The Penguin gets zapped!

World of Chess , Issue 1507

Source: https://www.private-eye.co.uk/street-of-shame

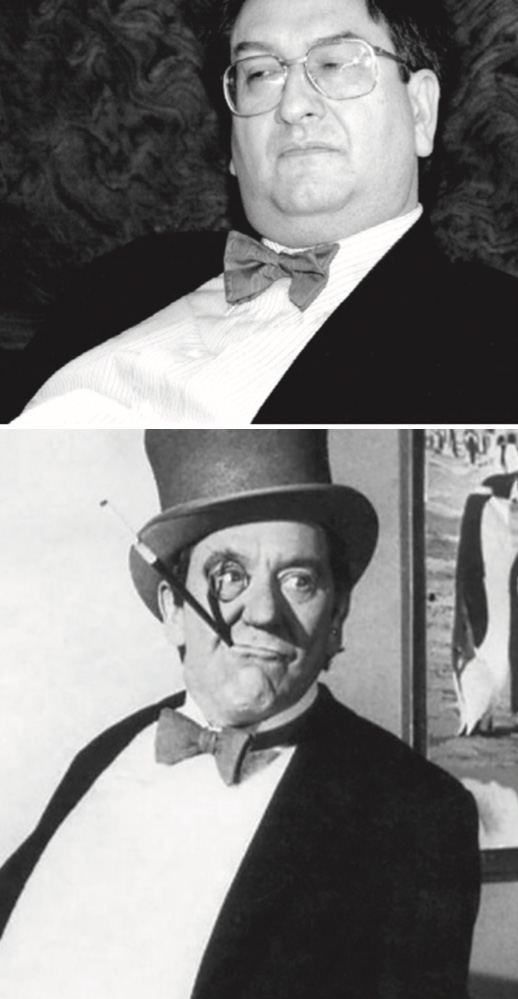

POW! BAM! Raymond Keene, aka The Penguin (er, top), finally gets zapped by the Spectator

Keene’s chess column in the Speccie two weeks ago had a brief postscript revealing that it was his last, after 42 years – though it omitted to say why he was going. As a Spectator source puts it, the Penguin’s offence was “keeping on plagiarising even after he’d been politely asked not to”.

The Eye has been exposing the Penguin’s bubonic plagiarism, in his books as well as his columns for the Spectator and the Times, for more than 25 years. In June 1993 (Eye 822) we reported that an entire chapter in his Complete Book of Gambits had been copied almost verbatim, without acknowledgement, from an article by American international master John Donaldson. The publisher had to pay Donaldson $3,000 and withdraw the chapter from the book, but the waddling word-stealer carried on regardless.

His most frequently pilfered source was Garry Kasparov’s My Great Predecessors (2003) – a book he looted so shamelessly he didn’t even bother to change its distinctive punctuation. Here is Kasparov on a 1954 world championship match: “At the most appropriate moment! By driving the knight from f6 the pawn spreads confusion in the black ranks.” And a 2009 Spectator column by Keene about the same game: “At the most appropriate moment! By driving the knight from f6 the pawn spreads confusion in the black ranks.”

Kleptomania

In 2013 Keene published his Little Book of Chess Secrets – which, as Eye 1357 showed, was largely cut-and-pasted from Kasparov’s My Great Predecessors. A 2013 Spectator column was also lifted from the Kasparov book (Eye 1343), reprinting its analysis of a 1923 game between Alekhine and Rubinstein but pretending it was Keene’s own. For good measure, the Penguin removed quotation marks and attribution in cases where Kasparov had quoted other greats, such as Bobby Fischer, thus presenting all the words as if they were his own.

Keene’s editors can’t pretend they were unaware of his kleptomania. In October 2008 the chess historian Edward Winter sent a letter by registered post and email to the Spectator’s then editor: “Dear Mr d’Ancona, May I advise you that over one third of the chess article by Mr Raymond Keene published on page 64 of The Spectator, 7 June 2008 was simply copied, word for word, from what I wrote some two years ago… Thank you very much in advance for informing me of your proposal for settling this matter.” Matthew d’Ancona never replied.

Grand larcenist

And how did the Penguin react? By, er, plagiarising another article by Edward Winter for a Spectator column a year later (Eye 1222), this time about chess coverage in the Guinness Book of Records. When challenged by online commenters, Keene affected astonishment. “All I can think of think of is that somewhere Winter’s comments may have been quoted without authorship or attribution,” he spluttered, “so I regarded them as being in the public domain.” Which prompted the question: did he seriously think it OK to pass off someone else’s article as his own so long as he didn’t know the author’s name?

In 2013 the chess blogger Justin Horton identified no fewer than 137 columns by the Penguin from the previous three years that included substantial passages stolen from books and articles by other authors. “How many more daylight robberies can he get away with,” we asked in Eye 1354, “before the editors of the Times and the Spectator call a halt to his criminal spree?” Six years on the Spectator has at last got the message, but Times editor John Witherow still seems unconcerned that his chess writer is a grand larcenist.

Having been caught red-handed so often, Keene does now occasionally acknowledge sources – though only fleetingly. Thus in the Times on Monday 7 October, analysing a 1962 game between Petrosian and Korchnoi, he said his notes were “based on” those in a book by Dutch grandmaster Jan Timman. But what does he mean by “based on”? Here is Keene’s assessment of Korchnoi’s fifth move: “Dubious. With reversed colours this set-up is fine as the king’s bishop has already been fianchettoed, although the line won’t yield any advantage. Here, however, the missing tempo makes itself painfully felt…” And here is Timman’s: “Dubious. With reversed colours this set-up is OK – since the king’s bishop has already been fianchettoed – although it won’t yield any advantage then. But the missing tempo makes itself painfully felt…”

For his Times column the next day, he turned to another Petrosian game from 1962, against Bobby Fischer. No mention of Timman’s book this time, but anyone familiar with it would have had severe déjà-vu all over again. Timman, for example, wrote that after 17 moves “White’s position is anything but healthy and in the text he manages to save his skin in an endgame that, with accurate play, he will just about be able to save.” Keene, by contrast, wrote that after 17 moves “White’s position is anything but healthy. The text is designed to head for an endgame that, with accurate play, he should just be able to save.”

Can the beleaguered Penguin save his skin at the Times? Tune in next week, same Bat-time, same Bat-channel.

No comments:

Post a Comment