Pitching a Perfect Chess Game

Asked to name his best game, the legendary Bobby Fischer pointed to his encounter with Donald Byrne from the Rosenwald Trophy in New York in 1956, but admitted it wasn't perfect. "There is no perfect game in chess," he said. After all, we are human and we make mistakes. But according to the Hungarian writer and International Master Tibor Karolyi, Anatoly Karpov came close to playing a mistake-free game at the 1974 chess olympiad in Nice, France, and only a tiny error deprived him of creating a perfect game. It was played when we met on the top board of the USA-USSR match. It became one of Karpov's most analyzed games.

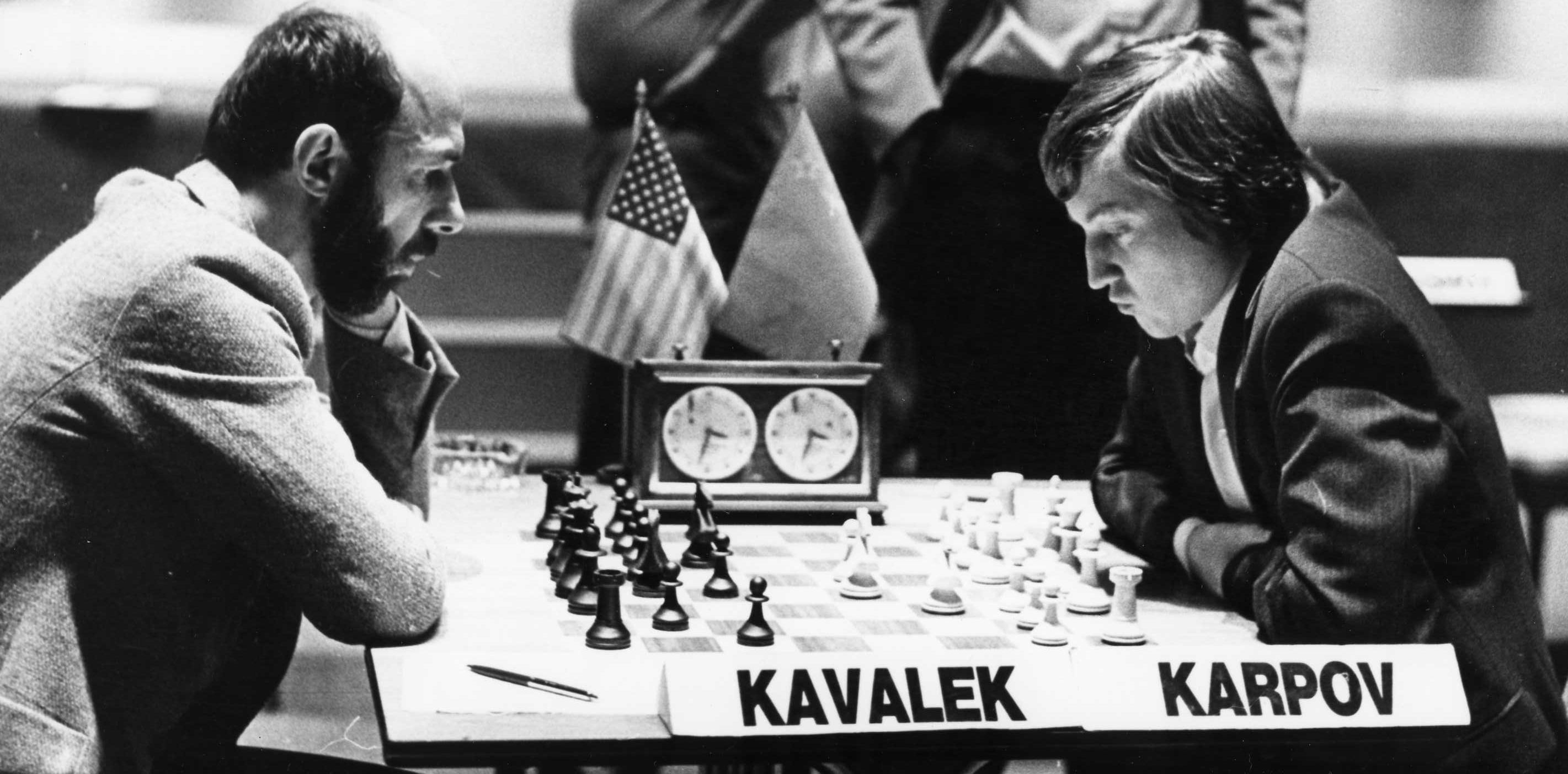

Of the 17 games we played against each other in major competitions in the span of 13 years (photo above is from Buenos Aires in 1980), Karpov won four games, I won once and we drew 12 games. My victory came in our first encounter in Caracas 1970 and we played our last game in Hannover, Germany, in 1983.

In his prime, the former world chess champion Karpov played like the famed FC Barcelona soccer team. Beautiful one-touch passes, allowing the Barca players to keep possession of the ball most of the time, were similar to Karpov's little chess moves that would deny his opponents the control of the game. He fought for every inch and giving him space was deadly. You can feel it from Karolyi's work, published by Quality Chess. The 560-page first volume Karpov's Strategic Wins 1 - The Making of a Champion covers years 1961-1985. The 576-page second volume Karpov's Strategic Wins 2 - The Prime Years embraces years 1986-2010.

Karolyi dissects Karpov's wins thoroughly and the books examine Karpov's career in detail. It was a colossal undertaking and Karloyi spent several years studying his protagonist. He delivers a fascinating account of Karpov's skills.

When I met Karpov in Nice, he was number two rated player in the world behind Fischer; I was number 10. It was the first time he played the top Soviet board and I felt the pressure with each of his moves. Still, I was able to keep his advantage to a minimum. The game was heavily analyzed, specially the concluding stage. Experts such as Mark Dvoretsky, Mihai Marin, Alexander Motylev, Karpov himself and others tried their hands in finding a logical conclusion. Karolyi devotes some 16 pages to it, showing most of the analysis and his improvements. He claims that Karpov made only one small inaccuracy. Was he pitching a perfect game?

This is hard to say because at a critical point I missed one move that could have saved me. True, I was pressed by time, but I should have found a pretty rook pin at the end of a logical sequence. The trouble was I had to move my rook backwards.

In the book "Invisible Chess Moves," Emmanuel Neiman and Yochanan Afek talk about the problem. "Forward moves are easier to find than backward moves, "they write. "Human beings usually walk forward, they seldom walk backward and hardly ever horizontally." In chess "we learn to move pawns (always forward) and to develop pieces toward the center and in the direction of opponent's pieces. There is a general movement from the back to the front, and some players are even reluctant to go backward on principle." It is an outstanding book, originally published in French and recently brought out in English byNew In Chess.

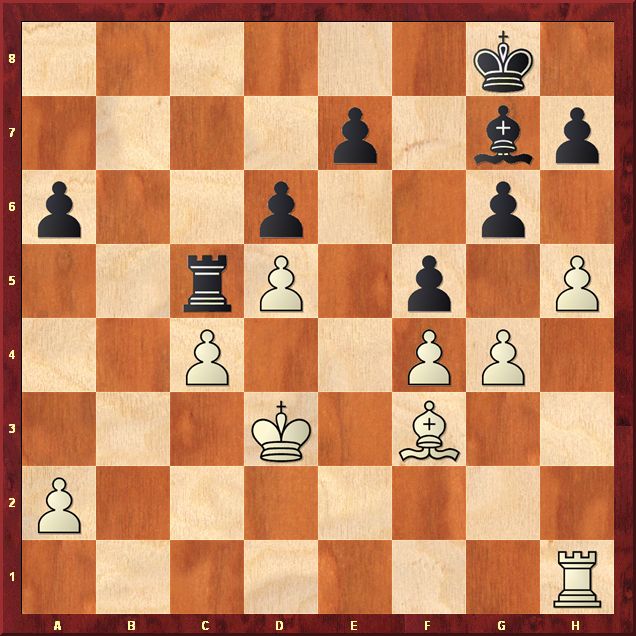

Let's see what happened in Nice. For the first 29 moves Karpov and I fought tooth and nail and we reached the following position:

White is better, but Black's game is solid and the bishops of opposite colors give it a drawing flavor. The only loose pawn on a6 can be protected easily. Karpov finds a way to improve his position and create winning chances.

30.h6 (Karpov is closing the kingside and fixes the pawn on h7. But how is he going to win it?) 30...Bf8(Keeping the pawn h6 under observation.) 31.Kc3 (Karolyi devotes six pages to 31.g5. The move locks the kingside completely, but it is not easy to envision how white could break through. Anyway, Karolyi shows the winning ways and concludes that white's king move is the only inaccuracy Karpov made during the entire game.) 31...fxg4 32.Bxg4 Kf7 33.Be6+ Kf6 34.Bg8 (White was able to dribble his bishop to g8, attacking the h-pawn. After 34.Kb4 a5+ 35.Kb3 Rc7 36.a3 g5 black is fine.) 34...Rc7 (Surprisingly, the computer engines suggest a pawn sacrifice as the way out. After 34...e6, for example:

a) 35.dxe6 Rh5=;

b) 35.Bxh7 exd5 36.Rg1 (36.Bg8 Bxh6! 37.Rxh6 Kg7) 36...Rxc4+ 37.Kd3 Rxf4 38.Rxg6+ Kf7 the white pieces stumble against each other.;

c) 35.Bxe6 a5 36.Kb3 Rc7 37.Ka4 Rxc4+ 38.Kxa5 white still has some chances after 38...Rxf4? 39.a4 the passed a-pawn is dangerous, but black should play 38...Be7 to keep the a-pawn in check.) 35.Bxh7 e6 36.Bg8 exd5 37.h7

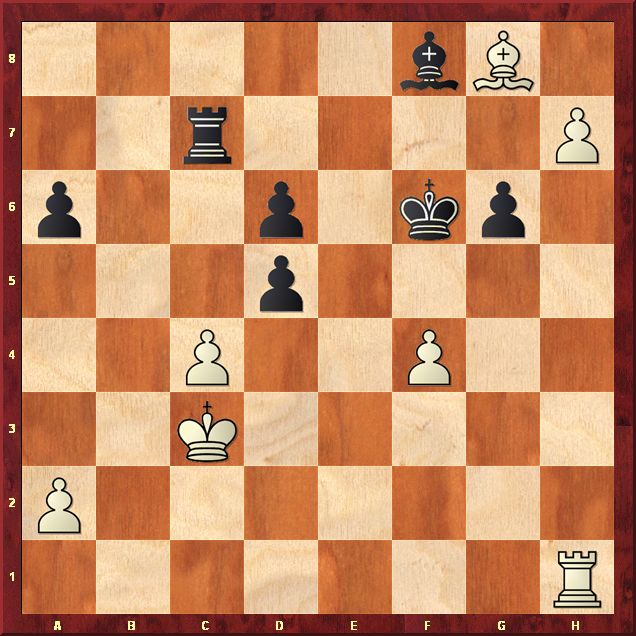

37...Bg7? (A time pressure blunder. The correct 37...Rxc4+! gives black good drawing chances, for example

a) 38.Kd3 Bg7 39.h8Q?! [39.Bxd5!? would be the only try to win, but after 39...Rc5 40.Ke4 Bh8 41.Rg1 Rb5 black has some chances to hold.] 39...Bxh8 40.Rxh8 and I missed the backward rook move 40...Rc8! threatening 41...Kg7, black draws. But not 40...Kg7? 41.Bxd5 Rc5 42.Rg8+ Kh7 43.Be6 wins as I calculated, abandoning the idea.

b) Better seems 38.Kb3 Bg7 39.Bxd5 Rc8 40.Be4 threatening 41.Rg1 with some pressure.)

38.Bxd5 Bh8 39.Kd3 Kf5 40.Ke3 Re7+ 41.Kf3 a5 42.a4 Rc7 43.Be4+ Kf6 44.Rh6 Rg7(Unfortunately, 44...Kg7 45.Rxg6+ Kxh7 46.Rg1+ Kh6 47.Rh1+ Kg7 48.Rh7+ drops a rook.) 45.Kg4(Black is in zugzwang and must lose the pawn on g6.) Black resigned.

No comments:

Post a Comment