra5 Rg1 79. Ra3 Kf8 80. Rf3+ Ke7 81. Kh8 Ke8 82. h7 Ke7 83. Ra3 Kf7 84. Ra8 Rg2 85. Rg8 Ra2 86. Rg7+ Kf8 87. Rg3 Rf2 88. Rg4 Rf1 89. Rg8+ Kf7 90. Rg7+ Kf8 91. Rg5 Rf2 92. Rg3 Rf1 93. Rg2 Rf3 94. Re2 Rg3 95. Ra2 Kf7 96. Ra7+ Kf8 97. Rb7 Rg1 98. Rb8+ Kf7 99. Rg8 Rh1 100. Rg3 Rf1 101. Rh3 Kf8 102. Rh2 Rf3 103. Rb2 Rf1 104. Rb8+ Kf7 105. Rb7+ Kf8 106. Rg7 Rh1 107. Rg4 Rf1 108. Rg3 Rf2 109. Rc3 Rf1 110. Rc8+ Kf7 111. Rg8 Rf2 112. Rg3 Rf1 113. Rg2 Rf3 114. Ra2 Kf8 115. Ra7 Rg3 116. Ra8+ Kf7 117. Ra7+ Kf8 { The game is a draw. } 1/2-1/2

Englund Gambit, Matta v. Efremova 0-1 , 2020.08.25

[Event "Titled Tue 25th Aug"]

[Site "https://lichess.org/lBRFdInO"]

[Date "2020.08.25"]

[Round "6"]

[White "Matta,Nicholas (2177)"]

[Black "Efremova,Y (2128)"]

[Result "0-1"]

[WhiteElo "?"]

[BlackElo "?"]

[Variant "Standard"]

[TimeControl "-"]

[ECO "A40"]

[Opening "Englund Gambit Complex: Englund Gambit"]

[Termination "Normal"]

[Annotator "lichess.org"]

1. d4 e5 2. dxe5 Nc6 3. Nf3 Qe7 { A40 Englund Gambit Complex: Englund Gambit } 4. Bf4 Qb4+ 5. Bd2 Qxb2 6. Nc3 Bb4 7. Rb1 Qa3 8. Nd5 Bxd2+ 9. Qxd2 Kd8 10. Qg5+ Nge7 11. Qxg7 Rg8 12. Qxf7 Qa5+ 13. c3 Qxd5 14. Qxh7 Nxe5 15. Rd1 Nxf3+ 16. exf3 Qe5+ 17. Be2 Qxc3+ 18. Kf1 Qg7 19. Qxg7 Rxg7 20. h4 d6 21. g4 Be6 22. h5 Bxa2 23. h6 Rg8 24. h7 Rh8 25. f4 Kd7 26. Bd3 Raf8 27. f5 Rf7 28. f6 Rxf6 29. g5 Re6 30. f4 Bd5 31. Rg1 Be4 32. g6 Bxd3+ 33. Rxd3 Rxg6 34. Rh1 Rg7 35. Rdh3 Rf7 36. Rh4 Ng6 37. Rh6 Nxf4 38. Ke1 { White resigns. } 0-1

Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit: Yordanov v. Milovic, 1-0, 2020.05.30

[Event "Euro Online +2300 Day 2"]

[Site "https://lichess.org/44rL2yKb"]

[Date "2020.05.30"]

[Round "2"]

[White "Yordanov,Lachezar (2307)"]

[Black "Milovic,J (2256)"]

[Result "1-0"]

[WhiteElo "2307"]

[BlackElo "2256"]

[Variant "Standard"]

[TimeControl "-"]

[ECO "A40"]

[Opening "Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit"]

[Termination "Normal"]

[Annotator "lichess.org"]

1. d4 { [%eval 0.0] } 1... e5?? { (0.00 → 1.57) Blunder. Nf6 was best. } { [%eval 1.57] } (1... Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 d5 4. cxd5 exd5 5. Bf4 c6 6. Nc3) 2. dxe5 { [%eval 0.79] } 2... d6 { [%eval 1.4] } { A40 Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit } 3. Nf3 { [%eval 1.27] } 3... Bg4 { [%eval 1.63] } 4. exd6 { [%eval 1.16] } 4... Bxd6 { [%eval 1.39] } 5. Qd4 { [%eval 1.22] } 5... Nf6 { [%eval 1.09] } 6. Bg5 { [%eval 1.23] } 6... Nc6 { [%eval 1.19] } 7. Qe3+?! { (1.19 → 0.36) Inaccuracy. Qxg4 was best. } { [%eval 0.36] } (7. Qxg4 Nxg4 8. Bxd8 Rxd8 9. e3 Nb4 10. Na3 c6 11. Be2 O-O 12. c3 Nd3+ 13. Bxd3 Bxa3) 7... Be6 { [%eval 0.3] } 8. Nc3 { [%eval -0.16] } 8... Qe7?! { (-0.16 → 0.60) Inaccuracy. h6 was best. } { [%eval 0.6] } (8... h6 9. Bxf6 Qxf6 10. g3 O-O-O 11. O-O-O Qf5 12. Qe4 Qa5 13. Qa4 Qxa4 14. Nxa4 Bxa2 15. Bh3+) 9. O-O-O { [%eval 0.29] } 9... O-O-O { [%eval 0.61] } 10. Ne4 { [%eval 0.21] } 10... Rhe8? { (0.21 → 1.33) Mistake. Bb4 was best. } { [%eval 1.33] } (10... Bb4 11. Nd4 Nxd4 12. Rxd4 Ba5 13. Rd3 Qb4 14. Nc3 Rxd3 15. exd3 Bb6 16. Qd2 Rd8 17. Be3) 11. Nxd6+?! { (1.33 → 0.58) Inaccuracy. a3 was best. } { [%eval 0.58] } (11. a3 h6 12. Bxf6 gxf6 13. g3 Be5 14. Rxd8+ Qxd8 15. Qc5 Qd5 16. Qxd5 Bxd5 17. Ned2 Nd4) 11... Rxd6 { [%eval 0.5] } 12. Rxd6 { [%eval 0.0] } 12... Qxd6 { [%eval 0.0] } 13. Bxf6 { [%eval 0.0] } 13... gxf6 { [%eval 0.0] } 14. Qd2 { [%eval 0.0] } 14... Qc5 { [%eval 0.0] } 15. e3 { [%eval 0.0] } 15... Bxa2 { [%eval 0.1] } 16. Bd3 { [%eval -0.33] } 16... Be6 { [%eval -0.19] } 17. Qc3 { [%eval -0.29] } 17... Qxc3 { [%eval -0.19] } 18. bxc3 { [%eval 0.1] } 18... Ne5? { (0.10 → 1.21) Mistake. h6 was best. } { [%eval 1.21] } (18... h6 19. Kb2) 19. Nd4? { (1.21 → -0.30) Mistake. Nxe5 was best. } { [%eval -0.3] } (19. Nxe5 fxe5 20. Bxh7 Rh8 21. Bd3 f5 22. h4 e4 23. Be2 Kd7 24. Kb2 Kd6 25. h5 Rh6) 19... c5 { [%eval -0.1] } 20. Nb5 { [%eval -0.52] } 20... Rd8 { [%eval -0.65] } 21. Nxa7+ { [%eval -0.81] } 21... Kb8?! { (-0.81 → 0.00) Inaccuracy. Kc7 was best. } { [%eval 0.0] } (21... Kc7 22. Nb5+ Kb6 23. Na3 Nxd3+ 24. cxd3 Rxd3 25. Nb1 Bb3 26. Kb2 Ba4 27. e4 Kc6 28. Re1) 22. Nb5 { [%eval 0.0] } 22... Nxd3+ { [%eval 0.0] } 23. cxd3 { [%eval 0.0] } 23... Rxd3 { [%eval 0.0] } 24. Rd1 { [%eval 0.0] } 24... Rxd1+ { [%eval 0.1] } 25. Kxd1 { [%eval 0.61] } 25... Kc8?! { (0.61 → 1.38) Inaccuracy. Bd7 was best. } { [%eval 1.38] } (25... Bd7 26. Nd6) 26. Nd6+ { [%eval 1.26] } 26... Kc7 { [%eval 1.36] } 27. Ne8+ { [%eval 1.28] } 27... Kc6? { (1.28 → 2.81) Mistake. Kd8 was best. } { [%eval 2.81] } (27... Kd8 28. Nxf6) 28. Nxf6 { [%eval 2.72] } 28... h6 { [%eval 2.89] } 29. h4? { (2.89 → 1.43) Mistake. g4 was best. } { [%eval 1.43] } (29. g4 Kd6 30. f4 Bd7 31. e4 b5 32. e5+ Ke7 33. f5 b4 34. Ng8+ Kf8 35. Nxh6 Ba4+) 29... b5? { (1.43 → 3.00) Mistake. Kd6 was best. } { [%eval 3.0] } (29... Kd6 30. g4) 30. g4 { [%eval 2.62] } 30... b4? { (2.62 → 4.51) Mistake. Kd6 was best. } { [%eval 4.51] } (30... Kd6 31. f4) 31. cxb4 { [%eval 4.34] } 31... cxb4 { [%eval 4.27] } 32. g5 { [%eval 4.2] } 32... hxg5 { [%eval 3.97] } 33. h5 { [%eval 3.65] } 33... b3?? { (3.65 → 10.98) Blunder. Kd6 was best. } { [%eval 10.98] } (33... Kd6 34. h6) 34. e4 { [%eval 9.45] } 34... Kc5 { [%eval 11.06] } 35. Kc1 { [%eval 11.15] } 35... Kd4 { [%eval 14.0] } 36. h6 { [%eval 10.32] } 36... Kc3 { [%eval 23.2] } 37. Nd5+ { [%eval 18.03] } 37... Kd4 { [%eval 60.87] } 38. h7 { [%eval 17.1] } 38... Kxe4 { [%eval 17.14] } 39. Nc3+ { [%eval 14.47] } { Black resigns. } 1-0

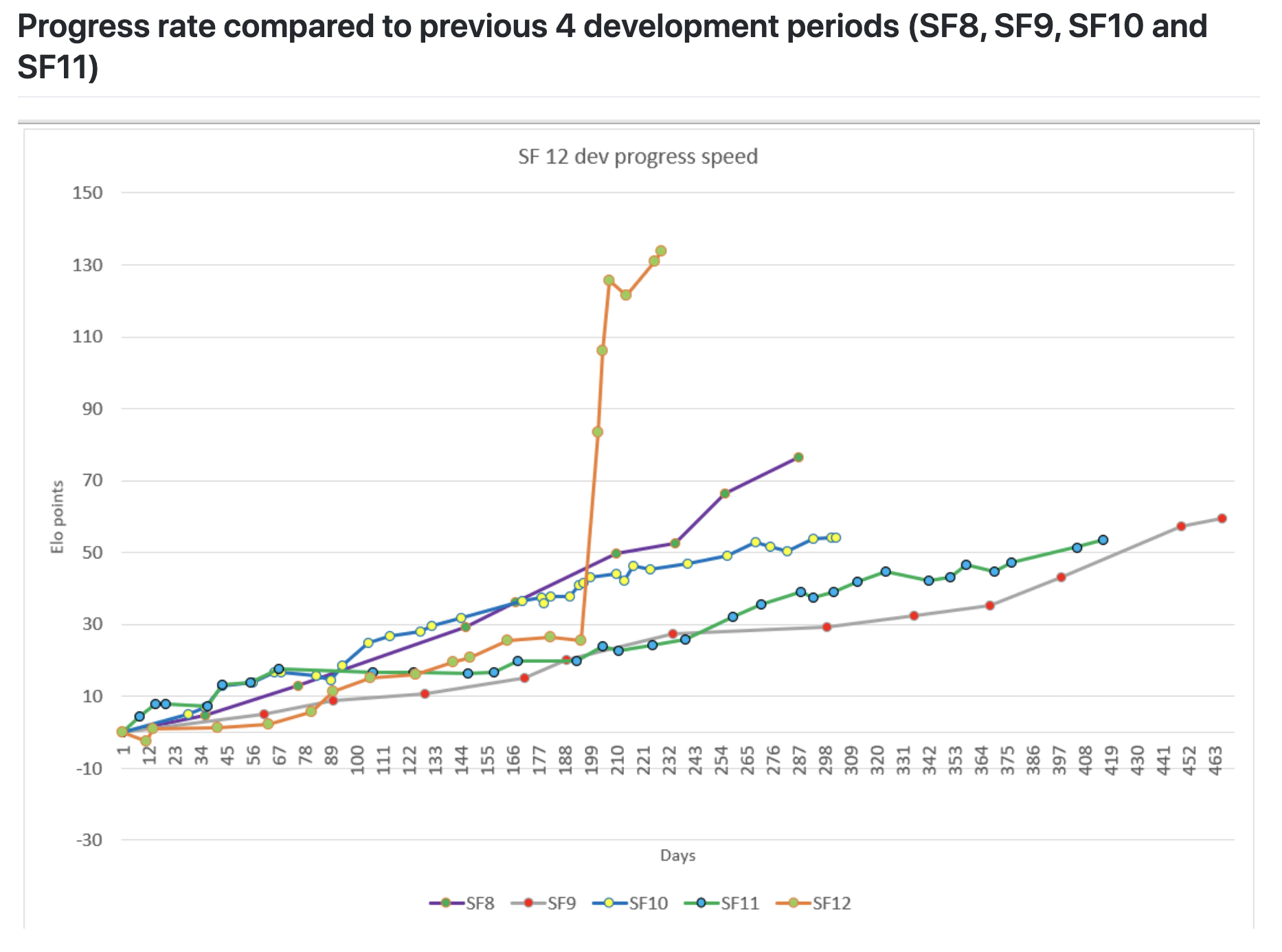

Stockfish 12 Released, 130 Elo Points Stronger

Stockfish 12 Released, 130 Elo Points Stronger

Version 12 of the popular open-source chess engine Stockfish was released on Thursday. It is a major update that includes an efficiently updatable neural network and is significantly stronger than earlier versions.

According to the official Stockfish blog, version 12 of Stockfish plays significantly stronger than any of its predecessors: "In a match against Stockfish 11, Stockfish 12 will typically win at least 10 times more game pairs than it loses."

The rating difference compared to Stockfish 11 is estimated to be about 130 Elo points. This became clear from internal progression tests during development and was recently confirmed In Chess.com's computer chess environment where Stockfish+NNUE and Leela Chess Zero performed quite comparably.

Stockfish 12 combines the brute-force computing approach of traditional Stockfish with the advanced evaluation capabilities of neural network chess engines such as AlphaZero and Leela Chess Zero.

In the new version, two evaluation functions are available. Besides the classical evaluation function, there is now the NNUE evaluation which is computed with a neural network based on basic inputs. The network is optimized and trained on the evaluations of millions of positions.

German Chess Magazine #1979

One early user wrote on Reddit: "From personal experience, Stockfish 12’s positional understanding is really unlike anything before it. Even Leela on extremely powerful hardware can seem blind to Stockfish 12’s search. Pretty much every major blindspot, like pawn structure weaknesses, seems gone in this new evaluation."

Stockfish 12 is available for download here with the neural network already embedded and ready to go. Chess.com expects to soon have Stockfish 12 available in our "max analysis" feature.

See also:

Friday, September 4, 2020

Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit

[Site "https://lichess.org/DmP4bcSE"]

[Date "2020.09.03"]

[White "Kung_Fu_Panda3"]

[Black "MoneyDoctor"]

[Result "0-1"]

[UTCDate "2020.09.03"]

[UTCTime "18:15:25"]

[WhiteElo "2433"]

[BlackElo "2018"]

[WhiteRatingDiff "-10"]

[BlackRatingDiff "+11"]

[Variant "Standard"]

[TimeControl "600+0"]

[ECO "A40"]

[Opening "Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit"]

[Termination "Normal"]

[Annotator "lichess.org"]

1. d4 e5?? { (0.00 → 1.57) Blunder. Nf6 was best. } (1... Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 d5 4. cxd5 exd5 5. Bf4 c6 6. Nc3) 2. dxe5 d6 { A40 Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit } 3. Nf3 Bg4 4. Qd4 Qd7 5. Nc3?! { (1.27 → 0.69) Inaccuracy. exd6 was best. } (5. exd6 Nc6 6. Qe3+ Be6 7. dxc7 Nf6 8. Nc3 Qxc7 9. a3 Rd8 10. Qg5 Ng4 11. h3 Be7) 5... Nc6 6. Qe4 Bxf3 7. exf3 dxe5 8. Bb5 Nge7?! { (0.56 → 1.27) Inaccuracy. Bd6 was best. } (8... Bd6 9. Bxc6 Qxc6 10. Qxc6+ bxc6 11. Ne4 f5 12. Nd2 Nf6 13. Nc4 e4 14. fxe4 Nxe4 15. f3) 9. Be3 a6 10. Rd1 Qxd1+?? { (1.51 → 4.91) Blunder. Qe6 was best. } (10... Qe6 11. Ba4) 11. Kxd1 axb5 12. Nxb5 O-O-O+ 13. Ke2 f5 14. Qa4 f4?! { (4.52 → 6.90) Inaccuracy. Kb8 was best. } (14... Kb8) 15. Bc5? { (6.90 → 4.13) Mistake. Qa8+ was best. } (15. Qa8+ Kd7 16. Qxb7 fxe3 17. fxe3 g5 18. Rd1+ Ke6 19. Nxc7+ Kf6 20. Nd5+ Nxd5 21. Qxc6+ Rd6) 15... Nd5 16. Qa8+ Kd7 17. Qxb7?? { (4.21 → 0.85) Blunder. Qa3 was best. } (17. Qa3 Kc8 18. Bxf8 Rhxf8 19. Rd1 Nb6 20. Rxd8+ Rxd8 21. Na7+ Nxa7 22. Qxa7 Rd6 23. Qa3 Kb8) 17... Bxc5? { (0.85 → 2.35) Mistake. Rb8 was best. } (17... Rb8 18. Qa6) 18. Rd1 Bd4 19. Na7?? { (2.12 → -1.42) Blunder. Nxd4 was best. } (19. Nxd4) 19... Nce7 20. Qb5+ Ke6 21. Nc6 Nxc6 22. Qxc6+ Rd6 23. Qc4?! { (-1.34 → -2.45) Inaccuracy. Qb5 was best. } (23. Qb5 Rhd8 24. c4 Ne7 25. Qb3 Ra6 26. a4 Rda8 27. Qc2 Rxa4 28. Rxd4 exd4 29. Qe4+ Kf7) 23... Rb8 24. Rxd4 exd4 25. Qxd4?! { (-3.06 → -3.93) Inaccuracy. b3 was best. } (25. b3 Re8) 25... Rb4?? { (-3.93 → -0.44) Blunder. Kf7 was best. } (25... Kf7) 26. Qxg7 Nf6 27. b3?? { (-0.14 → -14.63) Blunder. Qxc7 was best. } (27. Qxc7) 27... Rbd4 28. g3 Rd1 { White resigns. } 0-1

Monday, August 31, 2020

Thursday, August 27, 2020

Tuesday, August 25, 2020

Saturday, August 22, 2020

Thursday, August 20, 2020

Saturday, August 15, 2020

How to defeat online chess cheating - once and for all

by Marco Saba, August 15, 2020 (Italian translation below the text)

To understand this document you must be well versed in chess, psychology and intelligence. And you must know an online chess system, like lichess.org pictured above.

A classic cheater on lichess:

How could one discourage these antisocial cheats?

To this unresolved chess problem, I propose this solution: it is not enough to reintegrate the victim of the points he lost because of the undeserved defeat, it must be adequately compensated. Since the penalty for the cheater is the loss of the score obtained and expulsion from the system, and it is known that he uses programs that have the score of 3300 ELO points, you should compensate the victim by giving him the score as if he had WON a game against a 3300 opponent. For example, for a 2000 ELO points player who lost 5 points, you would have to reinstate the points lost AND ADD THE POINTS AS IF YOU WON !

That is, in the case of a 2000 ELO player cheated by the 3300 ELO program, you would have an increase of + 32 ELO (http://www.ewbilliards.com/EloCalculater/), so it would go up to 2032, instead of simply being reinstated to 2000. This system would discourage the only goal that cheaters manage to achieve: to keep the ELO of honest players artificially low. And it would avoid that many players decide to abandon lichess.org as an online gaming platform for good because it's too frustrating to always lose with a player-program that even if it shows a low score (from 1300 to 1700) actually has such a high actual score (3300) when the human chess world champion only reaches 2900 !

It is necessary to frustrate sadistic predators and reward honest players, this is the only way to make sure that everyone plays with satisfaction seeing the deserved progress they make.

It only takes one or two cheaters per tournament to lose the desire to play chess online. It's a shame not to use a bit of psychology to identify and eliminate cheaters who want to do nothing but harm others, because they are not capable of doing any good.

A similar system should also be imagined for other situations, for example the bank credit cartel. But I will discuss this in another blog dedicated to economics and monetary sovereignty, where for example I easily deciphered the "miracle" of Norway by simply reading their banking law: