Lubomir Kavalek

Huffington Post, October 31, 2010Chess World of Karpov and Kasparov

Standing next to each other, side by side, Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov made a last minute effort to sway the FIDE elections their way. One day before the vote, during the press conference in the Siberian town of Khanty-Mansyisk, they were trying to explain how they will change the chess world. Karpov was running for the FIDE presidency and Kasparov supported him. They still had a small chance to win. In the last six month they criscrossed the world, talking about the wonderful game of chess and what could be done to make it more popular. The next day, Sept. 29, the FIDE delegates re-elected Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, who promptly announced that he defeated two world champions. What happened?

In 1982, during the chess olympiad in the Swiss city of Lucerne, Florencio Campomanes bribed his way to the FIDE presidency and the World Chess Federation lost its innocence. The Icelandic grandmaster, Fridrik Olafsson, who was up for re-election could only say:"I haven't seen anything like it." Campomanes, a great manipulator known for his ornate speeches, turned the FIDE elections into farce. Money changed hands, threats were made and the delegates always voted his way. There is no doubt, he did many good things for chess, but he also ran FIDE slowly into bankruptcy.

In the past, Kasparov and Karpov were not standing on the sidelines and they usually took opposite sides during the FIDE presidential elections. There was a paradox: Kasparov fought Campomanes most of the time, but in 1994 in Moscow he helped to get him re-elected. Karpov, in turn, introduced Ilyumzhinov to FIDE a year later. Ilyumzhinov replaced Campomanes, but made him an honorary FIDE president. Last month, Karpov tried to defeat the man he initially brought in, but couldn't. Campo's legacy was too entrenched and the Kremlin leaders, noticing Kasparov on Karpov's side, threw their support behind Ilyumzhinov.

Watching Kasparov and Karpov fight together for a common goal was an unusual sight, not seen too often. Kasparov writes again about their rivalry in his book On Modern Chess, Part Four: Kasparov vs Karpov 1988-2009, recently published by Everyman Chess. During this period, the Grandmasters Association (GMA) was born and established itself with a high-level competition called the World Cup. Kasparov and his manager Andrew Page were interested in organizing it, but other grandmasters saw it as a conflict of interest and called me. I was appointed organizational director and later promoted to GMA's executive director. The World Cup, a series of six Grand Prix tournaments, was a very important competition and had to happen. "The first time in history that a tournament championship of leading chess players on the planet had been held," writes Kasparov. I signed contracts with six organizers within a few months and the World Cup was ready to go.

The centerpiece of Kasparov's absorbing book is his last world championship match against Karpov in 1990. Split into two cities, New York and Lyon in France, the match produced many dramatic moments. The highlight was the 16th game with 102 moves, the longest win in the history of the world championships. It lasted four days.

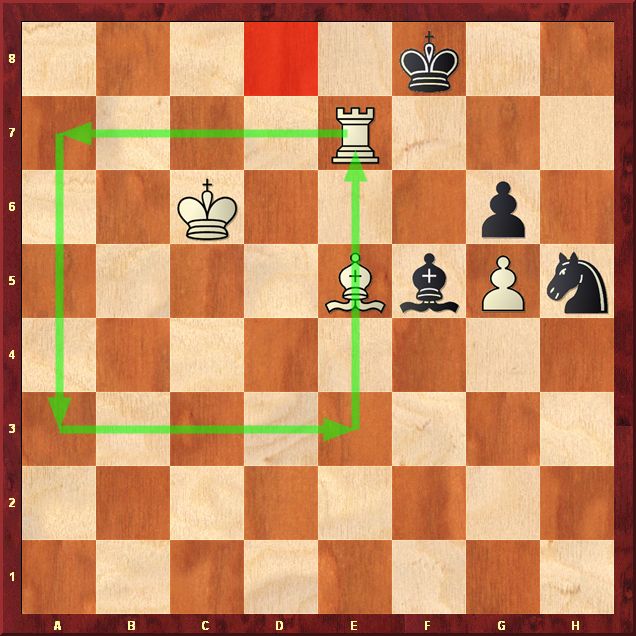

During this game I made a trip to Boris Spassky's house above Grenoble in the French Alps. When Boris picked me up at the Lyon airport, Kasparov just took a time-out. The adjourned position was tricky and even the best computers were unable to find a win for him. When we looked at it with Boris, we realized that the narrow path to victory lay in a mysterious square Kasparov's rook had to trace. The next day I flew to Barcelona and Boris showed the magical square to the spectators during the adjournment long before Kasparov could perform it on the chessboard.

To win the game, Kasparov has to walk his king to the (red) square d8. He can only do it by having his rook moving around a magical square.

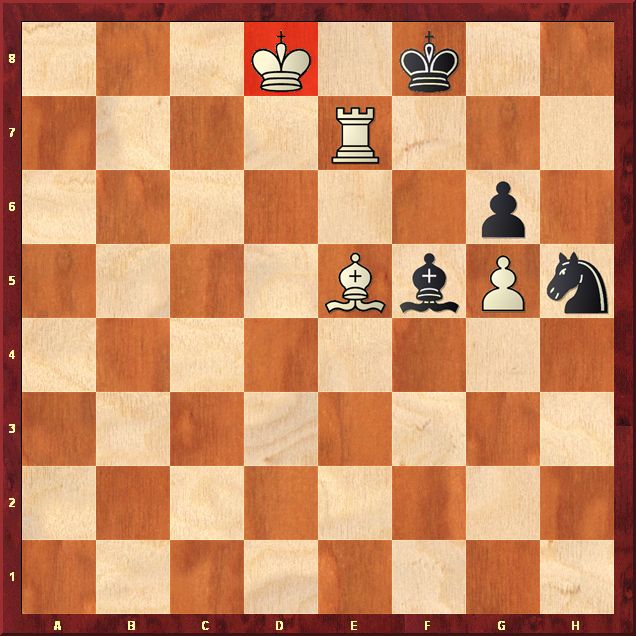

89.Ra7! (Drawing one side of the square.) 89...Bg4 90.Kd6 Bh3 91.Ra3! (The second side of the square is born. But why has the rook land on the square a3? It prevents the black knight from jumping to the square g3.) 91...Bg4 92.Re3! (The rook draws the third side of the square, preparing the white king's journey to d8.) 92...Bf5 93.Kc7 Kf7 94.Kd8 (The king's journey is over and white pushes the black king from the f-file.) 94...Bg4 95.Bb2! (Kasparov makes an important bishop move precisely in the moment when the black knight can't move. It opens the road for the rook to come back to the square e7.) 95...Be6 (After 95...Nf4 96.Re7+ Kf8 97.Ba3 black loses one of his pieces.) 96.Bc3! Bf5 (96...Nf4? is met by 97.Rf3 and white wins.) 97.Re7+ (Returning where it all began, the rook finishes the square journey.) 97...Kf8 98.Be5 (The domination is complete: the knight at the edge has no moves. White can easily force the black king to the corner.)

98...Bd3 99.Ra7 Be4 100.Rc7 (Kasparov is looking for a free square on the 8th rank for his rook. It was possible to play directly 100.Bd6+ Kg8 101.Ke7 Ng7 102.Be5 and white wins.) 100...Bb1 (After 100...Bf5 101.Bd6+ Kg8 102.Ke7 wins.) 101.Bd6+ Kg8 102.Ke7 (After 102...Ng7 103.Rc8+! Kh7 104.Be5 Nf5+ 105.Kf8 black has no defense against 106.Rc7+.) Karpov resigned.

Kasparov ends his book with the 2008 rapid and blitz match in the Spanish port of Valencia. It is a symbolic place where modern chess began: around the year 1485, the lazy, slow piece next to the king turned into a beautiful, fast-running, mad queen. And it was the place of the last duel between Karpov and Kasparov, their swan song.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

No comments:

Post a Comment