Lubomir Kavalek

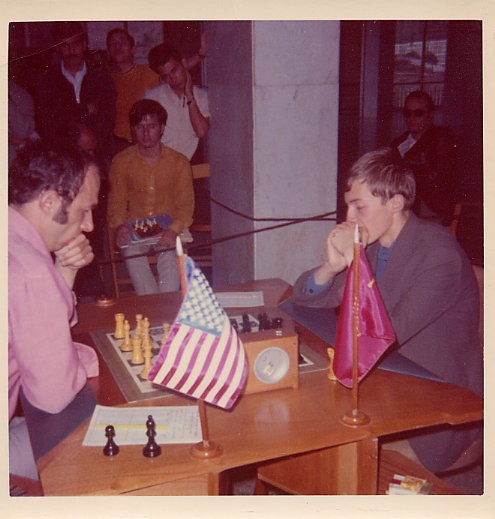

The Huffington Post, July 13, 2010One single square can make a big difference in a chess game. It helped me to launch one of my longest combinations against Anatoly Karpov in Caracas 40 years ago.

It was a memorable tournament for both of us. Karpov arrived in Venezuela as the reigning world junior champion. He played well enough in Caracas to become the world's youngest grandmaster at that time, at age 19, and his brilliant career began to take shape. In 1971 in Moscow, he clinched the first major tournament victory, sharing first place with the three-time Soviet champion Leonid Stein at the prestigious Alekhine Memorial tournament. In 1975 he was crowned the world champion. This year he may become the FIDE president.

I began the tournament in Caracas with the Czechoslovakian flag next to my chessboard, but in the middle of the event, at the United States Chess Federation's insistence, it was switched to the American flag. I started the "Presidente de la Republica" event as a Czech and won it as an American even before officially setting foot in my new adopted country. I arrived in New York one day after the tournament finished -- on July 13, 1970 -- exactly 40 years ago. My American journey began.

I would rate the victory in Caracas as one of my best tournament wins. I received a beautiful, tall presidential trophy for the 13-4 winning score. The organizers promised to send it to the USCF by mail, but it never arrived. Stein and Argentina's Oscar Panno, the former world junior champion and world championship candidate, shared second place with 12-5. Karpov tied for fourth place with two other world championship candidates, Borislav Ivkov of Yugoslavia and Paul Benko of the United States, scoring 11,5 - 5,5.

A few weeks after Caracas ended, Bobby Fischer dominated the tournament in Buenos Aires, scoring 15-2 and leaving his closest rival, the Soviet grandmaster Vladimir Tukmakov, 3,5 points behind. Things were looking good for America.

The combination against Karpov lasted nine moves. It was crafted from a popular Main line of the Spanish opening. The square d6 served as a landing platform for my pieces. They would leap into the heart of Karpov's position again and again. When the last one -- the white Queen -- landed there, Black's pieces were in a disarray. Totally dominated, Karpov was done, unable to defend his weaknesses.

Kavalek - Karpov

Spanish, Rubinstein Main Line

Caracas 1970

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.0-0 Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3 d6 8.c3 0-0 9.h3 Na5 10.Bc2 c5 11.d4 Qc7 (The Main line in the Spanish Opening.) 12.Nbd2 Nc6 (Akiba Rubinstein's move from the tournament in Ostende in 1907, where the players were called grandmasters for the first time. Black challenges the white center immediately.) 13.dxc5 (Efim's Bogolyubov's exchange from his 1924 game against Romanovsky was also fashionable in the 1970s. Today, the players return to Ossip Bernstein's move and grab the space with 13.d5. When the move first appeared in the game Bernstein-Rubinstein, Ostend 1907, Black created a beautiful defensive wall: 13...Nd8 14.Nf1 Ne8 15.a4 Rb8 16.axb5 axb5 17.g4 g6 18.Ng3 Ng7 19.Kh1 f6 20.Rg1 Nf7 21.Be3 Bd7 and the pieces, lined-up on the seventh rank, gave Black a lot of flexibility.) 13...dxc5 14.Nf1 (It is possible to regroup differently: 14.Nh2 Be6 15.Nf1 Rad8 16.Qf3, saving some time.) 14...Be6 15.Ne3 Rad8 16.Qe2 c4 17.Nf5 Rfe8 (Black is ready to take the knight on f5. The pawn sacrifice 17...Bxf5 18.exf5 h6!? is playable. Karpov knew about it but was probably more afraid of 19.Nd2!?, followed by 20.Ne4. Black has a good compensation after19.Nxe5 Nxe5 20.Qxe5 Bd6 21.Qe2 Rfe8 22.Be3 Nd5 23.Qf3 Nxe3 24.Rxe3 Rxe3 25.Qxe3 Bc5 26.Qe2 Qf4 as in Kavalek-Spassky, Solingen 1974.)

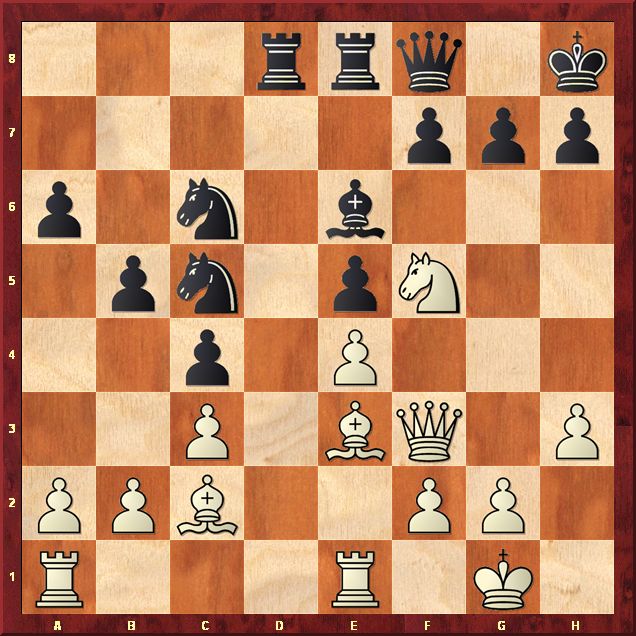

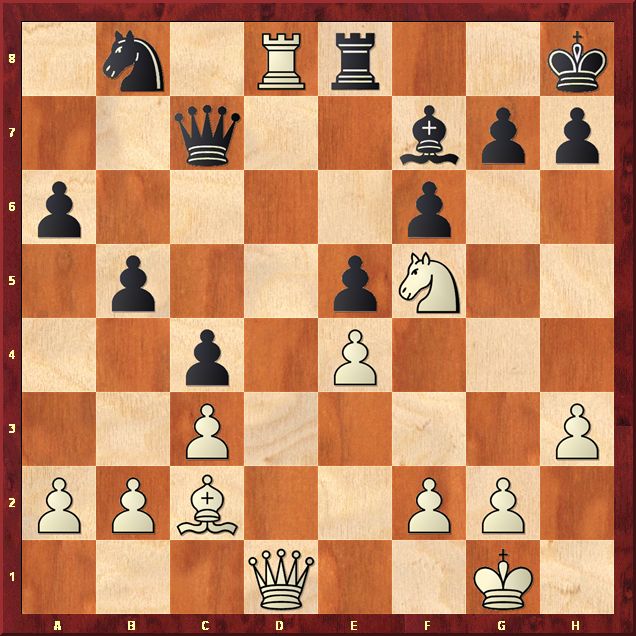

18.N3h4! (Another horse is anxious to land on the square f5. This move, taking care of Black's threat, was suggested by the Slovenian grandmaster and former world junior champion, Bruno Parma, who also played in Caracas. Parma was disillusioned with 18.Bg5, which was played by Bobby Fischer the same month, but a few thousand miles south in Buenos Aires. The game Fischer - O'Kelly continued: 18.Bg5 Nd7 19.Bxe7 Nxe7 20.Ng5 and here instead of 20...h6, Black should have blunted the attack with 20...Bxf5!? 21.exf5 h6.) 18...Kh8?! (Karpov's idea is to play 19...Ng8, followed by 20...Bxh4 and 21...Nge7, controlling the squares f5 and d5.) 19.Nxe7!? (Capturing the bishop and the dark squares. After 19.Bg5 comes 19...Ng8.) 19...Qxe7 (After 19...Nxe7 20.f4!? is possible.) 20.Qf3 Nd7 21.Nf5 Qf8 (The Queen plans to support the knight on the square c5 and help to cover the dark squares.) 22.Be3 Nc5? (A blunder that goes unpunished. The Yugoslav Encyklopedia of Chess Openings gave 22...f6 with the idea 23.Rad1 Nc5 and Black can answer 24.Rd6?! with 24...Nd3! 25.Bxd3 Rxd6 26.Nxd6 [26.Bc5? Rxd3! and black wins.] 26...Qxd6 27.Bc2 and White has a small advantage, but black can defend. But after 22...f6 White can transfer to the game with 23.Red1 Nc5 24.Rd6.)

23.Red1?! (I remember being preoccupied with my rooks: which one should go on the square d1? Just as I was playing this move, Leonid Stein, the three-time Soviet champion and tactician extraordinaire, walked by with a little devilish smile. It immediately dawned on me what I have done. The black Queen is overworked and can't be in two places at the same time. It allows a simple combination: 23.Nxg7! Kxg7 (23...Qxg7 24.Bxc5 wins a pawn.) 24.Bh6+! Kxh6 25.Qf6+ Kh5 26.g4++- Bxg4 27.hxg4+ Kxg4 28.Re3 and white mates soon. I tried to console myself with David Bronstein's wisdom that deep combinations are more exciting.) 23...f6

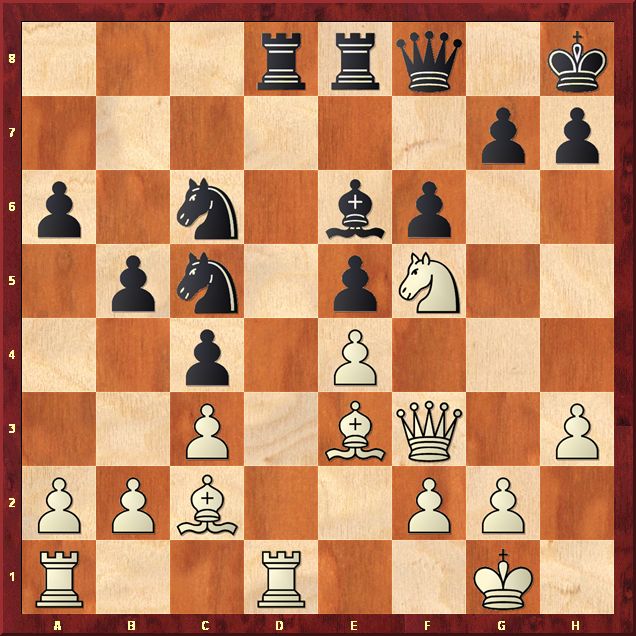

24.Rd6! (An opening salvo in one of my longest combinations, lasting nine moves. The square on d6 is being used again and again as a springboard for my pieces. It is the only way to get into Black's position. The Rook move destroys the coordination between the black pieces.)

24...Rxd6 (After 24...Nb3 25.Rxd8 Nxa1 26.Bc5 Qg8 27.Nh6! wins) 25.Bxc5 Rd1+ (After 25...Bxf5 26.exf5 White will soon have a powerful bishop on the square e4. ) 26.Rxd1 Qxc5 (Black seems to be fine, since 27.Qe3 is met by 27...Qxe3 28.Nxe3 Rd8 with equal chances.)

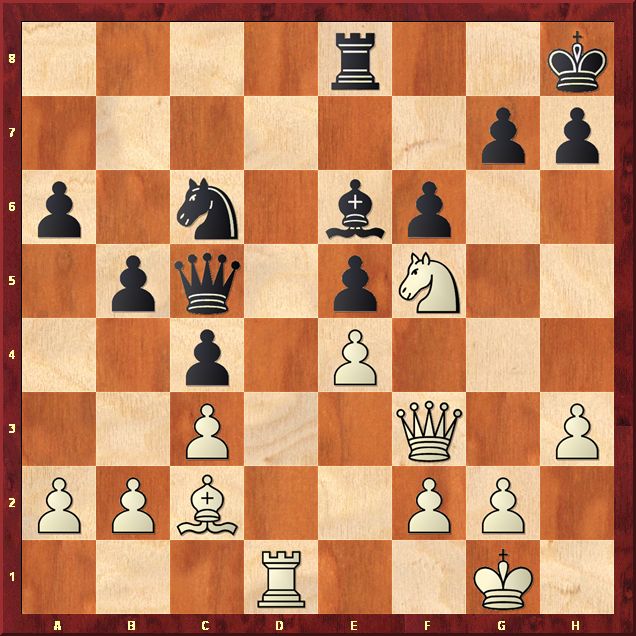

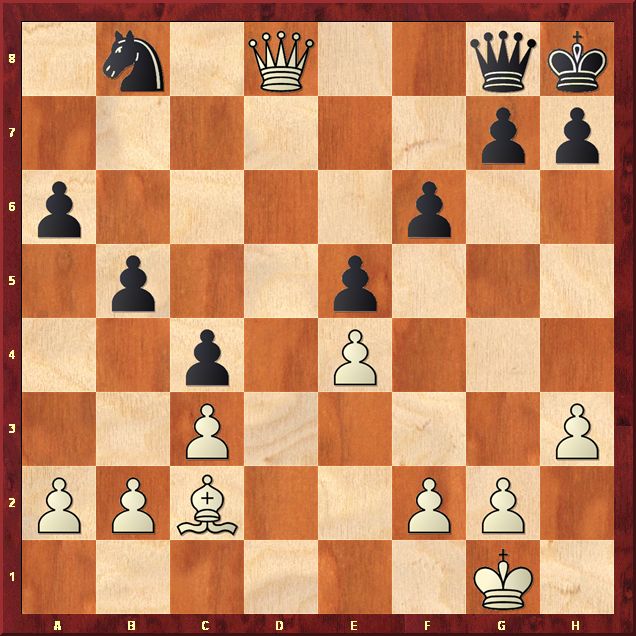

27.Rd6! (Twice the same move! Now it is with a greater effect, threatening 28.Qh5 g6 29.Qh4 g5 30.Qh6 winning.) 27...Bf7 (The only sensible move. After 27...g6 the stunning leap 28.Ne7!! decides. Black has no defense, e.g. 28...Rxe7 29.Qxf6+ Kg8 30.Rxe6 Rxe6 31.Qxe6+ Kg7 32.b4! White wins, for example 32...cxb3 33.Bxb3 Kh6 [or 33...a5 34.Bd5!] 34.Qf6 Qxc3 35.Qf8+ Kg5 36.h4+ and White mates soon. And after 27...Bxf5 28.Rd5! Qf8 29.exf5 the white bishop ends on the long diagonal h1-a8 with clear advantage.) 28.Qd1 (Securing the d-file.) 28...Nb8 29.Rd8 Qc7 (After the game Karpov told me that he had a better defense: 29...Qf8 and after 30.Nd6 Bh5. Now the queen sacrifice is tempting: 31.Nxe8 Bxd1 32.Bxd1 Nc6 33.Rc8 Ne7 34.Ra8 but after 34...Ng8 35.Bg4 Qe7 black can defend. Simpler is 31.Rxe8! Bxe8 32.b3 successfully breaking out on the queenside.)

30.Nd6! (Three times on the same square! White now simplifies into a winning endgame.) 30...Rxd8 31.Nxf7+ Qxf7 32.Qxd8+ Qg8 (The black Queen was forced off the middle.)

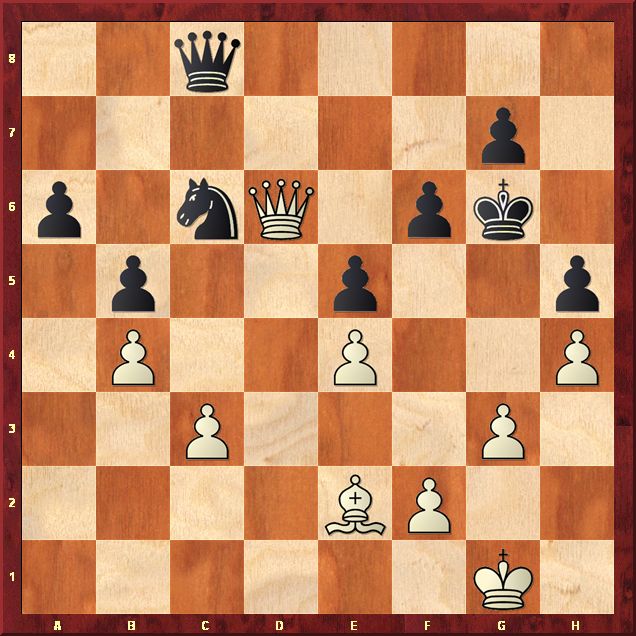

33.Qd6! (White's strongest piece leaps onto the celebrated square, dominating the black position and concluding the combination. Equally good was 33.Qc7 but it was too tempting to use the square d6 again.) 33...Qe8 34.Bd1! (Threatening to activate the bishop on the diagonal c8-h3 with 35.Bg4.) 34...h5 (Black prevents the threat, but the h-pawn becomes a target.) 35.Be2 Kh7 36.b3! (Creating more room for the bishop. The black queenside is weak, while the bishop controls both sides of the board.) 36...cxb3 37.axb3 Nc6 38.b4 Kh6 39.h4 Qc8 40.g3 Kg6?! (Making White's task easier, but even after 40...Nb8 41.Qe7 Qg8 [or 41...Qxc3 42.Qf8 Qe1+ 43.Bf1 Nd7 44.Qh8+ Kg6 45.Qe8+ Kh6 46.Qxd7 Qxb4 47.Qc6 wins.] 42.Kg2 Nc6 43.Qd7 Nd8 44.Qc8 Qa2 45.Bf3 Nf7 46.Qf5 White should win.)

41.Qd1! (White wins a pawn and the game is technically over. Black could have resigned, but he wanted to "talk" some more before saying goodbye.) 41...Kf7 (After 41...Qh8 42.Qd7! Nb8 43.Qf5+ wins.) 42.Bxh5+ Ke7 43.Bg4 Qc7 44.Qd5 Nd8 45.Bf5 Nf7 (After 45...Qxc3 46.Qd7+ ends it.) 46.Qe6+ Kf8 47.Qxa6 Nd6 (After 47...Qxc3 48.Qxb5 White should win.) 48.Qa8+ Ke7 49.Qg8 Nxf5 50.exf5 Qxc3 (Or 50...Kd6 51.Qe6 mate.) 51.Qxg7+ Kd6 (After 51...Ke8 52.Qxf6 wins.) 52.Qxf6+ Kd5 53.Qf7+ Ke4 54.Qb7+ Kxf5 55.Qxb5 Qe1+ 56.Kg2 Qe4+ 57.Kh2 Kg4 58.Qd7+ Kf3 59.Qd2 (A three pawn deficit is hard to overcome.) Black resigned.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

No comments:

Post a Comment