International Chess Grandmaster

Huffington Post, December 2, 2010

Dragoljub Velimirovic used to be one of the world's most feared attackers, always looking for the impossible. His imaginative play was compared to the colorful world champion Mikhail Tal's razzle-dazzle. His playing style was unique, daring and often falling off the edge. He made risky moves and so many of them that you wondered how much punishment his chess pieces could take. He loved to create confusion on the chessboard, always believing he could find a beautiful escape from a bad situation. He had enough talent to pull it off, perhaps "too much talent " as Bobby Fischer once put it when we discussed the play of the Serbian grandmaster and champion.

At 68, Velimirovic doesn't seem to slow down. Still teasing and provoking, he took part in the Czech Coal Match in the spa resort of Marianske Lazne last month and was awarded a magnificent glass trophy for his entertaining play. He was a member of the veteran team that lost to the young ladies, the "Snowdrops," 14 to 18.

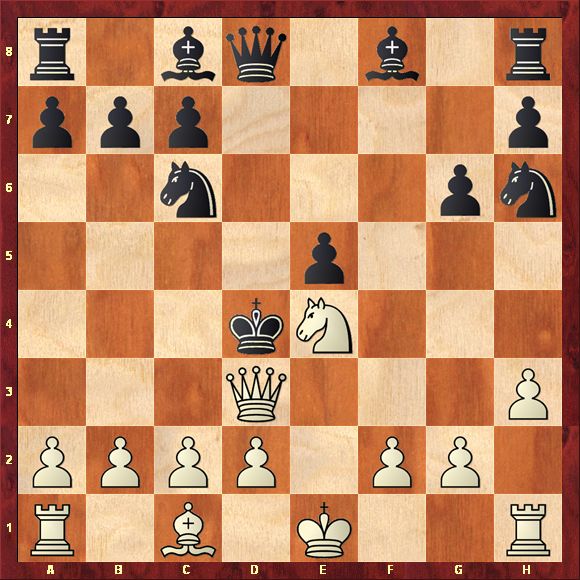

Velimirovic, who had opening lines named after him, always thrived on sharp play. For almost four decades, the Serbian grandmaster countered the Alekhine defense by charging his pawns forward as far and as quickly as they could go. They were like soldiers coming from the trenches in a big wave, huffing and puffing and dying one after another. He played the same way against the Lithuanian grandmaster Viktorija Cmilyte (pictured right), one of the world's top women players. When three from the Four Pawn Attack disappeared, Velimirovic used the last one to entomb the black king. Cmilyte refuted his reckless play with marvelous counterpunches and was expected to win. But in situations like that Velimirovic is always dangerous. Here is the dramatic game:

Velimirovic - Cmilyte

Veterans vs. Snowdrops, Marianske Lazne 2010

1.e4 Nf6 (It doesn't take much to provoke the Serbian grandmaster. Humpy Koneru played the Modern defense 1...g6 against him and Velimirovic immediately rammed it with 2.h4 d5 3.exd5 Qxd5 4.h5.)

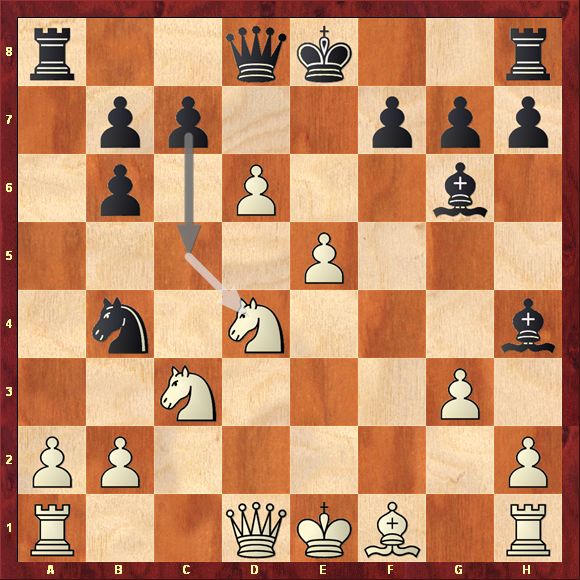

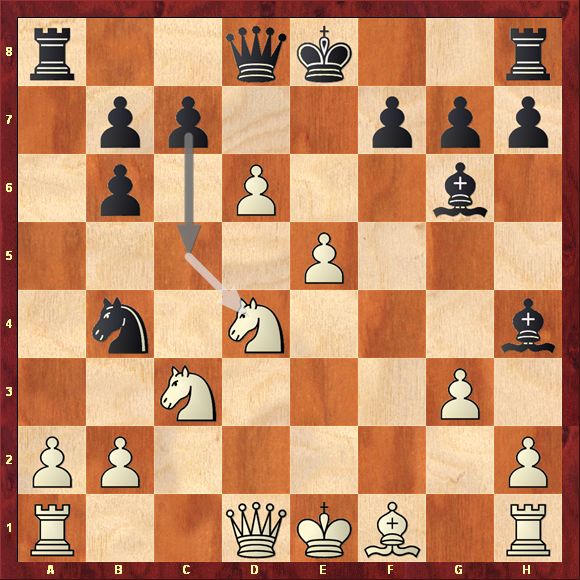

2.e5 Nd5 3.c4 Nb6 4.d4 d6 5.f4 (Velimirovic was always fond of the Four Pawn Attack, a messy, chaotic line that suites his style.) 5...dxe5 (Richard Reti's 5...g6 is advocated by Tim Taylor in his recent book Alekhine alert - a repertoire for Black against 1.e4, published by Everyman Chess.) 6.fxe5 Nc6 7.Be3 Bf5 8.Nc3 e6 9.Nf3 Be7 10.d5 exd5 (Nearly 40 years ago, Velimirovic encountered the immediate 10...Nb4 11.Rc1!? f6 [After 11...exd5 12.a3 c5 13.axb4 d4 14.Bxd4 cxd4 15.Nxd4 Qb8 16.Qe2 Be6 17.c5 Nd7 18.Rd1!? Nxe5 19.Nxe6 fxe6 20.Qh5+ g6 21.Qh3! black is in trouble.] 12.a3 Na6

13.g4! -a deflecting pawn sacrifice - 13...Bxg4 14.Rg1 f5 15.h3 Bxf3 16.Qxf3 0-0 17.Rc2 Qd7 18.Rd2 Rae8 19.d6 cxd6 20.Qh5 Rc8 21.c5 Rxc5 22.Bxc5 Nxc5 23.Rdg2 g5 24.Bb5 Qd8 25.b4 Ncd7 26.exd6 Bf6 27.Ne2 Ne5 28.Nf4 Qxd6 29.Rxg5+ Kh8 30.Qxh7+! Black resigned, Velimirovic,D (2490)-Gipslis,A (2580)/Havana 1971)

11.Bxb6?! (Interestingly, neither Taylor nor Valentin Bogdanov in Play the Alekhine, published last year by Gambit Publications, mentioned this move.

The main line is 11.cxd5 Nb4 12.Nd4 and now:

A. In one of the shortest games in this line, black played the faulty: 12...Bg6? 13.Bb5+ Kf8 14.0-0 Kg8 15.Nf5 [15.d6! cxd6 16.e6 with powerful pressure is even better.] 15...N4xd5? 16.Nxd5 Nxd5 17.Qxd5 c6 18.Qxd8+ 1-0 Holas,J-Sajtar,J/Podebrady 1956.

B. 12...Bd7! 13.e6?! [13.Qf3 is more solid .] 13...fxe6 14.dxe6 Bc6 15.Qg4 Bh4+ 16.g3 Bxh1 17.Bb5+ [The theory established 17.0-0-0 0-0 18.gxh4 Qf6 as the most popular line with roughly equal chances.] 17...c6 18.0-0-0 0-0 19.gxh4 h5 20.Qg3 cxb5 21.Bg5 Qb8 22.e7 Re8 [22...Nxa2+! 23.Nxa2 Rc8+ is stronger.] 23.Rxh1 Qxg3 24.hxg3 Rac8 25.Kb1 a6 26.Ne4 Rc7 27.Nf5 Nc8 28.Rc1 Rxc1+ 29.Kxc1 Nd5 30.Ned6 Nxd6 31.Nxd6 Rxe7 32.Bxe7 Nxe7 33.Kd2 b6 34.Ke3 g6 35.Kf4 Kg7 36.Kg5 Nd5 37.Ne8+ Kf7 38.Nd6+ Kg7 39.Ne8+ Kf7 40.Nd6+ Kg7 draw, Velimirovic,D (2500)-Kovacevic,V (2555)/Yugoslavia 1984)

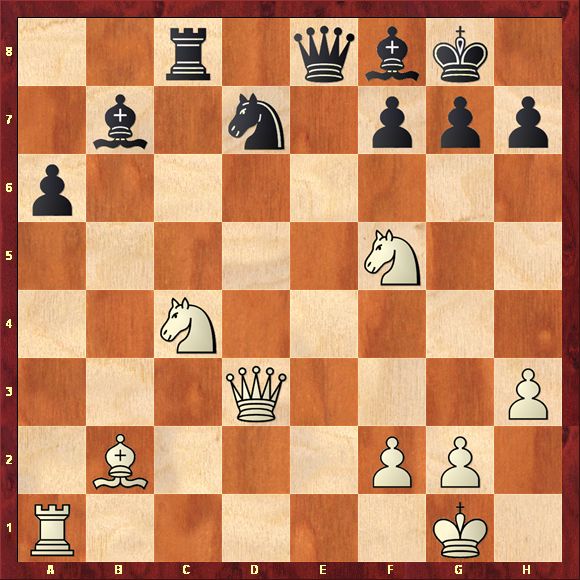

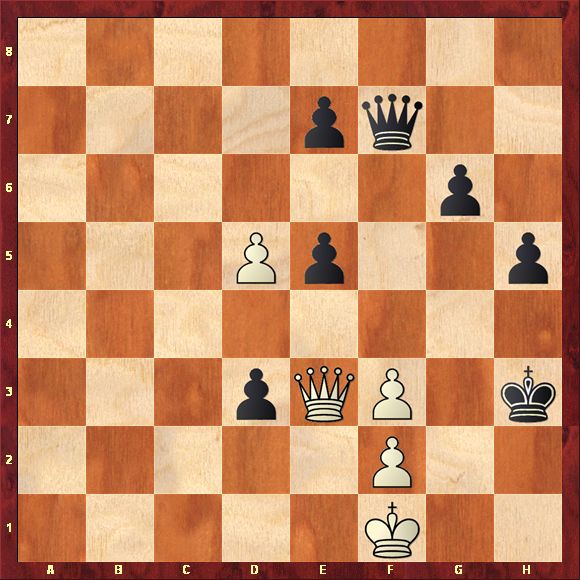

11...axb6 12.cxd5 Nb4 13.Nd4 Bg6 14.d6?! (Undeniably, Velimirovic's style - going after the black king. White creates a big mess, hoping that black trips somewhere. Objectively, it is too sharp. But after 14.Bb5+ c6! 15.dxc6 0-0! 16.cxb7 Rb8 17.Nc6 [After 17.0-0? Bc5! wins.] 17...Nxc6 18.Bxc6 Qc7 19.Bd5 Bc5 the white king still looks vulnerable.) 14...Bh4+ (Avoiding 14...cxd6? 15.Bb5+ Kf8 16.0-0 Kg8 17.e6 with white's big advantage.) 15.g3 (White is overextended and his king is in trouble.)

15...Qg5?! (Cmilyte probably got mixed up with the variation 15...0-0 16.a3 Qg5. Hiding the king is a good idea in general, but a great idea against Velimirovic. Anyway, after 15...0-0 16.a3 [Accepting the piece is disastrous: 16.gxh4? Qxh4+ 17.Ke2 Rfe8 18.Nf3 Rxe5+ 19.Nxe5 Bh5+ 20.Nf3 Re8+ 21.Kd2 Qf4 mate.] black has the following possibilities:

A. 16...Qg5 17.Kf2 [After 17.axb4 Bxg3+ 18.hxg3 Qxg3+ 19.Kd2 Qf4+ black has a draw at hand.] 17...Qxe5 18.Nf3 Qc5+ 19.Qd4 Qxd4+ 20.Nxd4 Bf6 21.Rd1 Nd3+ 22.Bxd3 Bxd4+ 23.Kg2 Bxc3 24.bxc3 cxd6 25.Bxg6 hxg6 26.Rxd6 Rxa3 27.Rxb6 Rd8 28.Rxb7 Rd2+ 29.Kh3 Rxc3 30.Rf1 f5 31.Ra1 Kh7 0-1 Carlsson,A-Kuehnrich,H/ICCF corr 1982

B. 16...c5 17.Nf3 Nc2+ 18.Kf2 Bg5 19.Bd3 Nxa1 20.Bxg6 hxg6 21.Qxa1 Bh6 22.Qa2 [22.Nd5! is better.] 22...Qd7 23.Qd5 Qf5 24.Re1 g5 25.Kg2 g4 26.Nh4 Qd7 27.Rf1 Rfe8 28.Nf5 Qc6 29.Ne7+ Rxe7 30.dxe7 Re8 31.Qxc6 bxc6 32.Na4 Rxe7 33.Nxb6 Rxe5 34.a4 Re4 35.a5 Rb4 36.Ra1 Rxb2+ 37.Kh1 Rb4 38.a6 1-0 Murey,J (2500)-Kovacevic,V (2560)/Hastings 1982)

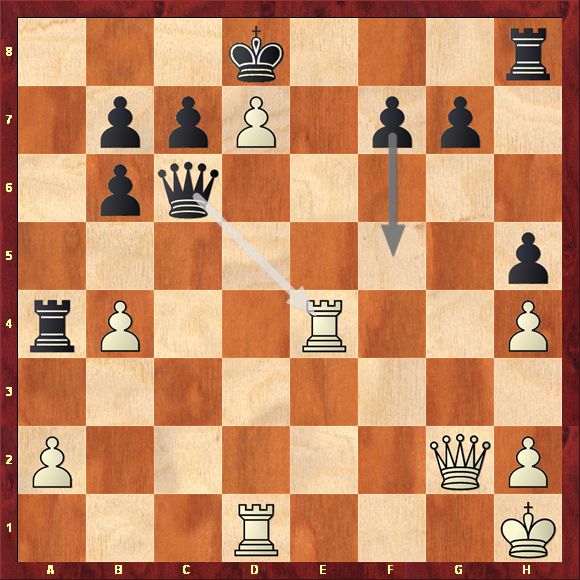

16.d7+? (Velimirovic makes sure the black king stays in the middle, but he could have prevented black's castling with: 16.Kf2! threatening to win a piece with 17.Nf3 and after 16...Qxe5 [After 16...0-0 17.Nf3 wins.] 17.gxh4 [or 17.Qg4 0-0 18.Qxh4] 17...0-0-0 18.Nf3 Qc5+ 19.Qd4 white has the edge.) 16...Kd8 17.Kf2 Qxe5 18.gxh4 Nd3+! (Destroying white's coordination, the knight leap leads to a winning position for black.)

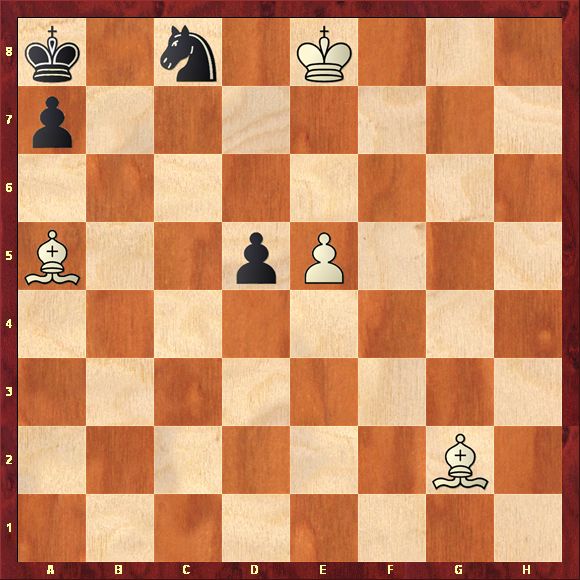

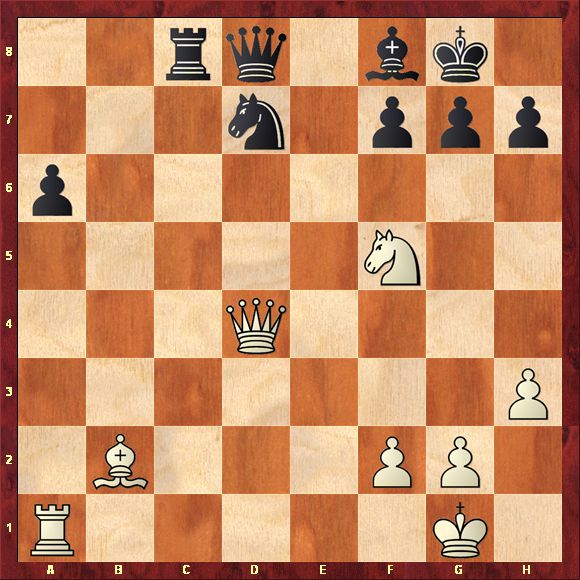

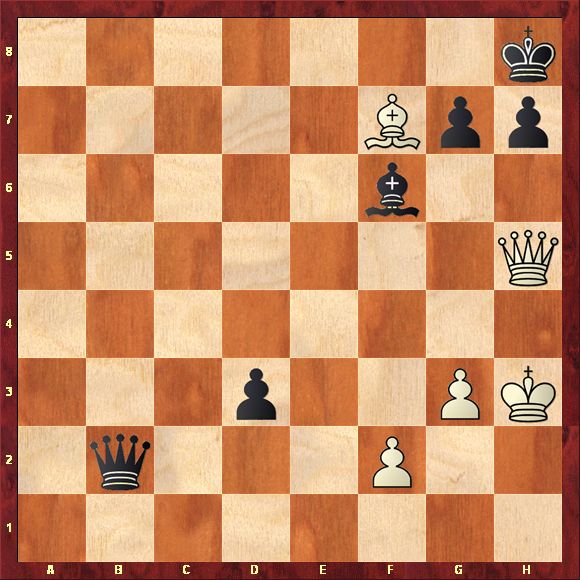

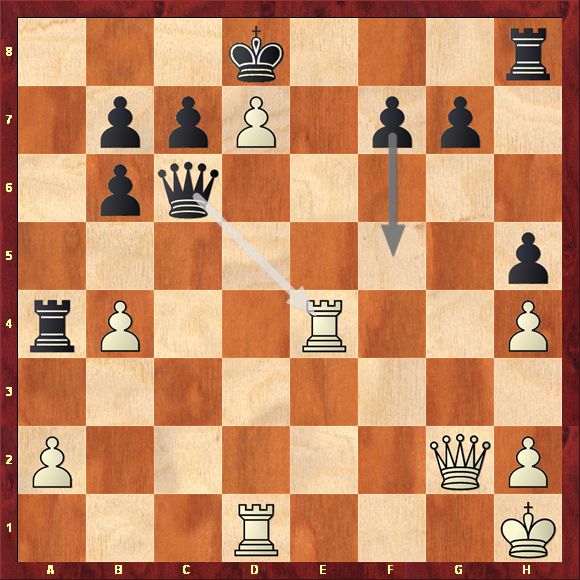

19.Bxd3 Qxd4+ 20.Kg2 (White can't protect the bishop. After 20.Ke2 Bh5+ wins. The game is virtually over, but for Velimirovic the fun only begins.) 20...Bxd3?! (A psychological slip. Velimirovic feels better with the queens on the board. Exchanging them with 20...Qxd3! wins comfortably, for example 21.Qxd3 Bxd3 22.Rad1 Bf5 and the d-pawn is doomed.) 21.Re1 h5 22.Kh1 Qd6 23.Qd2 Bc4 (Taking care of the d-pawn with 23...Bf5 was more advisable and better, for example 24.Qg5+ Qf6 25.Qxf6+ [25.Qg3 is met by 25...Qc6+ 26.Kg1 Qg6.] 25...gxf6 26.Nd5 Bxd7 27.Rad1 Bc6 and the pin wins it for black.) 24.Qg2 Qc6 25.Ne4 Bd5 (Computer engines come up with an elaborate, clever defense: 25...Rh6!? 26.Qxg7 Bd5 27.Qg5+ Kxd7 28.Rad1 Rd6 leading to a winning rook engdame: 29.Rxd5 Qxd5 30.Qxd5 Rxd5 31.Nf6+ Kd6 32.Nxd5 Kxd5 33.Re7 Kd6 34.Rxf7 Rxa2 and black wins.)

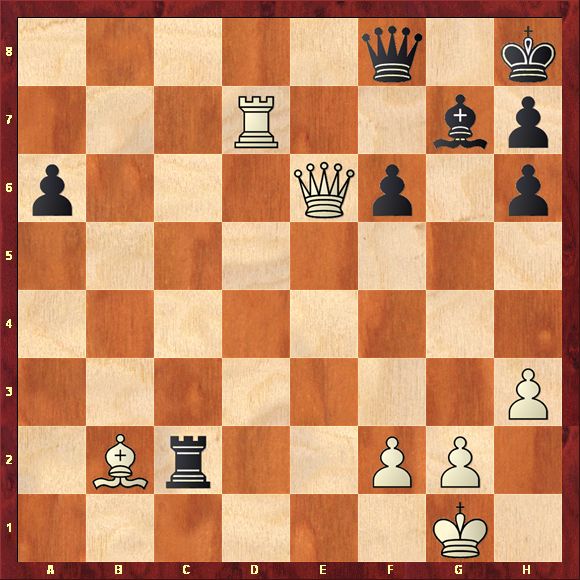

26.Rad1 Bxe4?! (Bringing the rook into play and protecting the bishop with 26...Ra5! left black with good winning chances, for example 27.b4 Bxe4 28.Rxe4 Rf5; or 27.Rd4 Bxe4 28.Rdxe4 [Black also wins after 28.Qxe4? Re5!; or after 28.Rexe4 Qc1+ 29.Qg1 Qxg1+ 30.Kxg1 Rxa2.] 28...Kxd7 29.Qxg7 Rd8! 30.Rd1+ Rd5 31.Qxf7+ Kc8 32.Rxd5 Rxd5 33.Qe8+ Qxe8 34.Rxe8+ Kd7 and the endgame is clearly in black's favor.) 27.Rxe4 Ra4?! (One square too far. 27...Ra5!? was still the best choice. It can transpose into previous note after 28.Rde1 Kxd7 29.Qxg7 Rd8 30.Rd1+ Rd5 31.Qxf7+ Kc8 etc.;

On the other hand, after 27...f5 28.Qg5+ Qf6 29.Qxh5! g6 (29...Rxh5? 30.Re8#) 30.Re8+ Rxe8 31.dxe8Q+ Kxe8 32.Re1+ Kf8 33.Qh6+ white should equalize.) 28.b4 (Keeping the black rook out of play.)

28...b5? (The game slips out of black's hands. It tends to happen in Velimirovic's games. When you thought you had him finished, he turned around and escaped. Still, black could have equalized after 28...f5! 29.Qg5+ Qf6 30.Qxh5 g6 31.Re8+ Rxe8 32.dxe8Q+ Kxe8 33.Re1+ Kf8 34.Qh6+ Kf7 35.Qh7+ Kf8 36.Qh6+ [or 36.Qxc7 Qc6+=] 36...Kf7=;

Cmilyte perhaps thought she could get away with 28...Rxa2, but white has two ways to refute it: A. 29.Qg5+ Qf6 [or 29...f6 30.Qg6!] 30.Qe3 Qc6 31.b5 wins.

B. 29.b5 Qc2 [29...Rxg2 30.bxc6 Ra2 31.cxb7 wins] 30.Qxc2 Rxc2 31.Ra4 Ke7 32.d8Q+ Rxd8 33.Re4+ wins.)

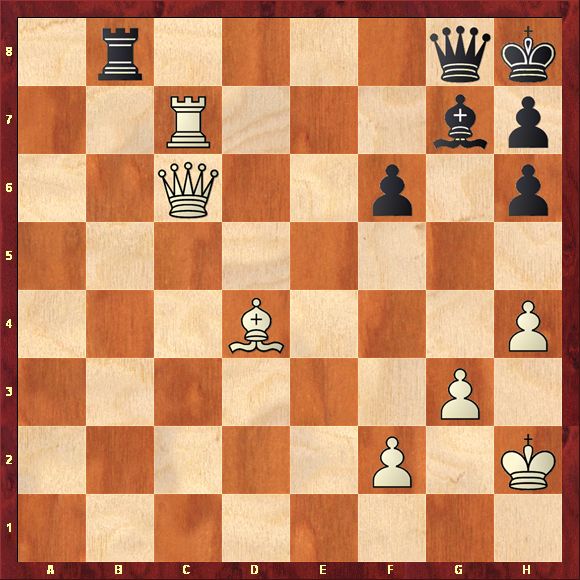

29.Qg5+ (White also wins after 29.Rde1 Kxd7 30.Qh3+! Kd8 31.Rd1+.) 29...Qf6 (After 29...f6 30.Qg6 threatening 31.Qe8+, wins for white.) 30.Qd5?! (The dance with the queen was unnecessary. White wins immediately with 30.Qe3! .) 30...Qc6 (30...Qd6 31.Qg5+ Qf6 32.Qe3 wins.) 31.Qe5 Qe6 32.Qd4 Qd6 33.Qg1 Qc6 34.Qg5+ Qf6 35.Qe3! (The white queen finally lands on the right square, threatening 36.Re8+.) 35...Qc6 36.Kg1 Qg6+ 37.Kf1 Qf5+ 38.Ke1 (Leaving black without good checks.) 38...Qxe4 39.Qxe4 Ra6 40.Qxb7 Black resigned.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

A Napoleon Forgery

The fighting defense 1.e4 Nf6 was named after the world champion Alexander Alekhine in the 1920s, although it appeared in the chess literature already at the beginning of the 19th century. Two recent books cover the opening well. In Play the Alekhine, Valentin Bogdanov uses his experience spanning more than three decades and concentrates on the main lines.

Tim Taylor's Alekhine alert offers a complete repertoire against 1.e4. Although he mentions the popular trends, his recommendations include mostly exciting offbeat lines. It is clear that he loved writing the book and could not resist including a story about a game that was allegedly played in Paris in 1802.

Madame de Remusat - Napoleon I

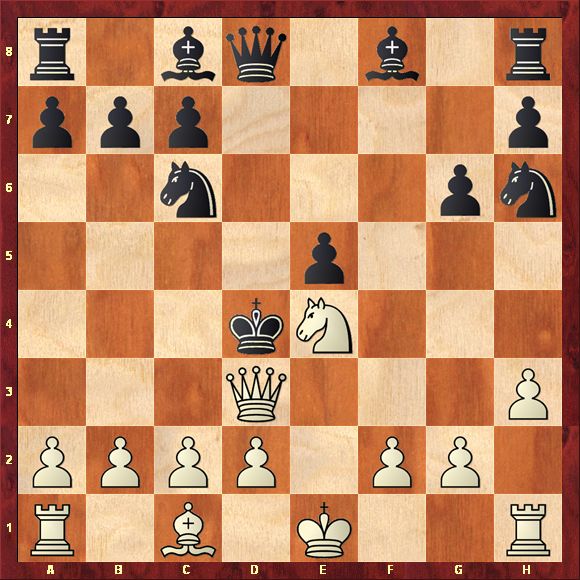

1.e4 Nf6 2.d3 Nc6 3.f4 e5 4.fxe5 Nxe5 5.Nc3 Nfg4? (5...d5!) 6.d4 Qh4+ 7.g3 Qf6 8.Nh3 (8.Bf4 wins) 8...Nf3+ 9.Ke2 Nxd4+ 10.Kd3 Ne5+ 11.Kxd4 Bc5+ 12.Kxc5 Qb6+ 13.Kd5 Qd6 mate.

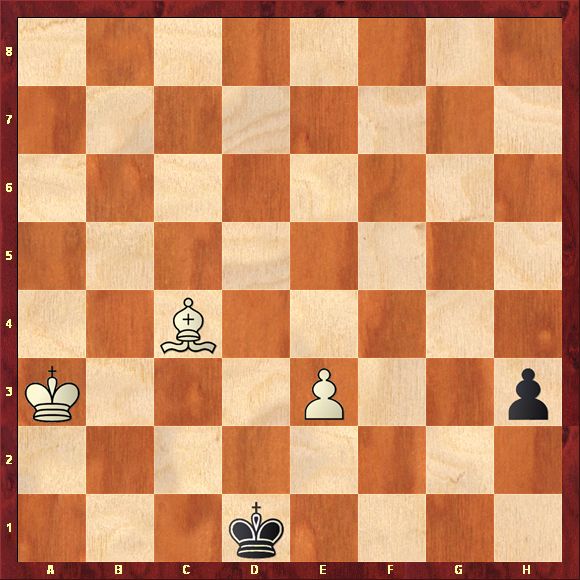

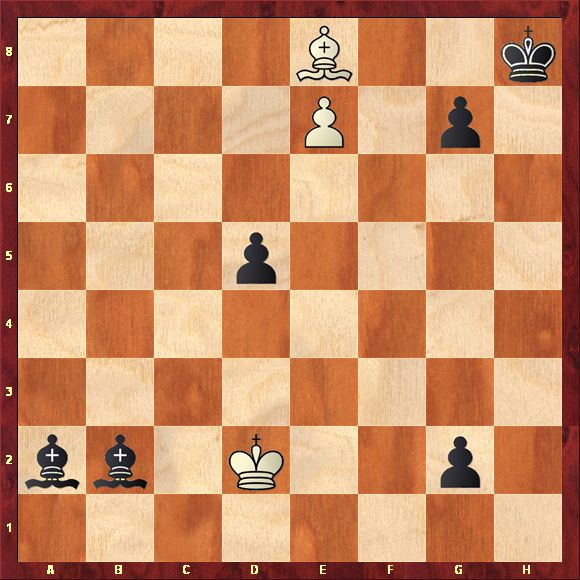

Had Taylor done his database research well, he could have found the same game with the same mate, but with reversed colors. I have added a few notes.

Napoleon I - Madame de Remusat

1.Nc3 e5 2.Nf3 d6 3.e4 f5 4.h3? (Digging trenches is not in Napoleon's style. The game switched to the Philidor defense, but Napoleon missed the near-refutation: 4.d4! fxe4 5.Nxe4 d5? 6.Neg5 h6 7.Nf7!! Kxf7 8.Nxe5+ and white should win.) 4...fxe4 5.Nxe4 Nc6 6.Nfg5? ("Accident, hazard, chance, whatever you choose to call it, a mystery to ordinary minds becomes a reality to superior men," de Remusat quoted Napoleon. The move drops a piece.) 6...d5 7.Qh5+ g6 8.Qf3 (Threatening 9.Qf7 mate.) 8...Nh6? (A turnaround. The emperor was on the verge of defeat: After 8...Bf5 black would win a knight. White wins now, hunting madame's king to mate.) 9.Nf6+ Ke7 10.Nxd5+ Kd6 11.Ne4+! Kxd5 12.Bc4+! Kxc4 13.Qb3+ Kd4 14.Qd3 mate.

This time Napoleon Bonaparte allegedly played the game in 1804 at Malmaison Chateau, where he resided with his wife Josephine. Napoleon's opponent, Madame de Remusat, was Josephine's "dame du palais" or lady-in-waiting. There is no doubt that the two played chess against each other. "He did not play well, and never would observe the correct moves," de Remusat disclosed in her Memoirs.

Both games were later revealed to be the creation of a clever hoaxer who has been fooling the chess world for some time.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

Photo of Viktorija Cmilyte by Vladimir Jagr