- Login with Facebook to see what your friends are reading

- i

In January 2004, I called Magnus Carlsen the Mozart of Chess for the first time. It was a spontaneous, last-minute decision to meet a deadline for my column in the Washington Post. The name was picked up immediately and spread around quickly. It was used, misused, overused. Even the television network CBS could not resist the temptation last Sunday to compare the world's top-rated chess player to the famous Austrian composer. They titled a 60 Minutes segment on Magnus Carlsen "The Mozart of Chess."

The Spaniards took it a bit further in May 2007. Carlsen was supposed to fly to Valencia to play a simultaneous exhibition. At the same time, the film director Milos Forman was there, presenting a jazz opera, "A Walk Worthwhile." In 1985, Forman won one of his two Oscars for his movie Amadeus. It didn't take long to make the connection between the chess Mozart and the cinematic Amadeus. Forman and Carlsen met and played chess.

"Now I don't know what to do," said Amadeus after a few moves, hoping Carlsen might give him some advice. Mozart remained silent, but when Forman made a move, he said: "Not bad, not bad at all."

"At that moment," Forman later recalled, "I felt like I just won an Oscar." Encouraged, Amadeus pressed his luck and offered a draw. Carlsen politely declined and soon won the game.

Despite all the publicity the unassuming Carlsen didn't seem to be happy about being compared to Mozart. He was probably fed up with the name for some time and rightly so. I watched in horror as reporters stuck microphones in his face, asking: "How does it feel being called the Mozart of Chess?"

The moniker occurred to me when I was looking for a subhead for Magnus's great game against Sipke Ernst in Wijk aan Zee in 2004. It was a fresh, beautiful, imaginative masterpiece, created with lightness and ease, something Mozart might have composed in music at the age of six. Magnus was 13.

Carlsen,Magnus - Ernst,Sipke

Wijk aan Zee 2004

Wijk aan Zee 2004

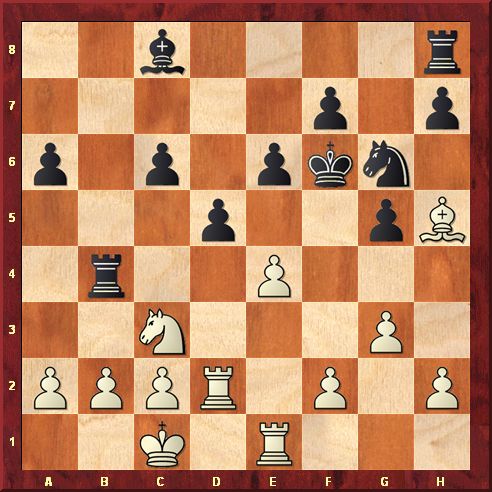

1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Bf5 (The Classical or Capablanca line in the Caro-Kann.) 5.Ng3 Bg6 6.h4 h6 7.Nf3 Nd7 8.h5 Bh7 9.Bd3 Bxd3 10.Qxd3 e6 11.Bf4 Ngf6 12.0-0-0 Be7 13.Ne4 Qa5 14.Kb1 0-0 15.Nxf6+ Nxf6 16.Ne5 Rad8

17.Qe2 (Magnus knew the queen move was endorsed by theoreticians, but he didn't remember the variations. He took 25 minutes to study the position.) 17...c5 (The fun begins now.)

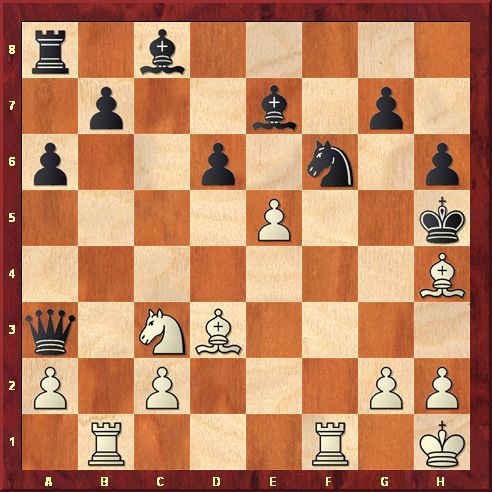

18.Ng6! (A similar knight sacrifice, but in a different position, was played in the game Bologand-Anand, Dortmund 2003, and Carlsen knew the game.)

18...fxg6? (Accepting the sacrifice loses. White penetrates through the weak light squares. Black would have been wiser to seek a slightly worse position after 18...Rfe8 19.Nxe7+ Rxe7 20.dxc5.)

19.Qxe6+ Kh8 20.hxg6 Ng8 (At a first glance black is protected from all threats, but white has a brilliant way to crash through. Also after 20...Rd7 a stunning rook sacrifice 21.Rxh6+!! leads to a mating attack after 21...gxh6 22.Bxh6 Rg8 23.Qf7 cxd4 24.Bg5 Qxg5 25.Rh1+ and white mates soon;

After 20...Rde8 21.Rxh6+!! gxh6 22.Bxh6 Rg8 23.Rh1 Rxg6 24.Bf8+ wins.)

After 20...Rde8 21.Rxh6+!! gxh6 22.Bxh6 Rg8 23.Rh1 Rxg6 24.Bf8+ wins.)

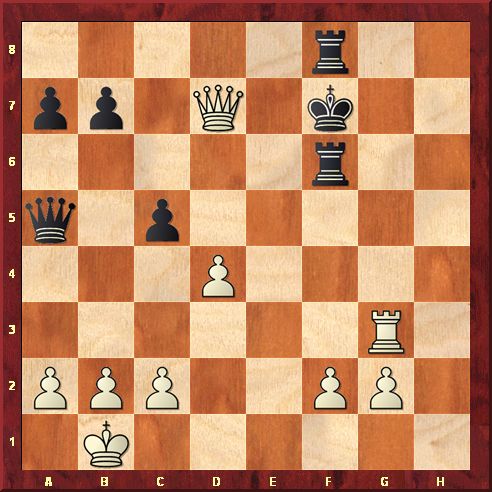

21.Bxh6! gxh6 22.Rxh6+!!

(This gorgeous rook sacrifice opens the h-file and is based on a vulnerable seventh rank.)

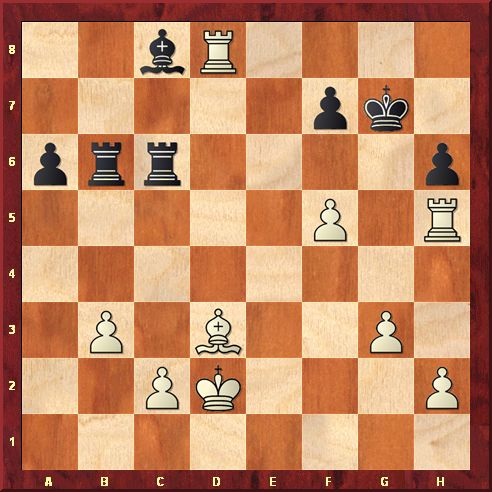

22...Nxh6 23.Qxe7 Nf7 (The only reasonable way to defend against 24.Qh7 mate.)

(This gorgeous rook sacrifice opens the h-file and is based on a vulnerable seventh rank.)

22...Nxh6 23.Qxe7 Nf7 (The only reasonable way to defend against 24.Qh7 mate.)

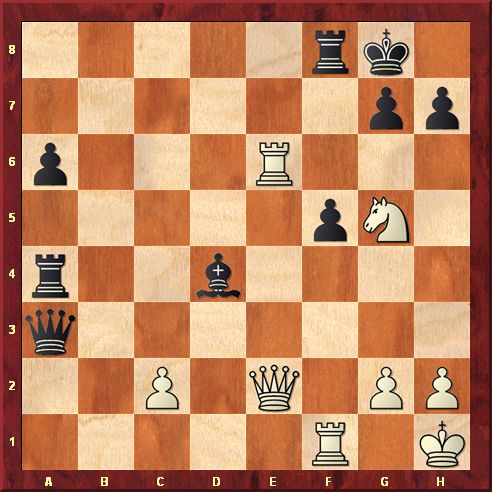

24.gxf7! (Creating a mating attack. Carlsen's move improves on the game Almagro Llanas - Gustafsson, Madrid 2003, in which after 24.Qf6+ Kg8 25.Rh1 Nh6 26.Qe7 Nf7 27.Qf6 Nh6 28.Qe7 Nf7 a draw was agreed.)

24...Kg7 (After 24...Qb6 25.Qe5+! Kh7 26.Rh1+ Qh6 27.Rxh6+ Kxh6 28.Qf6+ white wins, for example 28...Kh7 [28...Kh5 29.f3!] 29.c3! cxd4 30.g4 d3 31.g5 d2 32.Qh6 mate.)

25.Rd3 (A good way to win, but 25.Qe5+! Kxf7 26.Rd3 is better, for example: 26...Rxd4 27.Rf3+ Kg6 28.Rg3+ Kh6 29.Qg7+ Kh5 30.Qh7 mate; or 26...Rg8 27.Rf3+ Kg6 28.Qf6+ Kh5 29.Rh3+ Kg4 30.f3 mate.) 25...Rd6? (Allowing a nice mate. Black could have prolonged the game with 25...Qb6, but white should win after 26.Rg3+ Qg6 27.Rxg6+ Kxg6 28.d5.)

26.Rg3+ Rg6 27.Qe5+ Kxf7 (27...Kh7 28.Qh5+ Rh6 29.Qf5+ Kh8 30.Qe5+ Kh7 31.Qg7 mate.)28.Qf5+ Rf6 (After 28...Ke7 29.Re3+ wins. Now the game ends with an epaulette mate.) 29.Qd7 mate.

Bobby Fischer was also 13 when he was called the chess Mozart for his astonishing victory against Donald Byrne in 1956. Even long after he outlived his talent, Fischer considered it his best game. Carlsen's win over Ernst introduced him to the chess world. He still has plenty of time to create even better games. Garry Kasparov composed his signature game against Veselin Topalov in Wijk aan Zee in 1999 at the age of 35.

The brilliant American, Paul Morphy, who dominated the chess world in the late 1850s, was another chess Mozart. You can play over his marvelous victory against Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard de Vauvenargue in the Paris opera in 1858 to understand why. Morphy was 21 at that time, Carlsen is 21 now.

In CBS's 60 Minutes last Sunday, Bob Simon said: "You could not understand what Mozart did when he did it - it came from another world." Carlsen replied: "Was Mozart ever asked how he does this? I would be very impressed if he had a good answer to that. Because I think he would say - it just comes naturally to me, this is what I do."

Note that in the replay windows below you can click either on the arrows under the diagram or on the notation to follow the game.