Monday, September 28, 2020

Tuesday, September 22, 2020

On the origins of chess

On the origins of chess (7/7)

Find the right combination! ChessBase 15 program + new Mega Database 2020 with 8 million games and more than 80,000 master analyses. Plus ChessBase Magazine (DVD + magazine) and CB Premium membership for 1 year!

1: Introduction | 2: India | 3: China | 4: Egypt | 5: Myths, legends | 6: Cultural syncretism

Part 7: Epilogue

At this point of the investigations on the origin of chess there are things we know, things we suppose we know and things that we ignore. Let’s list them one by one:

We know that the game arose in the Orient.

We know that there are only three theories that present valid sources to support their stance on the original source of the game: the one that locates the origin in India; the one that focuses on China, and that of cultural syncretism.

We know that a variant of proto-chess entered Persia in the sixth century AD coming from a region of India.

We suppose that this game was chaturanga, in its two-player modality, which was taken to present-day Baghdad, the capital of the Persian Empire.

We know that the first precise mentions to a variant of proto-chess, coming from diverse literary sources, appear in the fourth century AD, the first of which refers to the Chinese xiang-qi and the second one to chaturanga.

We know that both xiang-qi and chaturanga had their respective transformation processes.

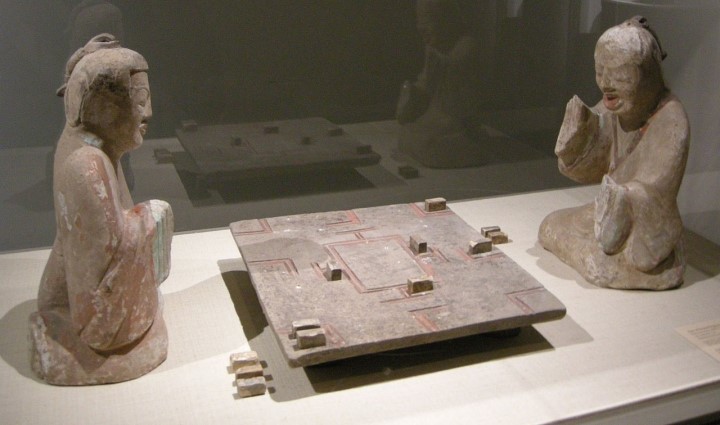

We know that there are two previous games that were born in these cultures, which had been recorded in literary works since ancient times: the Chinese liubo and the Indian ashtāpada.

We suppose that xiang-qi — if it came exclusively from the Chinese culture — could have been conceived from liubo.

We suppose that chaturanga — if it came exclusively from the Indian culture — could have been conceived from ashtāpada or chaturaji.

We ignore the sequence in which chaturaji and chaturanga came to be (although the predominant theory is that the latter came first), or even if chaturaji is a mere position of chaturanga.

We know that a version of xiang-qi has survived to the present day (it is currently played in China and, at least, also in Vietnam) while chaturanga disappeared as a practice at some distant moment in time.

We ignore under which precise circumstances chaturanga abandoned the use of dice.

We ignore whether the evolutionary process of chaturanga went from the four-player version to the two-player one or the other way around.

We suppose that a synthesis of several previous games was generated on the Silk Route, appearing a new prototype that later turned into chess.

We ignore if, at the end of that process, only one game arose or, if on the contrary, both chaturanga and xiang-qi appeared simultaneously.

We suppose that the games that were part of the process of cultural syncretism were liubo, ashtāpada and the Greek petteia, and possibly the process took place under the influence of an old astrolabe of Babylonian origin.

We suppose that this symbiosis occurred in a period of time between the second century BC and the third century AD.

We suppose that the process took place in a vast region occupied successively by the Kingdom of Bactria and the Kushán Empire

We know that the oldest archaeological findings of pieces that were used in some variant of proto-chess — which correlate perfectly with the geographical zones linked to the Silk Route — existed approximately in the sixth century AD.

We suppose that in the future other important archaeological elements will be discovered that, depending on their location, characteristics and antiquity, will strengthen our knowledge regarding this matter.

We know that it is necessary to deepen the analysis with regard to the theory of games, establishing greater precision and causal relationships between the various variants of proto-chess and linked practices — namely ashtāpada, chaturanga, chaturaji, liubo, xiang-qi, petteia and others.

We know that there is much yet to be investigated on the origin of chess.

We suppose that we will eventually find an answer that, without becoming an absolute certainty, at least will allow us to find a major consensus, thus establishing a uniform explanatory paradigm on the origin of chess.

Master Class Vol.9: Paul Morphy

Learn about one of the greatest geniuses in the history of chess! Paul Morphy's career (1837-1884) lasted only a few years and yet he managed to defeat the best chess players of his time.

Statuettes probably from the first to the second century of the Christian era representing two players disputing a game of liubo. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Epilogue

Chess might be the product of a cooperative process — and we would prefer it to be this way, to show that Humanity has the capacity to be virtuous at times (although it is known that it usually favours quarrels, often bloody, between people who seem to forget that they come from a common origin). The game could also have been an invention/creation/discovery of a single culture. Anyway, there is only one thing that is entirely certain: as Borges correctly pointed out, chess comes from the East.

In that sense, we have presented the different protohistoric versions regarding the origins of the game, focusing on that geographical space (India, China, Persia and other undetermined spots within the Silk Road), with physical or literary records that refer to a few centuries before and after the arrival of Christ.

There are quite exact records of many specific episodes, such as the time when one of the versions of the game entered Ctesifonte from India, which happened exactly in the sixth century AD. From that moment on, everything is quite clear, in terms of the diffusion of chess; before this event, however, everything is much less clear.

In this context of uncertainty, there are conflicting theses on the origin of chess, some of which have empirical support while others can only be recognized as myths or legends. All of them, with the inevitable omissions born out of the vastness of the analytical field, were compiled in this work.

After all, there are mainly three possibilities with a high degree of truthfulness and verisimilitude: two of them correspond to particular cultures — those that consider that chess comes from the Indian chaturanga or the Chinese xiang-qi; the third possibility, on the other hand, recognizes the existence of a syncretic civilizing effort, postulating a confluence of practices from different civilizations.

Beyond the validity of this trio of hypotheses, which are often each seen as independent efforts, we believe that an effort can be made to integrate the perspectives.

All the theories present elements that can be interconnected, in their complementarity, leaving aside, or perhaps reinterpreting, the divergences between them. The fact that the different variants of proto-chess have emerged in a wide but interconnected geographical space, and that this has happened in temporal synchrony, gives strong clues to a fact that we believe is incontrovertible: we are in the presence of a single family of games, with interconnected processes of evolution, which have yet to be fully discerned.

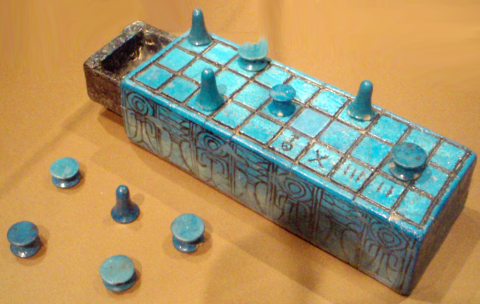

By extending the analysis, it would be possible to trace not only the interrelationship of the various proto-chess variants but also their origins in even older games. We could even go back to the Egyptian senet and, reconstructing the sequence from there on, arrive at chess as it was redefined in medieval Europe.

Under these conditions, it would be possible to work no longer from univocal, fragmented perspectives, but rather by proposing a holistic theory, integrating the evidence of each singular hypothesis, in such a way as to construct a unique, all-encompassing explanation.

Thus, instead of giving pre-eminence to chaturanga or xiang-qi an initial prototypes, it could be believed that at least one game appeared on the Silk Road from which these were derived, either concomitantly or sequentially. Therefore, in that case, the former would not derive from ashtāpada and the latter from liubo — rather, these earlier games, probably together with the Greek petteia and with the contribution of an ancient Babylonian astrolabe, produced a variant of proto-chess via cultural syncretism. This game, from then on, would expand through different routes, to the East and to the West.

So there are very interesting lines of exploration still to be developed. Although the possibility of testimonials appearing from ancient manuscripts on the subject is increasingly remote (although not entirely impossible), there could appear new archaeological findings that provide new clues, particularly in regard to the dating of games’ vestiges, which could better establish interrelationships and sequential information about these practices.

It is also possible, and indeed necessary, to continue to deepen structural analyses, based on the intrinsic characteristics and aetiology of the various games, in order to determine more precisely their correlation according to historical, geographical and cultural variables. This question is central to the design of the common evolutionary tree discussed above.

In any case, it is necessary to deepen the understanding of the practices that would have served as inputs of the proto-chess — petteia, liubo, ashtāpada — so that it will be possible to evaluate with more certainty, from the study of their particularities, the degree in which they could have had an effect in the subsequent modalities: xiang-qi and chaturanga.

Master Class Vol.4: José Raúl Capablanca

He was a child prodigy and he is surrounded by legends. In his best times he was considered to be unbeatable and by many he was reckoned to be the greatest chess talent of all time: Jose Raul Capablanca, born 1888 in Havana.

A ‘senet’ board that may correspond to the 14th century B.C.

In short, where did chess originate and under what circumstances?

We could simply reproduce some well-known legendary stories, such as the ones that attribute the invention of the game to Sissa the Wise or the queen of Lanka — or even to the battle in which a sovereign lost one of her sons in confrontation with his brother.

We could focus on divinities, on the esoteric world or on fictional literature.

We could, without analysing the whole, but observing only the parts, attribute the creation of the game to Indians, Chinese or other culture.

We could say, so as not to be mistaken, although falling into an obvious imprecision — which we can only admit in poetry — that chess appeared at a distant moment in time somewhere in the East.

What I said at the beginning. The restless Humanity wants to know everything. We will never be satisfied with simple and insufficient explanations; and less so with inaccurate ones.

A holistic theory about the origin of chess can perhaps help explain the steps that were taken for the emergence of the most influential and metaphorical game ever conceived.

In any case, we believe we are closer to discovering the key that will allow us to determine the initiating moment when the game appeared. And, from that, determine with much greater certainty how the whole sequence of subsequent diffusion took place.

For now, it might be better not to know everything yet.

Thus, there is a powerful incentive to further research this topic.

In this way, a suggestive and primordial mystery continues to haunt us: when did the magical and millenary game of chess appeared on Earth.

The ‘Origins of chess’ series

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: India

- Part 3: China

- Part 4: Egypt

- Part 5: Myths, legends

- Part 6: Cultural syncretism

Sunday, September 13, 2020

Sunday, September 6, 2020

Saturday, September 5, 2020

Englund Gambit: Harshavardhan v. Moskalenko, 1/2, 2020.08.25

[Site "https://lichess.org/40SaQnoA"]

[Date "2020.08.25"]

[Round "8"]

[White "Harshavardhan,G B (2397)"]

[Black "Moskalenko,A (2515)"]

[Result "1/2-1/2"]

[WhiteElo "?"]

[BlackElo "?"]

[Variant "Standard"]

[TimeControl "-"]

[ECO "A40"]

[Opening "Queen's Pawn Game: Englund Gambit"]

[Termination "Normal"]

[Annotator "lichess.org"]

1. d4 e5 2. dxe5 Nc6 3. Nf3 Qe7 4. Qd5 f6 5. exf6 Nxf6 { A40 Queen's Pawn Game: Englund Gambit } 6. Qd1 d5 7. Nc3 Be6 8. e3 O-O-O 9. Bb5 Qc5 10. Nd4 Bg4 11. f3 Bd7 12. Nxc6 Bxc6 13. Qd4 Bxb5 14. Qxc5 Bxc5 15. Nxb5 Rde8 16. O-O Bxe3+ 17. Bxe3 Rxe3 18. Nxa7+ Kd7 19. Nb5 c5 20. Rfe1 Rhe8 21. Rxe3 Rxe3 22. Kf2 d4 23. b4 cxb4 24. Nxd4 Ra3 25. Nb3 Nd5 26. Ke2 Nf4+ 27. Kd2 Nxg2 28. Rg1 Nh4 29. Rxg7+ Kc8 30. Rxh7 Nxf3+ 31. Ke3 Ne5 32. Kd4 Nc6+ 33. Kc5 Rxa2 34. Kd6 Kb8 35. Nc5 Na5 36. Nb3 Nc4+ 37. Kc5 Rxc2 38. Kxb4 Ne5 39. h4 Ka7 40. Nc5 Nc6+ 41. Kb5 Nd4+ 42. Kb4 Nc6+ 43. Kb5 Rb2+ 44. Kc4 Kb8 45. h5 Rc2+ 46. Kd5 Rd2+ 47. Ke4 Rd4+ 48. Ke3 Rh4 49. Rxb7+ Kc8 50. Rh7 Ne5 51. Ne4 Kd8 52. Nf6 Ng4+ 53. Nxg4 Rxg4 54. Kf3 Rh4 55. Kg3 Rh1 56. Kg4 Ke8 57. Kg5 Rg1+ 58. Kh6 Kf8 59. Ra7 Kg8 60. Ra8+ Kf7 61. Kh7 Rh1 62. h6 Rg1 63. Ra7+ Kf8 64. Rg7 Rh1 65. Rg2 Rf1 66. Re2 Rg1 67. Rf2+ Ke7 68. Rf5 Rg2 69. Ra5 Kf7 70. Ra7+ Kf8 71. Rg7 Rh2 72. Rg5 Rf2 73. Kh8 Rf1 74. Rg7 Rh1 75. Kh7 Rh2 76. Ra7 Rg2 77. Ra6 Kf7 78. Ra5 Rg1 79. Ra3 Kf8 80. Rf3+ Ke7 81. Kh8 Ke8 82. h7 Ke7 83. Ra3 Kf7 84. Ra8 Rg2 85. Rg8 Ra2 86. Rg7+ Kf8 87. Rg3 Rf2 88. Rg4 Rf1 89. Rg8+ Kf7 90. Rg7+ Kf8 91. Rg5 Rf2 92. Rg3 Rf1 93. Rg2 Rf3 94. Re2 Rg3 95. Ra2 Kf7 96. Ra7+ Kf8 97. Rb7 Rg1 98. Rb8+ Kf7 99. Rg8 Rh1 100. Rg3 Rf1 101. Rh3 Kf8 102. Rh2 Rf3 103. Rb2 Rf1 104. Rb8+ Kf7 105. Rb7+ Kf8 106. Rg7 Rh1 107. Rg4 Rf1 108. Rg3 Rf2 109. Rc3 Rf1 110. Rc8+ Kf7 111. Rg8 Rf2 112. Rg3 Rf1 113. Rg2 Rf3 114. Ra2 Kf8 115. Ra7 Rg3 116. Ra8+ Kf7 117. Ra7+ Kf8 { The game is a draw. } 1/2-1/2

Englund Gambit, Matta v. Efremova 0-1 , 2020.08.25

[Event "Titled Tue 25th Aug"]

[Site "https://lichess.org/lBRFdInO"]

[Date "2020.08.25"]

[Round "6"]

[White "Matta,Nicholas (2177)"]

[Black "Efremova,Y (2128)"]

[Result "0-1"]

[WhiteElo "?"]

[BlackElo "?"]

[Variant "Standard"]

[TimeControl "-"]

[ECO "A40"]

[Opening "Englund Gambit Complex: Englund Gambit"]

[Termination "Normal"]

[Annotator "lichess.org"]

1. d4 e5 2. dxe5 Nc6 3. Nf3 Qe7 { A40 Englund Gambit Complex: Englund Gambit } 4. Bf4 Qb4+ 5. Bd2 Qxb2 6. Nc3 Bb4 7. Rb1 Qa3 8. Nd5 Bxd2+ 9. Qxd2 Kd8 10. Qg5+ Nge7 11. Qxg7 Rg8 12. Qxf7 Qa5+ 13. c3 Qxd5 14. Qxh7 Nxe5 15. Rd1 Nxf3+ 16. exf3 Qe5+ 17. Be2 Qxc3+ 18. Kf1 Qg7 19. Qxg7 Rxg7 20. h4 d6 21. g4 Be6 22. h5 Bxa2 23. h6 Rg8 24. h7 Rh8 25. f4 Kd7 26. Bd3 Raf8 27. f5 Rf7 28. f6 Rxf6 29. g5 Re6 30. f4 Bd5 31. Rg1 Be4 32. g6 Bxd3+ 33. Rxd3 Rxg6 34. Rh1 Rg7 35. Rdh3 Rf7 36. Rh4 Ng6 37. Rh6 Nxf4 38. Ke1 { White resigns. } 0-1

Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit: Yordanov v. Milovic, 1-0, 2020.05.30

[Event "Euro Online +2300 Day 2"]

[Site "https://lichess.org/44rL2yKb"]

[Date "2020.05.30"]

[Round "2"]

[White "Yordanov,Lachezar (2307)"]

[Black "Milovic,J (2256)"]

[Result "1-0"]

[WhiteElo "2307"]

[BlackElo "2256"]

[Variant "Standard"]

[TimeControl "-"]

[ECO "A40"]

[Opening "Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit"]

[Termination "Normal"]

[Annotator "lichess.org"]

1. d4 { [%eval 0.0] } 1... e5?? { (0.00 → 1.57) Blunder. Nf6 was best. } { [%eval 1.57] } (1... Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 d5 4. cxd5 exd5 5. Bf4 c6 6. Nc3) 2. dxe5 { [%eval 0.79] } 2... d6 { [%eval 1.4] } { A40 Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit } 3. Nf3 { [%eval 1.27] } 3... Bg4 { [%eval 1.63] } 4. exd6 { [%eval 1.16] } 4... Bxd6 { [%eval 1.39] } 5. Qd4 { [%eval 1.22] } 5... Nf6 { [%eval 1.09] } 6. Bg5 { [%eval 1.23] } 6... Nc6 { [%eval 1.19] } 7. Qe3+?! { (1.19 → 0.36) Inaccuracy. Qxg4 was best. } { [%eval 0.36] } (7. Qxg4 Nxg4 8. Bxd8 Rxd8 9. e3 Nb4 10. Na3 c6 11. Be2 O-O 12. c3 Nd3+ 13. Bxd3 Bxa3) 7... Be6 { [%eval 0.3] } 8. Nc3 { [%eval -0.16] } 8... Qe7?! { (-0.16 → 0.60) Inaccuracy. h6 was best. } { [%eval 0.6] } (8... h6 9. Bxf6 Qxf6 10. g3 O-O-O 11. O-O-O Qf5 12. Qe4 Qa5 13. Qa4 Qxa4 14. Nxa4 Bxa2 15. Bh3+) 9. O-O-O { [%eval 0.29] } 9... O-O-O { [%eval 0.61] } 10. Ne4 { [%eval 0.21] } 10... Rhe8? { (0.21 → 1.33) Mistake. Bb4 was best. } { [%eval 1.33] } (10... Bb4 11. Nd4 Nxd4 12. Rxd4 Ba5 13. Rd3 Qb4 14. Nc3 Rxd3 15. exd3 Bb6 16. Qd2 Rd8 17. Be3) 11. Nxd6+?! { (1.33 → 0.58) Inaccuracy. a3 was best. } { [%eval 0.58] } (11. a3 h6 12. Bxf6 gxf6 13. g3 Be5 14. Rxd8+ Qxd8 15. Qc5 Qd5 16. Qxd5 Bxd5 17. Ned2 Nd4) 11... Rxd6 { [%eval 0.5] } 12. Rxd6 { [%eval 0.0] } 12... Qxd6 { [%eval 0.0] } 13. Bxf6 { [%eval 0.0] } 13... gxf6 { [%eval 0.0] } 14. Qd2 { [%eval 0.0] } 14... Qc5 { [%eval 0.0] } 15. e3 { [%eval 0.0] } 15... Bxa2 { [%eval 0.1] } 16. Bd3 { [%eval -0.33] } 16... Be6 { [%eval -0.19] } 17. Qc3 { [%eval -0.29] } 17... Qxc3 { [%eval -0.19] } 18. bxc3 { [%eval 0.1] } 18... Ne5? { (0.10 → 1.21) Mistake. h6 was best. } { [%eval 1.21] } (18... h6 19. Kb2) 19. Nd4? { (1.21 → -0.30) Mistake. Nxe5 was best. } { [%eval -0.3] } (19. Nxe5 fxe5 20. Bxh7 Rh8 21. Bd3 f5 22. h4 e4 23. Be2 Kd7 24. Kb2 Kd6 25. h5 Rh6) 19... c5 { [%eval -0.1] } 20. Nb5 { [%eval -0.52] } 20... Rd8 { [%eval -0.65] } 21. Nxa7+ { [%eval -0.81] } 21... Kb8?! { (-0.81 → 0.00) Inaccuracy. Kc7 was best. } { [%eval 0.0] } (21... Kc7 22. Nb5+ Kb6 23. Na3 Nxd3+ 24. cxd3 Rxd3 25. Nb1 Bb3 26. Kb2 Ba4 27. e4 Kc6 28. Re1) 22. Nb5 { [%eval 0.0] } 22... Nxd3+ { [%eval 0.0] } 23. cxd3 { [%eval 0.0] } 23... Rxd3 { [%eval 0.0] } 24. Rd1 { [%eval 0.0] } 24... Rxd1+ { [%eval 0.1] } 25. Kxd1 { [%eval 0.61] } 25... Kc8?! { (0.61 → 1.38) Inaccuracy. Bd7 was best. } { [%eval 1.38] } (25... Bd7 26. Nd6) 26. Nd6+ { [%eval 1.26] } 26... Kc7 { [%eval 1.36] } 27. Ne8+ { [%eval 1.28] } 27... Kc6? { (1.28 → 2.81) Mistake. Kd8 was best. } { [%eval 2.81] } (27... Kd8 28. Nxf6) 28. Nxf6 { [%eval 2.72] } 28... h6 { [%eval 2.89] } 29. h4? { (2.89 → 1.43) Mistake. g4 was best. } { [%eval 1.43] } (29. g4 Kd6 30. f4 Bd7 31. e4 b5 32. e5+ Ke7 33. f5 b4 34. Ng8+ Kf8 35. Nxh6 Ba4+) 29... b5? { (1.43 → 3.00) Mistake. Kd6 was best. } { [%eval 3.0] } (29... Kd6 30. g4) 30. g4 { [%eval 2.62] } 30... b4? { (2.62 → 4.51) Mistake. Kd6 was best. } { [%eval 4.51] } (30... Kd6 31. f4) 31. cxb4 { [%eval 4.34] } 31... cxb4 { [%eval 4.27] } 32. g5 { [%eval 4.2] } 32... hxg5 { [%eval 3.97] } 33. h5 { [%eval 3.65] } 33... b3?? { (3.65 → 10.98) Blunder. Kd6 was best. } { [%eval 10.98] } (33... Kd6 34. h6) 34. e4 { [%eval 9.45] } 34... Kc5 { [%eval 11.06] } 35. Kc1 { [%eval 11.15] } 35... Kd4 { [%eval 14.0] } 36. h6 { [%eval 10.32] } 36... Kc3 { [%eval 23.2] } 37. Nd5+ { [%eval 18.03] } 37... Kd4 { [%eval 60.87] } 38. h7 { [%eval 17.1] } 38... Kxe4 { [%eval 17.14] } 39. Nc3+ { [%eval 14.47] } { Black resigns. } 1-0

Stockfish 12 Released, 130 Elo Points Stronger

Stockfish 12 Released, 130 Elo Points Stronger

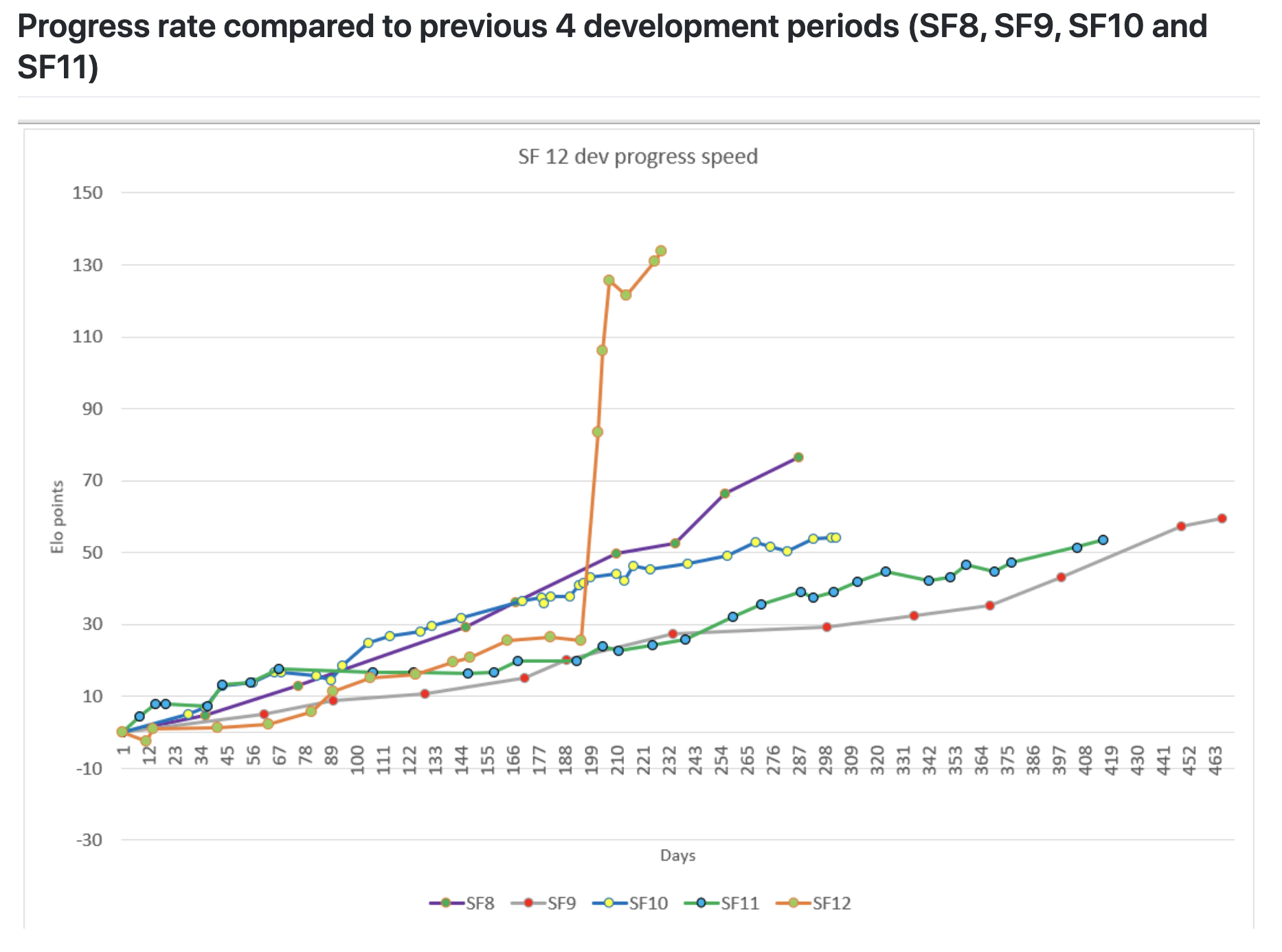

Version 12 of the popular open-source chess engine Stockfish was released on Thursday. It is a major update that includes an efficiently updatable neural network and is significantly stronger than earlier versions.

According to the official Stockfish blog, version 12 of Stockfish plays significantly stronger than any of its predecessors: "In a match against Stockfish 11, Stockfish 12 will typically win at least 10 times more game pairs than it loses."

The rating difference compared to Stockfish 11 is estimated to be about 130 Elo points. This became clear from internal progression tests during development and was recently confirmed In Chess.com's computer chess environment where Stockfish+NNUE and Leela Chess Zero performed quite comparably.

Stockfish 12 combines the brute-force computing approach of traditional Stockfish with the advanced evaluation capabilities of neural network chess engines such as AlphaZero and Leela Chess Zero.

In the new version, two evaluation functions are available. Besides the classical evaluation function, there is now the NNUE evaluation which is computed with a neural network based on basic inputs. The network is optimized and trained on the evaluations of millions of positions.

German Chess Magazine #1979

One early user wrote on Reddit: "From personal experience, Stockfish 12’s positional understanding is really unlike anything before it. Even Leela on extremely powerful hardware can seem blind to Stockfish 12’s search. Pretty much every major blindspot, like pawn structure weaknesses, seems gone in this new evaluation."

Stockfish 12 is available for download here with the neural network already embedded and ready to go. Chess.com expects to soon have Stockfish 12 available in our "max analysis" feature.

See also:

Friday, September 4, 2020

Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit

[Site "https://lichess.org/DmP4bcSE"]

[Date "2020.09.03"]

[White "Kung_Fu_Panda3"]

[Black "MoneyDoctor"]

[Result "0-1"]

[UTCDate "2020.09.03"]

[UTCTime "18:15:25"]

[WhiteElo "2433"]

[BlackElo "2018"]

[WhiteRatingDiff "-10"]

[BlackRatingDiff "+11"]

[Variant "Standard"]

[TimeControl "600+0"]

[ECO "A40"]

[Opening "Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit"]

[Termination "Normal"]

[Annotator "lichess.org"]

1. d4 e5?? { (0.00 → 1.57) Blunder. Nf6 was best. } (1... Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 d5 4. cxd5 exd5 5. Bf4 c6 6. Nc3) 2. dxe5 d6 { A40 Englund Gambit Complex: Hartlaub-Charlick Gambit } 3. Nf3 Bg4 4. Qd4 Qd7 5. Nc3?! { (1.27 → 0.69) Inaccuracy. exd6 was best. } (5. exd6 Nc6 6. Qe3+ Be6 7. dxc7 Nf6 8. Nc3 Qxc7 9. a3 Rd8 10. Qg5 Ng4 11. h3 Be7) 5... Nc6 6. Qe4 Bxf3 7. exf3 dxe5 8. Bb5 Nge7?! { (0.56 → 1.27) Inaccuracy. Bd6 was best. } (8... Bd6 9. Bxc6 Qxc6 10. Qxc6+ bxc6 11. Ne4 f5 12. Nd2 Nf6 13. Nc4 e4 14. fxe4 Nxe4 15. f3) 9. Be3 a6 10. Rd1 Qxd1+?? { (1.51 → 4.91) Blunder. Qe6 was best. } (10... Qe6 11. Ba4) 11. Kxd1 axb5 12. Nxb5 O-O-O+ 13. Ke2 f5 14. Qa4 f4?! { (4.52 → 6.90) Inaccuracy. Kb8 was best. } (14... Kb8) 15. Bc5? { (6.90 → 4.13) Mistake. Qa8+ was best. } (15. Qa8+ Kd7 16. Qxb7 fxe3 17. fxe3 g5 18. Rd1+ Ke6 19. Nxc7+ Kf6 20. Nd5+ Nxd5 21. Qxc6+ Rd6) 15... Nd5 16. Qa8+ Kd7 17. Qxb7?? { (4.21 → 0.85) Blunder. Qa3 was best. } (17. Qa3 Kc8 18. Bxf8 Rhxf8 19. Rd1 Nb6 20. Rxd8+ Rxd8 21. Na7+ Nxa7 22. Qxa7 Rd6 23. Qa3 Kb8) 17... Bxc5? { (0.85 → 2.35) Mistake. Rb8 was best. } (17... Rb8 18. Qa6) 18. Rd1 Bd4 19. Na7?? { (2.12 → -1.42) Blunder. Nxd4 was best. } (19. Nxd4) 19... Nce7 20. Qb5+ Ke6 21. Nc6 Nxc6 22. Qxc6+ Rd6 23. Qc4?! { (-1.34 → -2.45) Inaccuracy. Qb5 was best. } (23. Qb5 Rhd8 24. c4 Ne7 25. Qb3 Ra6 26. a4 Rda8 27. Qc2 Rxa4 28. Rxd4 exd4 29. Qe4+ Kf7) 23... Rb8 24. Rxd4 exd4 25. Qxd4?! { (-3.06 → -3.93) Inaccuracy. b3 was best. } (25. b3 Re8) 25... Rb4?? { (-3.93 → -0.44) Blunder. Kf7 was best. } (25... Kf7) 26. Qxg7 Nf6 27. b3?? { (-0.14 → -14.63) Blunder. Qxc7 was best. } (27. Qxc7) 27... Rbd4 28. g3 Rd1 { White resigns. } 0-1